Chris Piaggi’s chopped and channelled ’38 Ford coupe is the very essence of hot rodding — speed first, everything else second!

“I wanted the car to wheel stand,” Chris Piaggi explains of his ’38 Ford’s immense engine setback. That simple sentiment explains a lot about the hot rod you’re looking at. There is no pretension about it — everything you see was done either to make it go fast or to look tough. To a young Chris and the kids he called mates back in the ’70s, hot rodding came as naturally as breathing. Many of those kids are still mates to this day, but, for the purpose of this article, one must take priority — Kevin Perry, who had purchased a ’38 Ford Deluxe coupe off a friend.

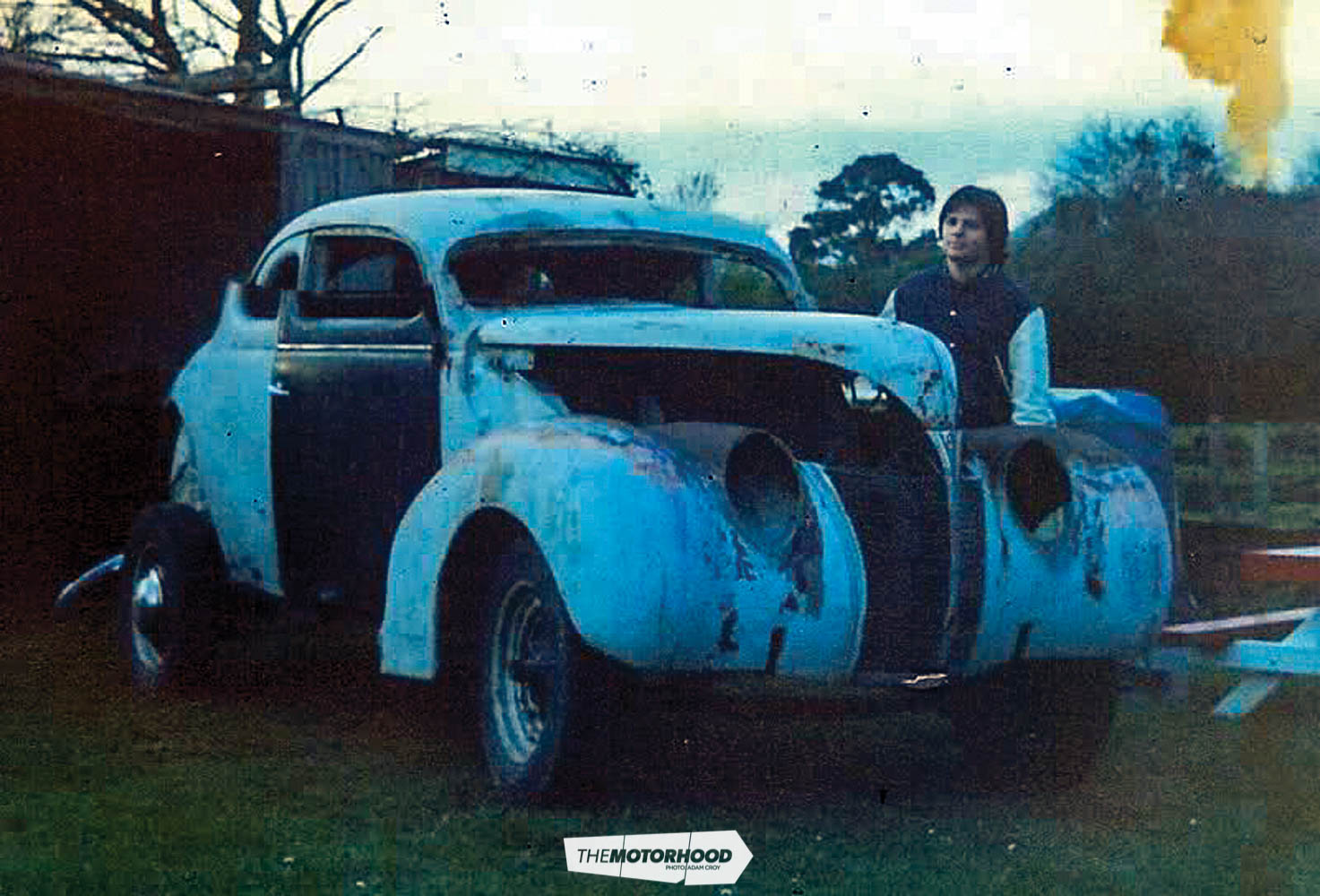

“It was a stock rolling shell of a ’38 [Ford] coupe, minus engine and transmission,” Kevin recalls. “I couldn’t wait to chop the top, but cutting across the top was too intimidating for me, so I decided to lay the posts back. Soon after [in 1979], I decided to move to the States, so I sold it to my good friend Chris, [as] a stock rolling shell, less engine and with a radical chop.”

