Dyno tuning can be a confusing topic among car enthusiasts, with misinformation and differing opinions in circulation. We talked to a few experts to clear the air

The dynamometer and the tuners behind them are an essential part of the car-modification process. No matter what you’re building — a carbed classic, a reflashed street car, or an all-out race build — time on the dyno isn’t cheap, but it’s just about the best money you’ll spend on your car.

Tuners use a large range of dynamometers from many different manufacturers — 2WD, 4WD, engine, rolling-road, hub — all have their pros and cons, so make sure you do your research before committing.

In the same vein, don’t forget to ask around, check out reviews, and make sure you’re 100-per-cent happy with the person who will actually be tuning your car. Although New Zealand is pretty good when it comes to tuners, it pays to bank on reputation and service, not on whoever is cheapest. Remember, this person will be trusted completely with what probably represents a good chunk of your yearly salary — this isn’t someone driving your car around the block a couple of times; this is someone teaching your car how to run, with all the ups and downs that come with that.

On the flip side, you might have chosen the best tuner in the world to take your car to, but, if your gear isn’t up to the task, then you’re going nowhere and wasting money. Best-case scenario: the tuner recognizes your car’s shortcomings and refuses to put it on the rollers until it’s sorted; worst case: the tuner has no way of knowing that your motor set-up isn’t up to scratch, puts the car on the dyno, and it pops, leaving everyone out of pocket and a high likelihood of the situation devolving into a blame game.

In many countries, enthusiasts have to travel huge distances to put their car on a dyno; we’re very lucky here in New Zealand to be surrounded by great dynos and the brilliant tuners who operate them. We were able to chat to a few to fill in some of the blanks and misconceptions around the art of dyno tuning.

Dave Heerdegen at Dtech Motorsport says:

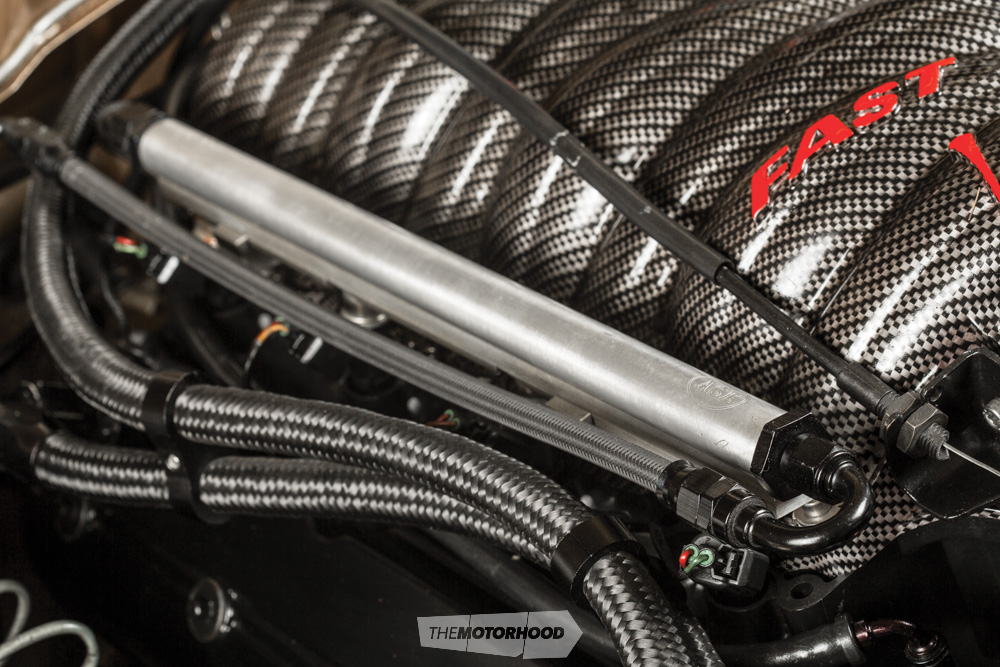

“The end result of any engine upgrade is the sum of the pieces fitted. If you think of an engine as an air pump, the more efficiently the air enters and exits the cylinders, the more potential there is to make horsepower and torque. In most cases, a typical dyno tune is about making sure there is the correct air to fuel ratio to support the rpm and load on the engine, as well as to optimize the ignition advance curve to suit. A typical dyno tune should be undertaken at the end of any upgrade, to maximize the potential of the parts safely. Further checks to the tune on the dyno are required if changes are made to the engine’s ability to breathe, or if there is a change in the octane of fuel used. This will confirm both whether there have been any losses or gains in power and the safety of the engine.”

