Andrew Duncan’s Torana was never meant to be the supercharged in-your-face machine that it is now, but sometimes things work out for the best!

Words: Todd Wylie Photos: Rodd Dunn

Owning his first Torana at age 16, it should have been a given that Andrew Duncan would end up owning more than just one. Adding to the high likelihood of his passion are the facts that he was born and raised in Gore, where owning tough cars is a rite of passage, and his older brother was always building, modifying, and messing with tough cars and hot rods. As life moved on, he ended up moving away from Gore and away from the old car scene, but memories of that first 173-powered LJ have stuck with him the entire time.

Finally, when he was living in a new house with a shed big enough to tinker in, he decided that the time was right. Plenty of peer pressure from workmates aided the cause, as did a good mate, Peter, taking the plunge back into the car world around the same time. Owning another Torana would be a stark departure from the swathe of Japanese cars that Andrew had been used to driving in the interim — but it was just the challenge he was up for.

With the benefit of hindsight, he realises he may have got himself much more of a challenge than he probably needed to. That’s often the way, though, when purchasing cars from the other end of the country, sight unseen. The story that Andrew was told by the seller is a familiar one, about how the car had just got a WOF and was as solid as a rock. He couldn’t be home when the transporter dropped off his new purchase, but when he came up the driveway to find the car there with blocks of wood stopping it from rolling down the road, he knew straight away he was in for trouble. Things only got worse when he opened the door to find it full of water. Sure, the car had been delayed and spent a few weeks in the trucking yard while waiting for a ferry crossing, but this was next level.

Although the handbrake didn’t work and the transmission’s park setting wasn’t strong enough to hold the car, he hopped in and took it around the block to get more of a feel for it. A quick check to see if it could pull a skid proved that it could, and the grin on his face was exactly as he’d hoped it would be. Sure, it would need new wheels, a new interior, and a bit of love, but nothing he hadn’t dealt with before, he thought … then he found the rust. Lurking under thick layers of tar, sound deadening, and bog was plenty of metallic cancer. Not just surface rust either; the car had fractures in the floor pans, sections missing out of the subframe, and no metal left behind the rear outer sill.

“It was completely Swiss cheese with mud worms filling inside panels,” recalls Andrew. “I was gutted to say the least!”

Further inspection resulted in the rear brake shoes falling on the floor when the drums were removed — so at least the mystery of the non-working handbrake was easily solved. Not that this would matter for some time, as the car clearly needed much more work than just the brakes attended to. While it could have easily spelled the end of the dream for Andrew, he was determined that he wouldn’t be beaten quite that easily, and instead of letting it get him down, he saw it as an opportunity to make the car even better.

It would be four-and-a-half years before it would hit the road again, but when it finally did, the car would re-emerge as a completely different machine, and Andrew would emerge with plenty of new skills. Being hands-on with machinery from his experience in the viticulture industry, he made the decision early on in the piece to try to do as much of the rebuilding as he could himself. Prior to this, he’d never really done much welding, and certainly no bodywork or real fabrication. It was definitely going to be a challenge, but it would be one that he embraced.

“I took to learning as I went. I had to figure out how to not blow huge holes in panels with the MIG and learned how much of a friend an angle grinder can be,” he laughs.

While he did turn to the professionals when it came to the structural repairs he required, he credits Discovery Channel and the internet for teaching him enough to get the rest of it sorted.

During the build, the 327 and Powerglide that had come with the car were removed as the body was stripped back to a bare shell. The plan was to give the small block a freshen-up, but the more he looked at it, the more it was showing not to be worthwhile. A look on Trade Me uncovered just the thing — a brand new short block that had been set up for forced induction. While a supercharger had never really been on the cards from the outset, now it seemed wrong not to. The driving force for this, if you’ll excuse the pun, was that Andrew and his brother had always talked about building a blown Torana. So now, despite his brother having passed away 10 years earlier, things were finally falling into place to make it all happen.

The blower itself was purchased from the US, as were the twin 650cfm boost-referenced carbs and many other parts. Marlborough Engine Reconditioners was called on to assemble the engine with a set of Dart Pro1 heads filled with Crane Cams rocker gear. Before Andrew could set up the rest of the combo, a Weiand intake manifold was fitted to join the engine and supercharger together. Having come so far, Andrew knew there was no point in cutting corners now, so he went to town ordering a swathe of MSD ignition components. It was money well spent too, as, thanks to a 8.5:1 compression ratio, the blower could be set up with nine-per-cent under-drive to create 10 pounds of boost.

