Take a look into the high-speed and ever-changing journey of a normal working bloke, who has achieved great things and packed five lifetimes into one as a result of determination, working his arse off, and making the most of a natural, instinctive and intuitive gift for anything mechanical. And he’s a long way from finished yet…

GIFTED, OBSESSIVE, DIFFERENT

By the time he was 10, Grant Rivers had already shown that he possessed an astonishing gift for mechanical things, never more apparent than when — entirely unaided in either thought or deed — he fitted his dad’s Villiers lawnmower engine onto his bicycle. He’d owned motorcycles and cars before he was old enough to hold a driver’s license, and owned his first V8 road car at age 16. Another decade on, he’d topped his polytech class three years in a row and had become an A-grade motor mechanic, had owned a string of American cars, was building performance V8 engines, and had completed two major car-builds in his mum and dad’s single garage and backyard.

Grant Rivers and I lived in the same town, we were the same age, and we were both heavily immersed in American and Australian cars, so it was inevitable that our paths would cross early on. We met as 18-year-old kids, became good mates, and our close friendship has spanned 40 years. There were a bunch of us who were heavily into cars as teenagers in Whanganui, but, even back then, it was obvious that there was something different about Grant’s interest — no, obsession — with cars compared with the rest of us. His focus was less divided. He was less easily distracted. He’d often be in his garage late on Friday and Saturday nights while the rest of us did road-trips, partied, and chased skirt. On week nights, he had the energy to work on his cars until two in the morning while the rest of us were done by 10 or 12. Looking back, I didn’t realize then that he was going to be such a man on a mission, but I should have — all the signs were there to see, as plain as could be.

By 1985, Grant — or ‘Grub’ as he was known by then — had married Fiona (I was his best man), they’d bought their first house, and the ‘Life in the Fast Lane’ Falcon had been sold to pay for the build of a large garage in their spacious backyard. But there was, of course, an automotive void that had to be filled — both quickly and cheaply.

