The story of Robbie Francevic’s Ford Fairlane goes to show that not all classic racing stories are rosy ones!

“I should have blocked him a bit better, but he got me and then we went side by side, and it was pretty good racing, but I don’t know what happened up there. I just plucked her in first, gave her some jandal, ’n’ f#%k yeah!”

Young Kiwi racer Scott McLaughlin shot to stardom earlier this year, having beaten reigning V8 Supercar champion Jamie Whincup in a head-to-head for second position in Race Two at the Clipsal 500. His post-race interview will go down as one of the most memorable in recent years and has won him an army of fans.

But the rapid rise to the pointy end of the grid for McLaughlin and Volvo (remember, Scott is only in his second year of V8 Supercars and Volvo its first) has prompted Channel 7 television commentators to keep referencing another fast Volvo-driving Kiwi who beat the best Australia had to offer nearly 30 years ago: Robbie Francevic.

Francevic vaulted onto the Aussie racing scene in 1985 — the first year the Australian Touring Car Championship (ATCC) was held under Group A rules — in an unlikely turbocharged Volvo 240T. His was an ex-Eggenberger car, out of Europe and very fast, and he was immediately competitive, eventually going on to win the 1986 ATCC. But, two decades, prior to that, Francevic was making a name for himself in his homeland, with a couple of unlikely race cars that left an indelible impression on the Kiwi motorsport scene.