Eight hundred bucks later, the coupe belonged to Chris. “I don’t think I even had a garage at home,” Chris mentions, “so I bought a second-hand Skyline [garage], and my brother and I put it up on my parents’ back lawn.”

View fullsize

View fullsize

Since the coupe looked fast standing still, a fast car it would have to be — something that would lift the front wheels on take-off. To this end, the firewall was cut out and a 272ci Y-block and T-10 four-speed were mounted about 24 inches rearward, using a ’58 Ford cross member. The spring mounts were cut off the existing ’38 diff and welded to a ’58 Ford nine-inch, to be hung off the ’38 transverse leaf spring, while a set of extra-long ladder bars was fabricated to mount below the gearbox cross member. In true hot rod style, the front axle was drilled and remounted, hanging off split radius rods. With the grille and bonnet refitted, the coupe was rolled out onto the road and inspected from every angle.

“It looked good but was too high,” Chris says, “so it was back into the shed, and we channelled the body the width of the chassis.” There’s no denying the effect this has had, as it is one of the key reasons the coupe looks so mean. This development also saw the addition of a 332ci FE for even more power, despite the fact that Chris had yet to drive the thing. He wouldn’t be doing so any time soon, either — in the early ’80s, a holiday to the US with friends soon turned into a move to California, where he managed to score a job at Moon Equipment.

“While buying some flathead parts, I asked if there were any jobs going. Dean [Moon] asked me a bunch of random questions that I must have answered correctly, as he said to come back on Monday for a trial run,” Chris says. Starting at the bottom, feeding Nitro the guard dog and picking up innumerable dog turds, Chris worked his way a few rungs up the ladder, working with Dean as well as hot rodding legends like Bill Jenks and Fred Larsen. The knowledge these guys had to impart wasn’t lost on Chris, who honed his skills while taking in as much of the Californian car scene as he could, managing to catch up with mate Kevin at most swap meets.

Living and working in California, it didn’t take long for Chris to aspire to own the ultimate Ford engine — a 427 side-oiler. Realizing he could never afford a complete one, Chris did the next best thing: guided by hot rod magazines, he collected the parts to build one from scratch, with his role at Moon Equipment opening doors that would otherwise have remained shut.

“What got me started was a bare-block 30-thou-over for $500 from Ford Power Parts. Next was a 428 Cobra Jet crank, machined at Velasco Crankshaft Services, 427 Lemans rods from Keystone Ford in Norwalk, and Arias forged stroker pistons from Speed-O-Motive,” Chris recounts.

View fullsize

View fullsize

This pile of parts was added to with a steel flywheel and clutch assembly from McLeod Racing and a pair of 428 Cobra Jet heads that had been rebuilt by George Striegel at Clay Smith Cams. George also shot-peened the rods and balanced the rotating assembly, before Chris assembled it under the watchful eyes of Bill Jenks and Fred Larsen, who ground a custom camshaft to suit. When it came time to return to New Zealand, Chris packed the big motor and his substantial parts collection into a crate and shipped it all back — a real ’80s crate engine!

Back home, the original plan for the coupe went out the window, as Chris decided to build a pro-street race car, starting with the chassis. The front rails were boxed, and, with an Alston Chassis catalogue as a guide, Chris fabricated a 4×2-inch box-section rear half. Service Engineers narrowed a large-bearing nine-inch, which was hung off a pair of modified Triumph Herald coilovers and custom ladder-bar set-up. The mechanical improvisation continued up front, with a Super Bell dropped axle and batwings used with home-made four-bars and the original transverse leaf spring. With the bones complete, the neglected bodywork came next.

“I wanted a fibreglass front end, and thought a ’40 Ford pickup tilt front from Gemini Plastics would be close — I was wrong!” Chris declares.The ill-fitting front end had the fenders cut off and flanges glassed in, allowing them to be bolted on. As a genuine ’39 Ford grille proved too expensive, Chris bent a bunch of steel rods, making a ’39 Mercury–style grille with horizontal slats. Completion of the grille meant work could begin on the hood, which was cut down the middle, narrowed, and reshaped at the rear to match the ’38 cowl.