MARRIED WITH CHILDREN

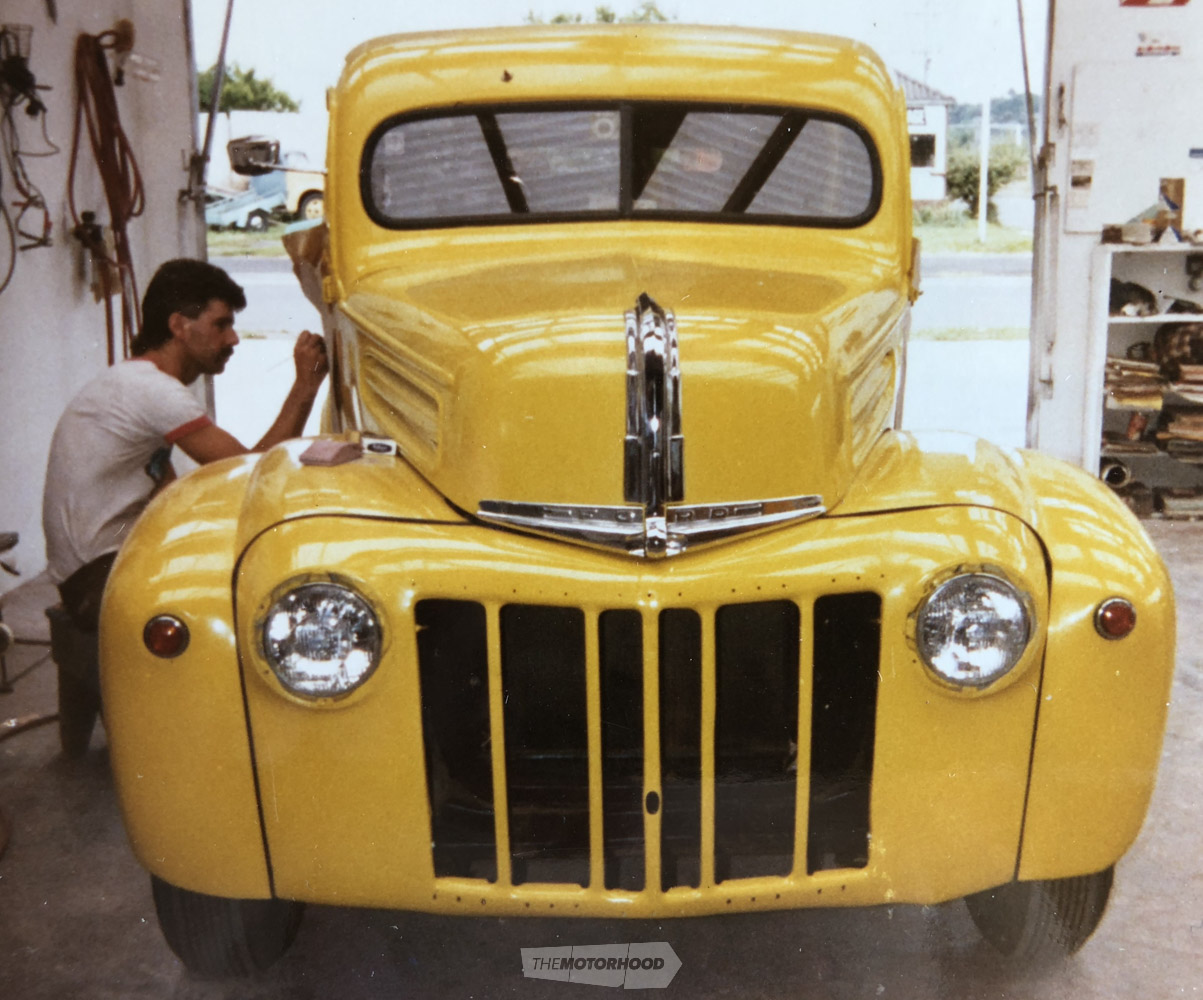

The void was filled by a 1948 Ford jailbar pickup that Grant bought as an unfinished project for next to nothing. A quick-and-dirty 302 Windsor was built out of spare parts lying around — back in the ’80s and ‘90s, he had the foresight to save or buy cheaply, and stockpile, every single overhead-valve Ford V8 block, crank, cylinder head, or other Ford engine part that he could lay his hands on — and he fitted a MkIV Zephyr gearbox and narrowed nine-inch Ford diff. It got a roof-chop, a quick coat of yellow slops, and its name ‘Diamond Dog’ hastily sign-written on its doors — twice actually, because I misspelt it the first time. It was rough, noisy, and a barrel of fun — and good enough for low 13s at Thunderpark dragway just outside of Hastings. Best of all, the finished truck owed him $1500 all up — a bargain even back then.

While Grant was building the jailbar, I was restoring a genuine XA GT351 four-speed manual Ford Falcon coupe, for which Grant rebuilt the tired engine. There were some strange things about the engine that Grant noted at the time, which we figured out many years later were due to the car being fitted (on the assembly line) with some Phase IV engine parts — notably, intake valves and, possibly, the complete cylinder heads. When the proposed XA Falcon-based Phase IV GT-HO ceased production, the parts earmarked for the cars got scattered into regular production. The finished car was an absolute rocket, and, by gently pedalling the skinny Firestone Cavallino tyres (necessary for the class I raced it in), I reset the national record at Thunderpark for B/Stock, one of the drag racing classes that existed back in those days, at 13.9 seconds at 105mph – a record that was never broken. This was Grant’s first notable engine-building achievement, and it was actually a bigger deal than either of us realized at the time, because what we didn’t know then was that the sky blue XY GT-HO Falcon of Brian Bowater that we took the B/Stock national record off was, in fact, the actual John Goss ’71 and ’72 Bathurst car and Sandown 250 winner.