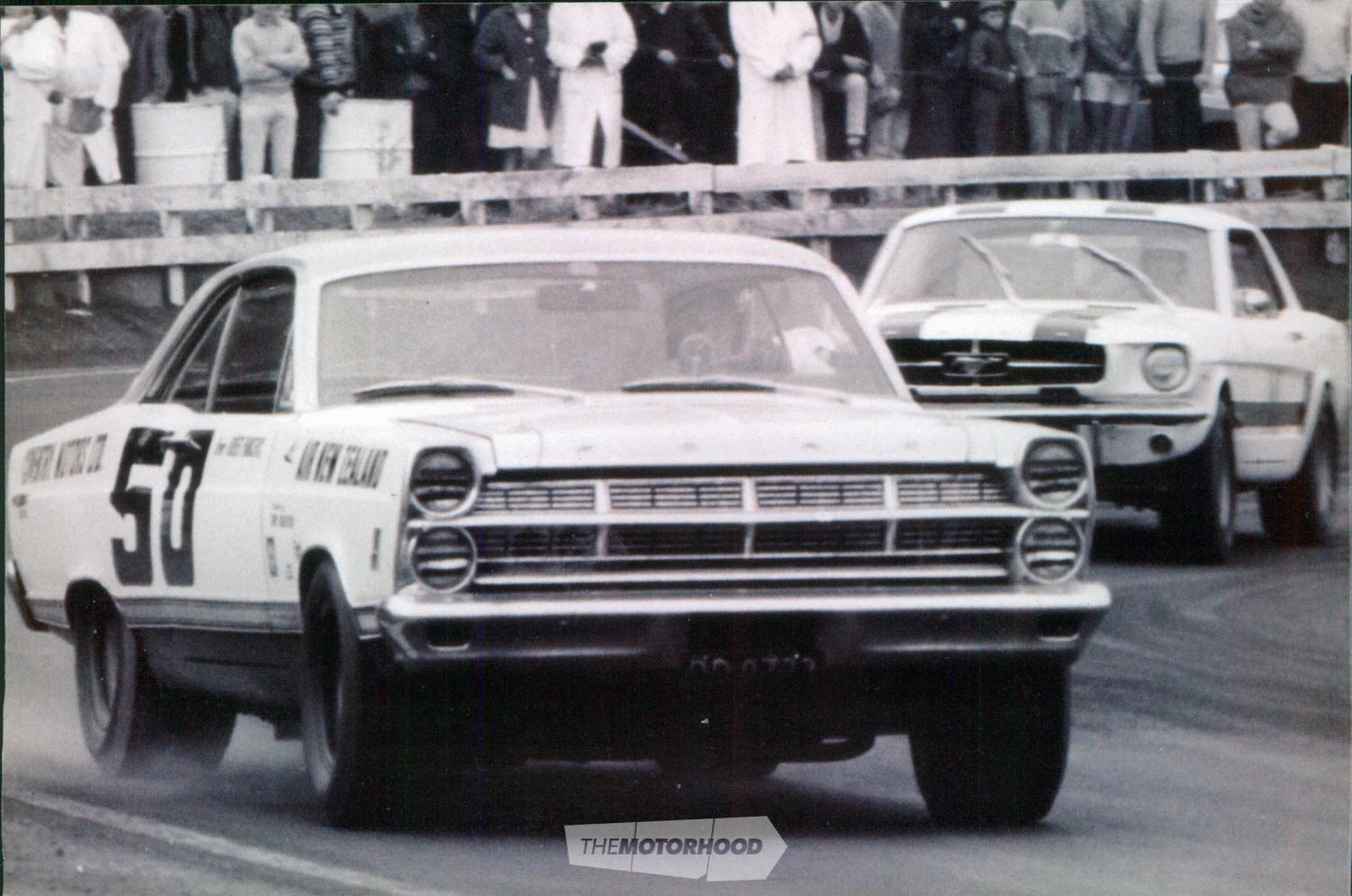

The first of these was the ‘Custaxie’, a heavily modified mid-1950s Ford Customline fitted with a 427ci Galaxie motor (hence the name), with which Francevic won the 1967 New Zealand Saloon Car Championship. The second Francevic big block monster was a mighty Ford Fairlane, also 427 powered, which replaced the Custaxie in 1968. Much has been written about the Custaxie over the years, and there has even been a replica built recently, but the Fairlane has enjoyed very little media coverage and little is known about the car. However, a cool photo I was sent last year to post on theroaringseason.com prompted me to find out more.

Here is the email that accompanied that photo:

Hi Steve

Didn’t know if / where this sort of thing might go on your site, but if you’re interested, this is a pic of Robbie Francevic and Tony Kriletich (outside Robbie’s place, from what I remember).

I’ve got pics of Tony working on the Custaxie somewhere, and some 8mm of races.

As a young thing, I spent many hours hanging around the garage watching [Tony] boring and grinding. [He] is my uncle.

Cheers

Paz

Back in the mid 1960s, the New Zealand Saloon Car Championship (held under ‘allcomer’ regulations) featured almost no rules. As a result, competitors built some pretty feral race cars. The 1966 championship was won by Dave Simpson, driving a Ford Anglia that featured a heavily revised nose for improved aerodynamics and a fastback ‘bread van’ roof, and was powered by a twin-cam Lotus motor. Paul Fahey, Simpson’s nearest rival in the championship, raced a very similar car. Given how much faster these two cars were than their competition in 1966, most teams opted for a similar concept for 1967 — that is, fitting a powerful motor into a small, nimble, lightweight bodyshell. The exception was a couple of young Auckland racers called Robbie Francevic and Tony Kriletich, who chose a completely different route with the Custaxie.

Francevic dominated the 1967 championship, finishing second in the first three races, before fitting a limited-slip diff to the Custaxie and going on to win the remaining four. But before the 1967 season even got underway, the Motorsport Association of New Zealand (MANZ) announced that this would be the last year for the allcomer cars, with the more production-based FIA Group 5 regulations being drafted in the following year. With that announcement, virtually all the allcomer cars, including the Custaxie, would have nowhere to race beyond 1967, and their owners would need to find themselves replacement machinery in which to enter the 1968 championship.

For Group 5, four classes would be contested: 0–1000cc, 1001–1300cc, 1301–2000cc, and over 2000cc. Although there were some impressive showings by small-capacity cars in the UK and Europe, most notably the Lotus Cortinas and Mini Coopers, most considered that the over-2000cc class would provide an outright winner. Indeed, most who competed in this class — including Paul Fahey, Rod Coppins, Red Dawson, and Frank Bryan — opted for the tried and tested Ford Mustang.

But much interest surrounded the reigning New Zealand Saloon Car champion and what he’d be armed with to defend his title. In June 1967, Francevic and Kriletich boarded a plane for the US, where they would take in some dirt-track speedway racing with the Automobile Racing Club of America (ARCA). ARCA founder and president John Marcum arranged a Ford Galaxie stock car, along with a truck and spares, for Francevic and Kriletich, and the big Kiwi put in some impressive performances, claiming several top-five results. He received additional support from Air New Zealand and Champion Spark Plugs.