Glen Jennett at Engine Specialties says:

“Both chassis and engine dynos are relevant, and both have advantages and disadvantages. On an engine dyno it is a lot easier to change components while doing back-to-back testing to achieve the best result. The chassis dyno has the advantage of the testing being done with your components, your fuel system, your ignition and wiring system, and your exhaust. The results often vary from one to the other. However, bear in mind that dynos can be manipulated to give higher readings; by changing air temperature input you can alter power readings dramatically. Ask your operator to see if his dyno is running on a live weather station or pre-programmed figures.”

Engine v. Wheel Power

We’ve all had those moments of doubt when listening to someone talk about how much power their car is making. The figure seems too high, right? So you question further and usually discover that they’re taking the factory-quoted power and adding X-amount of guesstimated power for whatever modifications they’ve performed — it’s a classic newbie move. The manufacturer is, of course, quoting engine power figures, measured at the flywheel using an engine dyno. As most will know, this doesn’t have much bearing on how much power is actually reaching the road, as a considerable amount of grunt is lost through the drivetrain before it gets near the wheels. Even though people always quote percentage of loss through a driveline — 2WD manual will lose 10–15 per cent, 4WD manual will lose 15–20 per cent, and so on — each vehicle varies substantially depending on its individual driveline. Further, as you increase the grunt, the drivetrain losses don’t necessarily increase at a constant rate. This makes any accurate conversion to a true flywheel power number difficult if not impossible. This is why it is so important to get a baseline figure on a dyno before you start any modifications or tuning. That way, when you gain power with your new upgrades, you’ll know exactly how much you have picked up. At the end of the day, no one likes it when people reel off half-cocked power figures — chuck the car on a dyno, then you’ve got the sheet to back up all that bragging!

Inertia v. Load Bearing

There are two main types of dyno design, and their use varies drastically.

An ‘inertia dyno’ is a form of rolling road; it is simply a large drum that the car drives on. Generally, these drums are quite large in diameter —1.5m or more — and they are damned heavy. By accelerating the drum with the wheels and applying some basic physics, the power produced by the engine can be calculated very accurately. The advantage of an inertia dyno is that it doesn’t have complicated power absorbers and this keeps the cost down. The disadvantage is that, with no power absorber, an inertia dyno is only any good for tuning at full throttle — great if you have a drag car but not so good for a street car.

A ‘load-bearing dyno’, on the other hand, includes a power absorber to apply load to the engine. This lets the dyno control wheel speed and hold the engine at a fixed rpm, regardless of the power. The power absorber may be a water brake, an eddy current, or hydraulic, depending on the manufacturer’s preference. These are the types of dyno that you need to tune every combination of load and rpm properly to ensure perfect drivability.