Back in the mid 1980s, Thunderpark paid travel expenses to everyone who travelled from out of town and entered a proper class, so we’d load Grub’s old Diamond Dog pickup onto a borrowed trailer behind the Falcon coupe, and race both the Falcon and the truck, having a ball and collecting two lots of expenses. Both of us were in our mid 20s, married, mortgaged up, and on the bones of our respective arses. There were times that we’d be driving over to Thunderpark in the GT Falcon coupe towing the Diamond Dog behind us, with enough gas to get there — but wondering how the hell we were going to make the three-hour drive home — no Visa cards then — if the meeting was rained out and we didn’t get our travel money!

The go-fast bug had bitten Grant hard thanks to the jailbar and the XM Falcon before it, and so, in 1987, Grub bought a rolling T-altered chassis and body from the Hawke’s Bay in an effort to maximize speed while minimizing cost. Another Rivers-built 302 Windsor filled the hole at the front, backed by a clutched GM two-speed Powerglide, which Grant adapted onto the back of the Ford block — clutched autos were common then, as good torque converters weren’t around like they are now. The budget altered ran low 10-second passes, and, with terminal speeds of 136mph, the spare-parts 302 would have produced nines had it been fitted with a decent torque converter. The transmission was challenging, and Grant used a cast-iron flywheel to try to make the clutch slip enough to work properly. During one run, as he shifted into second gear at mid track, the flywheel flew apart, and, despite the presence of a custom-built steel bellhousing, the explosion smashed the back of the engine block off. As the ring gear tore off the flywheel, it actually flattened out from the rotational force being applied to it, and the teeth on the ring gear sliced the 5⁄8in solid-bar steering shaft in half — causing the steering-less altered to slam into the concrete wall. The impact was hard enough to relegate the chassis to the scrapheap, leaving just the candy blue–painted T-roadster body as a souvenir — which is still among Grub’s collection of memorabilia today.

To top off Grant’s shitty day, he arrived home a few hours later to find Fiona fuming because she was worried sick having somehow heard the news (no mobile phones or internet then) of the explosion and the crash while Grant was still driving home — and, of course, the stories that she’d heard (as happens when they’re retold a few times), were vastly worse than the truth!

DREAM CARS, ENERGY TO BURN

While racing the altered, Grant encountered a case of right car, wrong time. It wasn’t a runner when it came up for sale, but it was exactly his dream car — a 1965 Mustang fastback. Son Adrian had just arrived, and everything was sold, including Fiona’s daily-driver, to finance the Mustang’s purchase, to the extent that Fiona had to walk everywhere for six weeks until Grant had got the Mustang driveable and reliable. This is the very same black Mustang that, for over 30 years, Grant has drag raced, circuit raced, and tarmac rallied; that his kids Nicole and Adrian have both drag raced and circuit raced; that has been used for burnout demonstrations and hot rod runs; and that has served as an everyday driver. There are no signs of the Mustang being retired from any of that anytime soon.

Adrian’s arrival in 1988 caused a rethink in some aspects of Grant’s life. After a big crash while competing in motocross, leaving him with two knuckles missing and a steel plate in his right hand, Grant called it quits on bikes. Throughout Grant’s life and motor racing career, his wife Fiona has always been behind everything he’s done, from alcohol-fuelled funny cars, to Targa, to circuit racing, but she’s never been keen on bikes. In 40 years of bench racing, the only time I’ve ever heard Fiona say no to Grant’s plans and ideas, related to a drag bike. Given that two of the three drag racing fatalities we’ve had in New Zealand (as far as I can recall) have involved a trike and a drag bike, Grub might have something else to thank Fiona for.