Perhaps it was the experience with the 427ci Galaxie on the tight little US bullring ovals that prompted the decision to race a similarly powered Ford Fairlane in the 1968 NZ Saloon Car Championship. The announcement was made late in 1967. The big block 427 was said to be good for 550hp, which would make it the most powerful car on the New Zealand racing circuit — by some considerable margin. Continuing the stock-car theme, the Fairlane was fitted with eight-inch–wide steel wheels, rather than the mag wheels most other competitors chose. In the US, Ford had opted for the 427-powered Fairlane to replace the larger Galaxie in nascar competition for 1967, and Nascar included both road courses and ovals, which may also have helped Francevic and Kriletich make their decision to run the Fairlane. Certainly, they proved in 1967 that bucking the trend and thinking outside the box could produce rewards.

Backing the big 427 was a 31-spline main shaft close-ratio Ford Toploader gearbox, with a Detroit Locker rear end, 31-spline axles, and non-floating hubs. Brakes were Mustang Kelsey-Hayes discs up front and finned drums at the rear. Air New Zealand continued its support, while the Fairlane also featured signage from Coventry Motors, the Urquhart family–run garage that had supported the Custaxie in ’67.

The opening round of the eight-round 1968 championship kicked off at Pukekohe on November 4, 1967. As the big and impressive field of Group 5 machinery blasted off the line for the first time, the Francevic Fairlane was not among them — it was ready, but it didn’t race. Under Group 5 rules, the Fairlane was not yet homologated to race, and, rightly or wrongly, MANZ stuck grimly to the letter of the law. The Fairlane was also absent for round two — the Auckland Car Club–run event — also held at Pukekohe.

Bay Park hosted its annual Christmas event on December 30, 1967, with Aussie hard-charger Norm Beechey and his Chevy Nova the main drawcard. Although it was a non-championship event, all the leading local teams were in attendance, including Francevic, finally getting to run the Fairlane for the first time. As it transpired, it was an unhappy day for the team, as overheating issues dogged the big machine and it failed to reach the finish in either encounter.

The New Zealand International Grand Prix meeting played host to round three of the championship, and, with homologation papers at hand, Francevic and the Fairlane made their first championship appearance. Having missed practice, Francevic started off at the back of the small field, but, after one lap, had powered his way up to third behind the Mustangs of Fahey and Bryan. Then the overheating issues reared up again, and the Fairlane was out by lap six.

The tiny Levin track hosted round four, and the Fairlane belted around in practice, with smoke trailing along behind as oil leaked out from the rocker covers. In the opening heat, Francevic ran fourth behind Dawson, Fahey, and Coppins, before pushing Coppins back a spot. But then he dropped off the track and slipped down the order. In the second race, he ran third for a time before being displaced by Aussie visitor Brian Foley in his Mini Cooper. Then the Fairlane dropped out altogether, with a holed piston.

Francevic missed round five at Wigram, waiting for a replacement piston to arrive from the US but returned for the next round at Teretonga, where the overheating issues continued to haunt the team. Francevic qualified fourth but retired from both the championship race and the non-points-paying invitational due to overheating. The final two championship rounds at Timaru and Ruapuna produced no further joy.At the annual Bay Park Easter event, in April 1968, with Aussie Mini Cooper drivers Don Holland, John Leffler, and Lynn Brown all in attendance, Francevic battled with Holland and, in cool conditions, scored a much-welcomed second place behind Fahey. In the second heat, in wet conditions, the big machine took its first race win. However, in a third race, the motor blew.

A week later, at the Dunlop half-hour event at Pukekohe, the Fairlane was back, this time sporting a fairly drastic answer to the ongoing overheating issues: the grille, headlights, and front bumper had all been removed, leaving the large frontal area of the car a great black hole with only a radiator mounted in the middle.

In the opening preliminary, Francevic emerged in the lead, after Coppins had taken avoiding action following a wildly spinning Leffler at the opening corner. Francevic held the lead throughout the first lap before Fahey passed him on lap two. Then the gearbox blew, and Francevic was out for the rest of the event. With that, the big spectacular Fairlane was not seen again. MANZ introduced a new maximum engine limit of 5500cc for 1969, so the Fairlane was effectively outlawed after just one season. For Francevic and Kriletich, this was the second year in a row their car had been outlawed by rule changes.Sadly, the Fairlane’s fate was as unfortunate as its competition career. It was converted to a road car and eventually met its demise in a garage fire in the South Island around 1972. Some parts were salvaged and ended up on other race cars; the mangled body was crushed and used as landfill.

But it was an interesting car, and it is a fascinating story about beating a different path to try to get ahead. Too bad it didn’t have a happier ending.

This article originally appeared in NZV8 magazine issue No. 110 to get your grubby mitts on a print copy, click the cover below