Despite his talents, Chris knew when to step back, delegating the rear to panel wizards Terry Sims and Mike Roberts, who grafted in a pair of tubs and repaired the rear fenders and boot lid. Once the coupe returned to his garage, Chris finished the floor and other missing pieces, and fitted a Bakelite dashboard from a Ford Pilot that he’d found in the inorganic collection. With the car finally resembling a real-deal hot rod, Michael Hamlin (RIP) and his brother Steve were enlisted to help with the bogging. By the time the body was reunited with the chassis, Chris was hanging out for a test drive.

“No doors, no front panels, no rear guards, no windows,” he recalls. “The power of the 427 was quite overwhelming, especially with the trick hydraulic throttle I had fitted, which was very slow to return after full-throttle runs!” Work continued steadily, and, when the coupe was ready for paint, there was only one option to match its no-nonsense attitude — satin black. Chris can recall a whole lot of good times the badass hot rod gave him and his mates — like the time Steve Hamlin and Mike Roberts decided to take it through the Georgie Pie drive-through with open headers — even though it would have been quicker to walk from Chris’ workshop!

“We also used to go into town and around the waterfront, and intimidate the would-be boy racers,” he remembers. “Not one of them wanted to race us! The car was still drivable with the 4.56[:1] diff gears and 31-inch-tall tyres, but it used a lot of gas.”