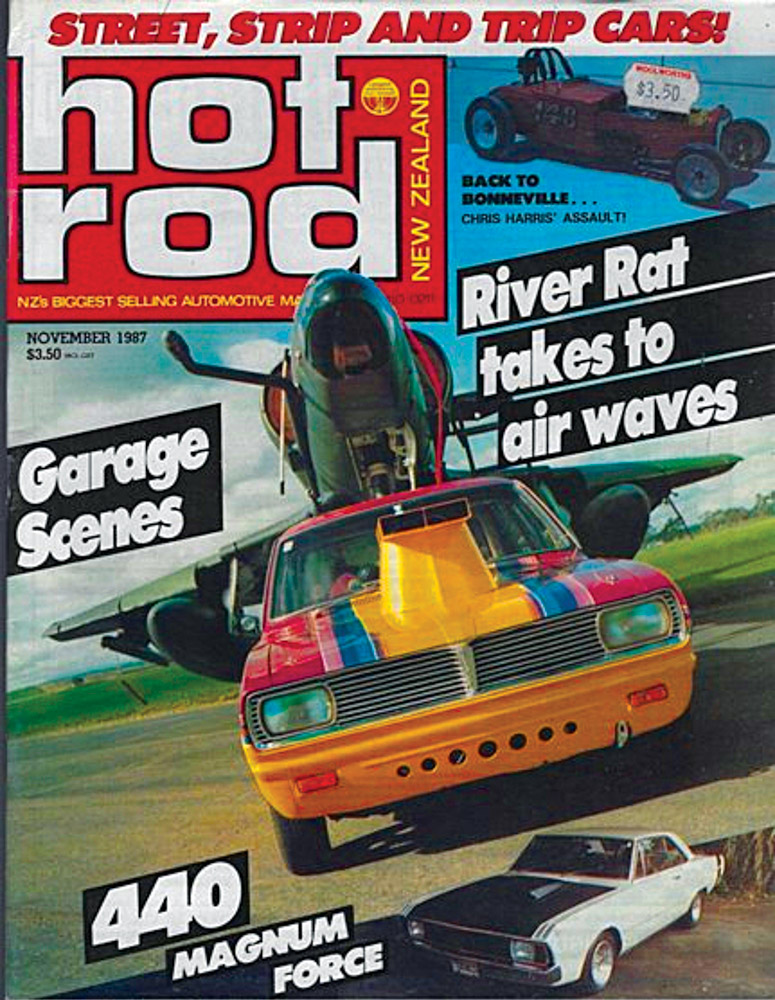

Another well-known Rivers project took place during the mid 1980s when Grant and I (both in our mid 20s) worked together to build my Vauxhall Viva HB street and strip car, which was called the ‘River Rat’. When I say that we built it, that really means that Grant did all of the clever stuff, and my engineering input amounted to doing simple stuff like cutting and grinding and drilling. In the space of three months of nights and weekends, I helped Grub where I could with panel work, a custom paint job, signwriting, parts sourcing, and organizing the upholstery and wiring. Grant Rivers — part man, part machine — built the rectangular-hollow-section (RHS) chassis, floor, tunnel, and firewall; narrowed the nine-inch Ford diff and mounted it on ladder bars and coil-over-shocks; narrowed and mounted an HT Holden front end; installed a rack-and-pinion steering system and column; installed a completely new braking system, including master cylinder and booster; and built the tunnel-rammed 396ci big block Chev and mounted it into the car, together with the transmission. Plus, he did all the little detail jobs — and got it running and sorted. It was a great little car. It ran 11s at 120mph, which made it, as far as we knew, the fastest steel-bodied street-legal sedan in the country at the time. After changing out the exhaust system, diff centre, spark plugs, and rear wheels and tyres, it was a daily-driver until I swapped everything back again for the next race meeting. Looking back now, that 90-night build was a hell of an achievement by Grub, but, of course, we never fully appreciated it back then.

Nowadays, it would take me longer than three months to even think about doing something like that. But Grant still does it, no problem. Approaching 60, he still has the focus, drive, and energy to still do today what we did in our 20s anytime he puts his mind to it.

LEARNING, TURNING, STARTING IN BUSINESS

Grant’s introduction to circuit racing came in 1987 through a friend, Ross Francis, who was racing an XT GT Falcon (Ross still races this same genuine GT Falcon today). After building a new engine for Ross, Grant went to a race meeting at Ohakea to help Ross. At some point during the day, Ross said, “Here, you jump in and have a race”. So, Grant suited-up, donned a helmet, jumped in, and had his very first car race. Without signing in. Without a race license. Without asking the meeting officials. “F*ck me, did we get a bollocking from the officials for that,” says Grub. “Poor old Ross even got fined over it!”