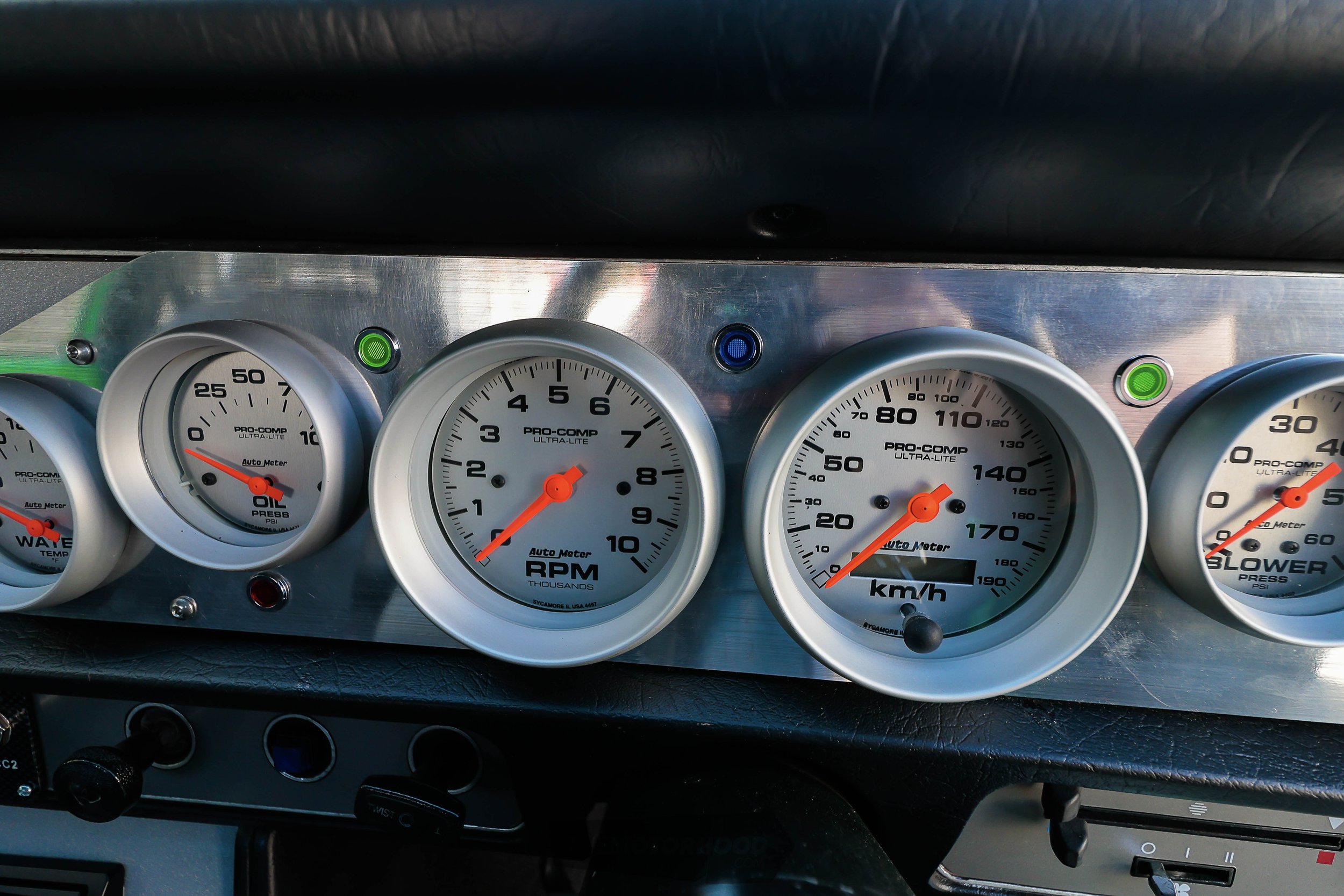

As with the original engine, the Powerglide would never make it back into the car. Instead, it was replaced with aGM TH350 that had been rebuilt by Automan Automatics complete with a 2500rpm stall converter. The nine-inch diff, on the other hand, would be refitted, but not until Dave Sales from Jalopy Engineering had worked his magic on it, rebuilding it with a Truetrac centre and disc brakes. With all the new-found power, the front brakes — even though they actually had worked to begin with — were also wisely replaced with Wilwood calipers and discs. A Wilwood master cylinder and Wilwood proportioning valve were added to finish off the package. Interestingly, the calipers were mounted to HQ spindles rather than to the stock Torana ones.

Helping to bring the ride height down from factory settings is now a set of King springs wrapped around Monroe GT shocks, while a hoard of Nolathane bushes and boxed trailing arms help to give a better, more consistent ride.

By this stage, the engine bay had been smoothed off and the rust removed from the body. The whole thing was then resprayed in Spitfire Green — a colour usually found on VE Commodores. Murf’s Metalworx was responsible for the finer details on the body before laying on the paint. In very stark contrast to the in-your-face colour is a set of black 15×7-inch and 15×10-inch Convo Street Pro II wheels wrapped in 215/60R15 and 295/50R15 tyres. The SLR 5000–style flares were very much a necessity to fit the big tyres, and Andrew wisely chose to fit front and rear spoilers to complete the tough look.

Elliot Sutherland from Classic Automotive and Transmission was called on to help get the engine running and tuned, along with sorting out the programmable ignition system and any other teething issues. As it stands, the car’s just been run in and is starting to get a few kilometres on the clock. The build has been a massive learning exercise, but an experience that Andrew’s loved. Adding to that enjoyment the last few years has been Andrew’s third grandchild, Theodore, who’s been as involved as a three-year-old can be, and since the car has been on the road, he’s been in it more than anyone else.

We can only imagine that growing up with a grandad like this, that there’s set to be another generation of Torana lovers in the future. Here’s hoping they take the time to pick up as many of Grandad’s new-found skills as possible, not to mention learn to drive it for when he’s ready to hand over the keys!

This article originally appeared in NZV8 issue No. 194