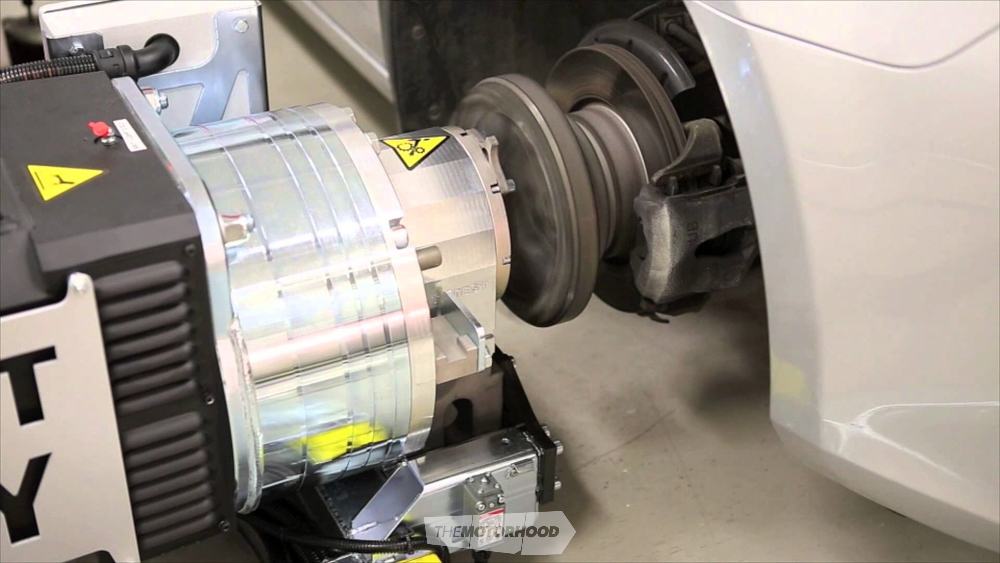

Rolling Road v. Hub

When getting your car tuned, you will come across two popular types of chassis dyno configuration. While everyone will have an opinion on which type of dyno is best, the truth is that both designs have pros and cons. The two types are hub dyno and rolling-road dyno.

A ‘rolling road’ measures the power directly off your drive wheels, so this, in effect, is what your tyres are delivering to the tarmac. Advantages include the ease of set-up, as getting your car on the rollers and running is very quick. However, a rolling-road dyno can suffer from traction issues with powerful cars. That is why you see videos of cars running on a rolling road with people sitting in the boot to help improve traction. Rolling roads are also sensitive to issues such as tyre pressure and temperature, and this can affect their power reading.

With a ‘hub’ dyno, the wheels are removed from the vehicle and a special adapter is bolted on in their place. The adapter is then located in the dyno pod, which includes the power absorber. Since the car is physically locked into the dyno, there is no chance of wheelspin. This also helps accuracy and repeatability run-to-run. Since the hub dyno measures power at the hubs, it often reads a little higher than a rolling road. The downside with a hub dyno is that it takes more time to get your car set up on it.

Smooth Operators

Aside from the hardware, the way the dyno is operated and set up can also influence the power reading. The power output will vary slightly in each gear, and generally the car is run in the gear that is closest to 1:1 — usually top gear in a three-speed or four-speed, fourth in a five-speed, and fifth in a six-speed.

Power-correction methods can also have a big impact on your results. The idea with power correction is to remove the influence of atmospheric conditions, such as temperature and barometric pressure. Every dyno manufacturer treats these parameters differently, and some modes produce more optimistic results than others. Less reputable dyno operators have been known to place the air-temperature sensor near the heat of the exhaust manifold to falsely skew the dyno results, so beware! If you are looking at upgrading your car and gauging the performance as you go, make sure you use the same dyno and the same tuner who uses all the same settings throughout the process, as that will give you most accurate representation of performance gains.

Geoffrey Moulton, at MCR Automotive, says:

“We can only work with what the customer brings us. Of course, we can spec and upgrade a combo to make power if that’s what is wanted, but most people want to bring a finished build to the dyno, and drive away with it tuned. The most common problems we face — especially with fuel-injected engines — are with fuel delivery and ignition. Someone may bring in a package that has the capability to produce a certain level of power, but does not have the appropriate supporting components. We see it often with fuel injectors that will reach 85 per cent duty cycle well before the engine starts producing the power the customer expects. With the injectors maxed, no further power can be made, and even less if the pump does not deliver fuel, or if there is ignition breakdown. We’ll do everything we can to get a safe tune, but it’s important to be realistic.”

Come Prepared

Although it may sound obvious, one of the most common complaints we hear from tuners is that customers may have all the good gear on the car, but they haven’t come prepared. Although it might not stop you getting a tune in the end, bringing the car in when it’s not at 100 per cent will cost you more money and time. Before booking some dyno time, make sure that you check the following:

- Are your fuel pump / injectors big enough to support the power you hope to make? What about voltage to the pump — is it as high as it should be? It would also pay to replace the fuel filter, especially if this hasn’t been changed in a while.

- Is your car leaking? This goes for both fluids and gases — at best, you’ll annoy the tuner, who has to clean up the shop floor afterwards; at worst, you’ll be sent on your way, especially if it’s an exhaust leak of some kind, which seriously affects the running of the car and renders a tune useless.