As the mid ’80s became the late ’80s, Grant formed a relationship with a local circuit racer by the name of Grant Taylor, who’d transitioned from club cars to a Chevrolet-engined Holden Commodore sports sedan (the predecessor to the Trans-Am). Adrian Rivers contributed to this car — sitting inside the car as a one-year-old baby while Dad worked on it, Adrian vomited up a stomach full of revolting-smelling baby milk all over the Commodore’s dashboard, steering wheel, and seat. “That was bloody gross!” Grub still remembers many decades later. “And what a f*ckin’ stink!” The sports sedan was a serious race car, and Grant had to come to grips with a long list of new mechanical challenges, including complex fuel systems, detonation, and the engine oil-surge issues that are inherent with circuit cars on racing slicks. What was sufficient for road cars and drag cars became entirely insufficient in the world of circuit racing, and high-level suspension geometry, steering geometry, and brake balance became new languages to be mastered by a young man still in his 20s. With no experience to draw from, Grub was thrown in at the deep end. There were never going to be any big successes while the competition included Rodger Freeth, Don Grindley, Wayne Huxford, and Kierin Wills — but Grant got on top of his learning curve quickly, and the junior team acquitted itself well.

By 1989, Grant Rivers was working as a motor mechanic by day for Iron Bridge Motors and by night for himself in his home garage in his pleasant and quiet neighbourhood. In that suburban environment, he’d built his altered, my Viva, Grant Moorhouse’s pro-street ’65 Mustang notchback, Rod Sklenars’ blown Windsor engine, and he was working on Grant Taylor’s sports sedan Commodore. Word was getting around, but the enthusiasm of his friends and customers wasn’t mirrored by his predominantly elderly neighbours.

It was Grant Taylor who convinced Grub to follow his heart and go into business for himself, and redundancy at his day job was the last bit of incentive needed. One weekend, in February 1990, Grub was away circuit racing with Grant Taylor while Fiona sat in hospital nursing two-day-old daughter Nicole as she wrote out invitation letters to prospective customers of the new business, which was to open in a week’s time.

With the brand-new ‘Rivers Speed and Spares’ sign hanging above the door, Grant’s customer base grew quickly. Local circuit racer Michael Eden came knocking (Grant still looks after Michael’s cars nearly 30 years on), as did Dave Rowan, who had by then bought my old Viva, and some local jetsprint guys. Steve ‘Tradge’ Rosewarne and Simon ‘Brick’ Watkins arrived at the Rivers Speed and Spares door one day with their 396ci big block Chev–powered flat-bottom race boat ‘Bad to the Bone’, and, after rebuilding the engine, Grant went through the boat from front to back, making it a reliable and competitive machine. Tradge later ran another flat-bottom called ‘Plum Crazy’, and, after having considerable success as a result of the Rivers-built injected big block Chev, Rivers Speed and Spares’ reputation quickly grew within the local powerboat racing scene.

All work and no fun will make us dull boys, but Grant Rivers was never a dull boy. Despite his huge work ethic, he was, and is, always up for a laugh and some fun. In the early days of being in business, he had a tiny little Yamaha 100 shop bike for picking up parts. One night, needing to get to a fancy-dress party at the hot rod club, Grant was pulled over by a cop while riding the Yamaha 100 through town with his hairy legs protruding out beneath a floral dress and wearing full make-up, including bright red lipstick (he makes the ugliest woman you’ve ever seen), with a bloke by the name of Chook — at 120kg — sitting behind him with his arms around Grub’s waist. The cop pulled them over just because it looked all wrong, but, after checking for a driver’s license and a warrant of fitness, shook his head and left them to it.