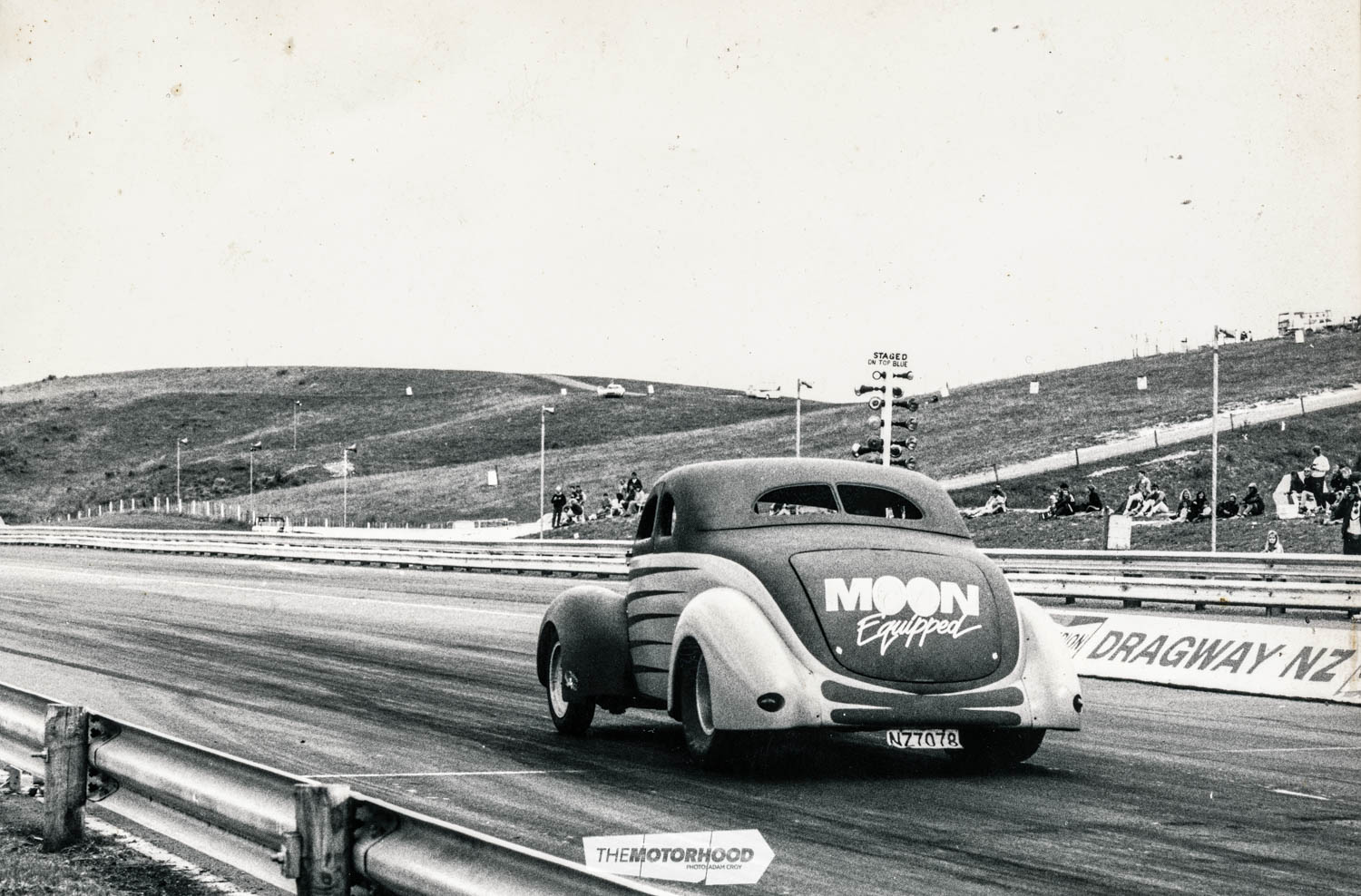

To let that big 427 really breathe, it was let loose at a few Nostalgia Drags meetings, and, although it never did wheel stand as Chris wanted it to, ETs in the mid-to-low 12-second zone are pretty damn impressive for a home-built street car of the era. It could have gone quicker — but then a friend lent Chris his nitrous kit.

With the kit installed and ready to go, Chris couldn’t wait to give it a try. On his first run, the nitrous kicked in just as the car hit the dip in the track, spinning the tyres and sending the car sideways off the track and backwards into the fence, before it rolled over into the swamp. Once racing had finished, the battered coupe was retrieved, and, miraculously, Chris was able to drive it back to the pits under its own power — to the delight of the crowd. You can’t keep a good Ford down! “I’m never trying nitrous again!” Chris laughs, recalling the incident.

View fullsize

View fullsize

The damage was extensive, but far from irreparable, and once all the repairs had been made, Chris hung up his helmet and pulled the 427 side-oiler and 4.56:1 gears out. The addition of a 390 FE up front and 3.0:1 gears out back saw the once-wild hot rod tamed and used mainly for cruising duty before being parked up in the garage, where it’s spent most of the past decade. Chris and his friends still take the coupe out every now and again, and Chris recalls the time Kevin came back to New Zealand and took it to the Nostalgia Drags. The clutch wasn’t good enough for it to race, but the connection of close to 40 years more than made up for it.

“It still gives me a sense of contentment when I roll her out into the daylight — even after 37 years,” Chris says. It’s rough, ugly, and a bit of a pig to drive, but it’s more than just a car to Chris; it’s an integral part of his life — not just because of the 37 years he’s owned it, but because he could own it for another 37 years and still feel the exact same way about it.

Chris Piaggi

Car club: Scroungers Car Club, North Shore Rod and Custom Club

Age: Old enough

Occupation: Mechanic

Previously owned cars: Numerous, and I still own half of them

Dream car: Tony Nancy’s SCoT-blown flathead Model A roadster on ’32 rails

Why the ’38? Cool car, right place, right time

Build time: 37 years

Length of ownership: 37 years

Chris thanks: Whoever has helped out with the car; Kelly and Carson for putting up with my addiction