- Is everything tight and secure? Spend an evening going over your entire car to make sure that all the nuts and bolts are as tight as they need to be. Pay special attention to any areas that could suffer from a boost/vacuum/exhaust leak.

- Install a fresh set of spark plugs, gapped to what your tuner recommends for your application. Use the recommended heat range.

- Ensure that your engine has fresh oil, along with a new oil filter.

- Bring along a bottle of engine oil of the correct grade if top-ups are required during the tune.

- If your vehicle has more than 80,000kms on the clock, change the fuel filter — possibly to a high-flow unit if required.

- Ensure that you have a full tank of the fuel you plan on running for the tune. Use the fuel your tuner recommends for your application.

- If you have an airflow meter, ensure that the air filter you’re using is clean and not over-oiled.

- Make sure there is adequate tread on your tyres, and ensure that the drive wheels have similar tread depth.

- Do not turn up with semi- or full-slick tyres if your vehicle is getting tuned on a rolling road. The slicks will heat up and melt, sometimes sticking to the dyno. Road tyres are generally required.

- Check the tyre pressures — ensure the pressures are identical, or nearly so. Pressure test your intake system. If you’re wanting to run high levels of boost, we recommend using T-bolt hose clamps wherever possible.

- Check all of the boost/vacuum lines for leaks. This can have a serious effect on power levels. Cable-tie or correctly clamp all vacuum hoses and boost lines.

- Make sure your clutch is in good condition. With an increase in power levels comes more load on the driveline. A slipping clutch will set you back hugely.

- If you’re heading to a dyno tuner with a hub dyno, your wheels will need to be removed; ensure that you have your lock-nut key.

- Ensure that your boost control is correctly plumbed in and wired.

- Ensure that your turbo/supercharger is correctly installed. Make sure that oil-supply lines are tight.

- Ensure that you have a suitable port for an oxygen sensor, as wide-band sensors might be installed here for the tune.

- Ensure that the cooling system is in good working order. If your fans aren’t automatic, make sure you tell the dyno tuner.

- Provide the tuner with a written summary or list of modifications and engine specs, as this will be an easy reference and help decide a safe tune level.

- To prevent a big disappointment on the day, check that your engine-control unit (ECU) has not been password locked by a previous tuner.

- If you want the tune confirmed on the road after it has been dyno’d, ensure that the vehicle has a current WOF and rego. Some tuners will only drive a vehicle that is 100-per-cent legal.

A lot of being prepared comes down to doing the research beforehand — all the information is out there, and spending a few hours online and asking other enthusiasts will be a whole lot cheaper than your tuner spending a few hours rectifying avoidable issues. Fix these before going to the shop, as it could be the difference between getting a tune and putting the car back on the trailer and going home again.

Dave Heerdegen at Dtech Motorsport says:

“If you are starting a project or considering modifications, speak to your tuner beforehand, so they can give some advice and guidance around the best options and expected performance outcomes. Sometimes, when a vehicle is run on a dyno, the engine does not perform as expected, at which stage we’d spend some time questioning and diagnosing the cause. It may be as simple as the intake being too restrictive, or it might be that the engine is the wrong spec for its intended purpose. Please don’t bring a vehicle to the dyno that you would not be happy to take on the racetrack or on a long trip. Let the tuner know if there are any known issues or past problems, as it will save you time and money. Contrary to many myths, a dyno operator is not a magician — they don’t have X-ray vision, the ability to read minds, or enjoy guessing games.”

Glen Jennett at Engine Specialties says:

“People in general seriously underestimate the importance of tuning for any engine, whether it is standard or highly modified. Detonation from incorrect timing or fuel mixture can be terminal in just one loaded run in the car. The days are long gone where tuners run around on the street trying to tune cars. On any decent dyno, any car can be put under constant load at any rpm and monitored for detonation, fuel mixture, overheating, power and torque. If you are concerned about what may happen on the dyno due to someone else’s bad experience, then ask around and get feedback from other customers until you find a tuner you are happy with. There are many dyno operators around, so there’s a good range to choose from. But remember — it is not always about the final horsepower figure, as all dynos read differently. As that famous saying goes: horsepower sells engines, but torque wins races.”