ANNIHILATING THE OPPOSITION

One night in 1993, at a pub after a powerboat race meeting held on the Whanganui River, a bloke came up to Fiona and got chatting with her and asked her if she thought Grant might be interested in helping him. His name was Warwick Lupton, a farmer from the small town of Waverley in South Taranaki, and his boat was called ‘Annihilator’. Warwick was — and still is — a massively serious and committed blown hydroplane racer, but, at that time, his engines had been blowing up with such regularity that he’d become known in the boat racing scene as ‘One-Lap-Luppy’. Grant and Warwick had a long talk that night over a few pints, and Grub learnt that Warwick had all of the parts for a brand-new engine, but, given how long Warwick’s engines had been lasting, his current engine builder was reluctant to build it. Before committing to anything, Grant agreed to look at the old engine first, which involved stripping and inspecting it, and creating two piles. When Warwick arrived at Grant’s shop the next day, he learnt that everything in the small pile could be reused, while the big pile was only good for the rubbish skip. It was a big punt for Grant to say to Warwick, “OK, I’ll build your engines for you”. He’d never built an alcohol engine or an endurance engine in his life, and it didn’t help when he heard that there was a lot of speculation that he was getting out of his depth — in fact, Grant learnt that the crew chief of a competing blown hydro had said, “This will be interesting — he only builds engines that have to go for 10 seconds.”

Rather than building the brand-new engine, Grant elected to rebuild the old one first. Under the pump, with a short space of time before Warwick’s next race meeting, Grant spent night after night trying to understand what had been going wrong for Warwick by analysing the old engines and their various parts. He figured out that Warwick’s engines had been blowing up because they’d been using the wrong piston design for the application, the fuel system was set up incorrectly, and the engines had been leaning out. After several trial assemblies and tear-downs, Grub finally took a deep breath and declared it ready. Warwick’s first big meeting with the old Rivers-built engine was the 1993 Griffith Cup at Lake Karapiro. By the time the finals came around on Sunday, the only piston-engined boat still going and capable of taking on the big turbine-powered machine from overseas was Annihilator. Every other boat in the field had killed its engine trying to — unsuccessfully — get to the final. The critics were silenced. One-Lap-Luppy’s nickname was quickly forgotten as he went on to win every major trophy in New Zealand, including the Griffith Cup twice, the world series twice, the Masport Cup, the Baker Cup, and the New Zealand championship numerous times. The man who only built “engines that have to go for 10 seconds” still remains today the only engine builder ever to have built the winning engines for both of the V8 powerboat categories in the same season. The relationship between Grant and Warwick was cemented, and is still going strong today, 26 years later. The Rivers and Lupton team has done more than a dozen trips to Australia to race there, and, in 2018, went to race at Valleyfield in Canada for the 80th running of the prestigious annual Valleyfield Hydroplane Racing League race meeting, where they won the final by 10 boat lengths but lost the win because of a 0.5-second jumped start.

Warwick runs three hydroplane racing boats — the others piloted by his son Jack Lupton and nephew David Alexander — and, between the three boats, Grant looks after no less than six 510ci blown-and-injected alcohol Chev engines. Imagine them lined up inside a transporter! Grant’s commitment to Warwick’s racing programme is absolute, and when you don’t see Grant and his family racing at a big drag race meeting or circuit race meeting, that’s because Warwick’s deal always comes first. There’s a well-known story about the massive regard in which Grant Rivers is held within the hydroplane racing scene — after winning the Griffith Cup with Annihilator in 2001, Ron Burton — a wealthy Australian who runs multiple hydroplane racing boats over there — offered Grant an annual salary of half a million dollars to shift to Australia and work exclusively for him. Grant’s unhesitating response to Burton was (referring to his relationship with Warwick), “No thanks. Money can’t buy friendships or happiness.”