1938 Ford Deluxe coupe

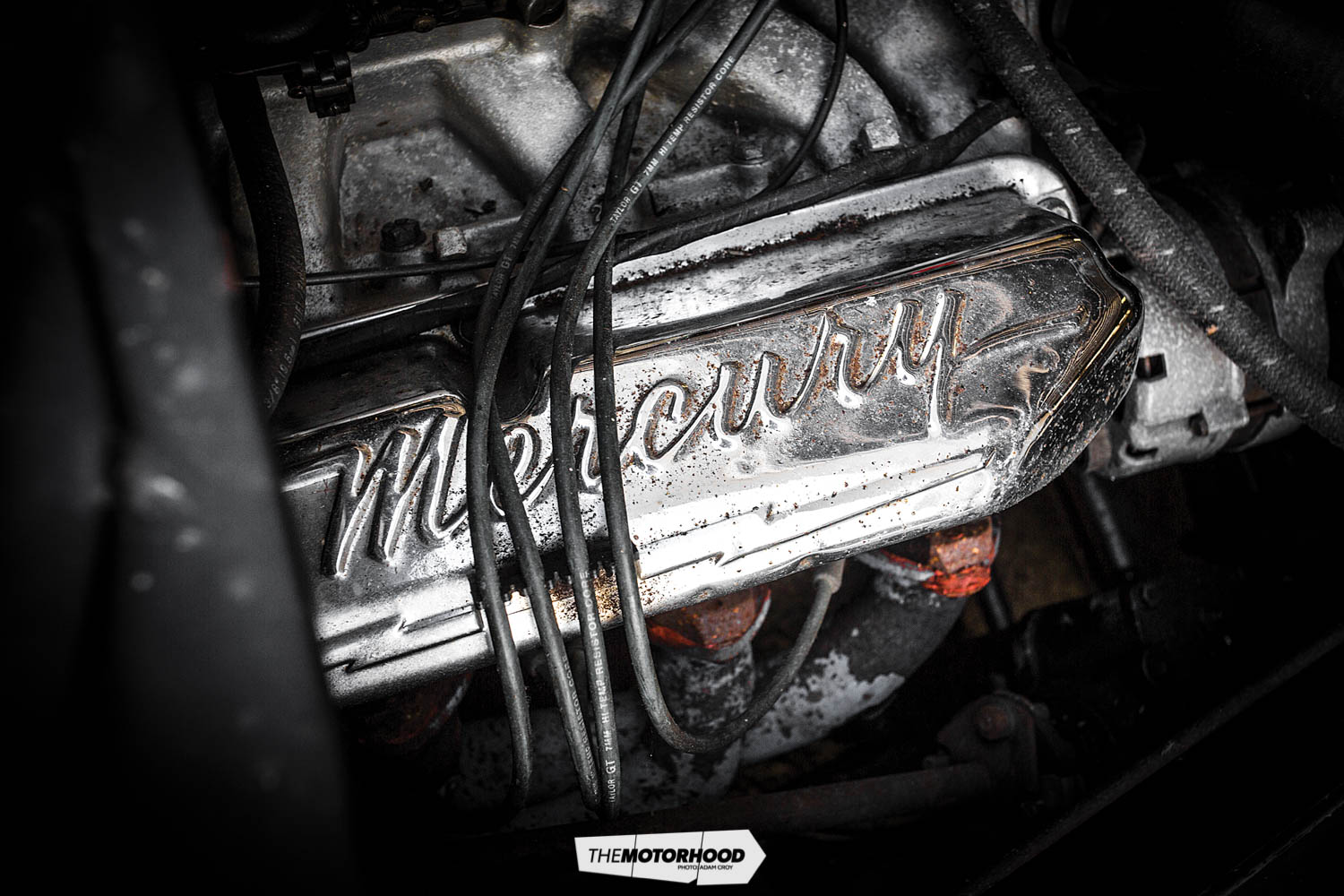

Engine: 390ci Ford FE, Holley intake manifold, Holley carburettor, Hooker headers, Mallory distributor, Mercury rocker covers

Driveline: BorgWarner T-10 four-speed manual, Lakewood scatter shield, standard clutch and pressure plate, Ford nine-inch diff, big-bearing diff housing, 3.0:1 diff ratio

Suspension: Four-bar front suspension, Super Bell dropped I-beam front axle, Porirua Machine stub axles, ladder-bar rear, Triumph Herald rear coilovers, adjustable shock mount brackets, Holden HT steering box

Brakes: Holden single-piston front calipers, Leyland P76 front discs, Ford rear drums

Wheels/tyres: 15×4-inch Steelie Wheels alloy front wheels, 15×10-inch Thompson Wheels alloy rear wheels, 310-13.0-15 Hoosier rear tyres, clip-on front whitewalls

Exterior: Fibreglass front fenders, custom fibreglass hood, frenched headlight bezels, custom grille, recessed firewall, channelled body, custom floorpan, chopped roof, frenched ’59 Cadillac tail lights, fibreglass boot lid, matt black paint, custom flames

Chassis: Boxed standard chassis, custom rear section

Interior: Bucket seats, Hurst vertical-gate shifter, deep-dish steering wheel, Ford Pilot Bakelite dashboard, Stewart Warner gauges, Speedwell rev counter, roll cage

Performance: Untested

This article originally appeared in NZV8 issue No. 149 — to get your grubby mitts on a print copy, click the cover below