RODS, RACING, AND REPUTATION

By 1993, the Rivers Speed and Spares business had outgrown its rented building, and a block of land was purchased and a new building put on it. Grant shifted into this 1994 and remains there today. That same year, the Rivers Speed and Spares signage appeared on a new shop truck — another Ford jailbar pickup, this time bright orange, roof-chopped, and another 302 and four-speed. Even the ETs of 13.0 were exactly the same as those of the old yellow one from a decade before. At around the same time, the black ’65 Mustang, which Grant had enjoyed using as a road car over the past five years, received some modifications and began its motor racing life. Grub started racing it in classic motor racing events at Manfeild and Taupo, and success came quickly. And that’s never stopped — today, 20 years on, it’s the same car, the same tracks, and more trophies.

During those early days of learning the ropes in hydroplane racing, other things were happening that were resulting in the positive growth of the Grant Rivers reputation. Michael Eden brought ‘Old Blue’, the famous XY Falcon that he’s been racing for over 20 years now, and Grant has been on that journey all the way through. Grant has recently built a brand-new engine for the Falcon, after its previous Rivers-built race engine was finally retired after 12 seasons of abuse within classic racing and CMC competition — without having to be touched.

Another reputation Grub was gaining in those days was for injuring himself, and he helped his reputation in this department along at Willie Roach’s 40th birthday party in New Plymouth sometime in the late 1990s. Grub had been on it throughout the afternoon, all night, and was one of the last ones still going at 5.30am when, while sitting upright on a stool with a beer in his hand, he fell sound asleep and toppled forward face-first onto the floor, breaking his nose and spreading blood and beer all over Willie’s kitchen. When he got back to Whanganui, he had to go to the hospital and get his nose re-broken and set in a cast. The following weekend, he had to go to the drags but couldn’t race because he couldn’t fit his helmet over his great big, stupid-looking nose cast. You can imagine the rubbishing that he got from all of his racing mates as he walked around the place looking like a skinny woodpecker.

APPROACHING THE NEW MILLENNIUM

Grant had also been helping Dave Rowan with the old River Rat Viva, now painted bright red. Dave had been looking for an engine for the car (which he bought minus an engine), and ended up buying the blown big block Chev engine from the ‘Devil Woman’ A/Street rod from Eddie Fairbairn in 1993. In street trim and on pump gas, the Viva ran 10.2 seconds at 136mph. Dave sometimes raced the Viva initially, and once had the unfortunate experience of breaking a right-side axle at the flange, and, as he felt the lurch and wisely lifted off the gas, he saw the right rear wheel and tyre rolling down the track past him towards the finish line. The old Viva was so over-engineered as a result of the naivety of its 20-something builder that, when it lost the wheel and tyre, it just dropped down onto the wheelie bars, which didn’t even bend as they supported the corner of the car. With the left rear wheel still driving, Dave could have driven it back to the pits if he wanted to! By 1996, thanks to lessons learned from tuning the blown hydroplanes, the ex-Fairburn blown Chev had been fettled by Grant to the point at which the hotted-up street Viva had become an over-engined monster, nudging at the eight-second zone at over 150mph.

By this time, Grant was doing all of the driving, and, during a race at Thunderpark dragway against Robin Silk, Silky flicked up a stone (probably not intentionally!) from the other lane just past the finish line, and Grant ended up with the Viva’s windscreen — an old toughened-glass screen rather than a laminated one — in his face and lap at 152mph. The bad news was that his visor wasn’t down, but wearing sunglasses saved the day — and his eyes. This was a sharp reminder that things were happening quickly now, and perhaps this wasn’t the right car in which to be going this fast. So, as the ’90s approached the 2000s, and the partnership with Dave Rowan was going well, Grant and Dave decided to chip in together to put the power in the engine bay of the Viva into something more sensible, and the search began.

This would be the start of a long, exciting, and challenging alcohol-engined journey, which, on and off, Grant is still travelling along now. Meanwhile, Adrian and Nicole were growing up and watching the other kids in Junior Dragsters, and Grant was eyeing up more circuit racing and the Targa. If people thought that Grant Rivers was a busy guy back then, he was only warming up.

Check back later for the rest of this tale in part three!