data-animation-override>

“Sometimes nothing but the best will do. When Paul Kelly decided he wanted to build a new old race car, that was one of those times!”

The name Paul Kelly will mean different things to different people. Some will instantly recognize it as the name on a bunch of Christchurch car yards. Others will know it as the name that’s been seen on Porsche GT3 Cup race cars both here and in Australia. Of course, others will not have heard it before. If you fall into the third category, that’s all set to change.

As members of category one and two will attest, Paul Kelly doesn’t do things by halves, be it in business or in his passion for motor racing. His business acumen has seen him go from being a simple car dealer to running a string of yards and becoming a household name in the Christchurch region. Through this, Paul was able to pursue his passion for muscle cars, and more so for circuit racing, where he worked his way up to the ultra-competitive world of Porsche GT3 Cup racing. Not content with just winning events on local soil, Paul’s drive to win saw him cross the Tasman, where again he competed successfully, footing it with the big boys at tracks such as Bathurst, Eastern Creek, Phillip Island, and more.

Successful as he was in the Porsches, over the recent years Paul had started thinking more and more of combining his true automotive love — muscle cars — with his racing. Being one of those people who is annoyingly good at whatever he tries his hand at, he was never going to be content with just being a back-runner, or playing in a non-competitive class, yet he wanted to have plenty of fun, and race with like-minded people. This left him with one option, and that was Central Muscle Cars.

To make sure that his thoughts about CMC were correct, and to see if the class was all it was cracked up to be, Paul hired a first-generation Camaro off well-known race car builder Ken (Hoppy) Hopper. Of course, the chances of him not liking racing an overpowered, under-braked, muscle car against 20 or 30 similar vehicles was pretty damn unlikely. As you can imagine, he had a ball, and straightaway knew that he needed to get himself a more permanent piece of the action.

Being impressed with the build quality of the hired Camaro, Paul began discussions with Hoppy about getting something built in a similar vein — similar, except that, as opposed to the relatively simple Camaro, whatever car it was that Paul chose to race had to be built to his exacting standards. In terms of the performance of the car, its componentry, and its presentation, those standards were equally important . Race car it may be, but Paul’s a stickler for presentation, and the new car would be the pride of his collection, so it had to set the standard.

First came the crucial decision of what type of car to build. While the easy bet would have been a Camaro, the CMC series is fast becoming the Central Camaro Series, and building one that stands out is becoming nigh on impossible. It was with this in mind that Paul suggested a second-generation Firebird, as they share many components with Camaros of the same vintage, making parts readily available. Hoppy’s a bit of a closet Pontiac fan himself, so he jumped at the chance to build one. Of course, the fact that he’s built a number of second-gen Camaros, and knows them inside out, may also have helped — not that he’s incapable of building any type of vehicle for any type of class.

The hunt for a donor vehicle showed up a 1970 Firebird deep in the mid-western American desert. It was picked up for a bargain price. When you look at how little of that original purchase has been used, it’s apparent why there’s no need to spend big to begin with: little besides the bodyshell, glass, lights, and a few bits of trim has been retained.

With the car on its way from abroad, Hoppy got stuck into researching what parts were available that would be up to both his and Paul’s expectations, and set about ordering them. With Hoppy’s business, Ken Hopper Car Construction, capable of building all aspects of the car in-house, including CNC machining of custom components, the project became a giant jigsaw puzzle, as the parts came together.

The first step was constructing a serious roll cage in the freshly landed and stripped shell. Using his years of race car–building experience, Hoppy has made sure to stick to the letter of the class rules, yet ensure the shell is as still and safe as can be. While the welder was out, the rest of the bodyshell was reinforced wherever possible. Little care was taken with the front sheet metal though, as Hoppy managed to find a supplier of high-quality carbon-fibre replacement items. From the front nose cone, bonnet, and splitter, to the tail-light panel and boot lid, all are now carbon, a look that later in the build was carried over to the car’s interior. While the raw carbon looks amazing, as you see it here, Paul’s well aware that, no matter how well he drives it, sooner or later it’ll get a knock, and the carbon work will end up needing to be painted. That’s a risk he’s willing to take.

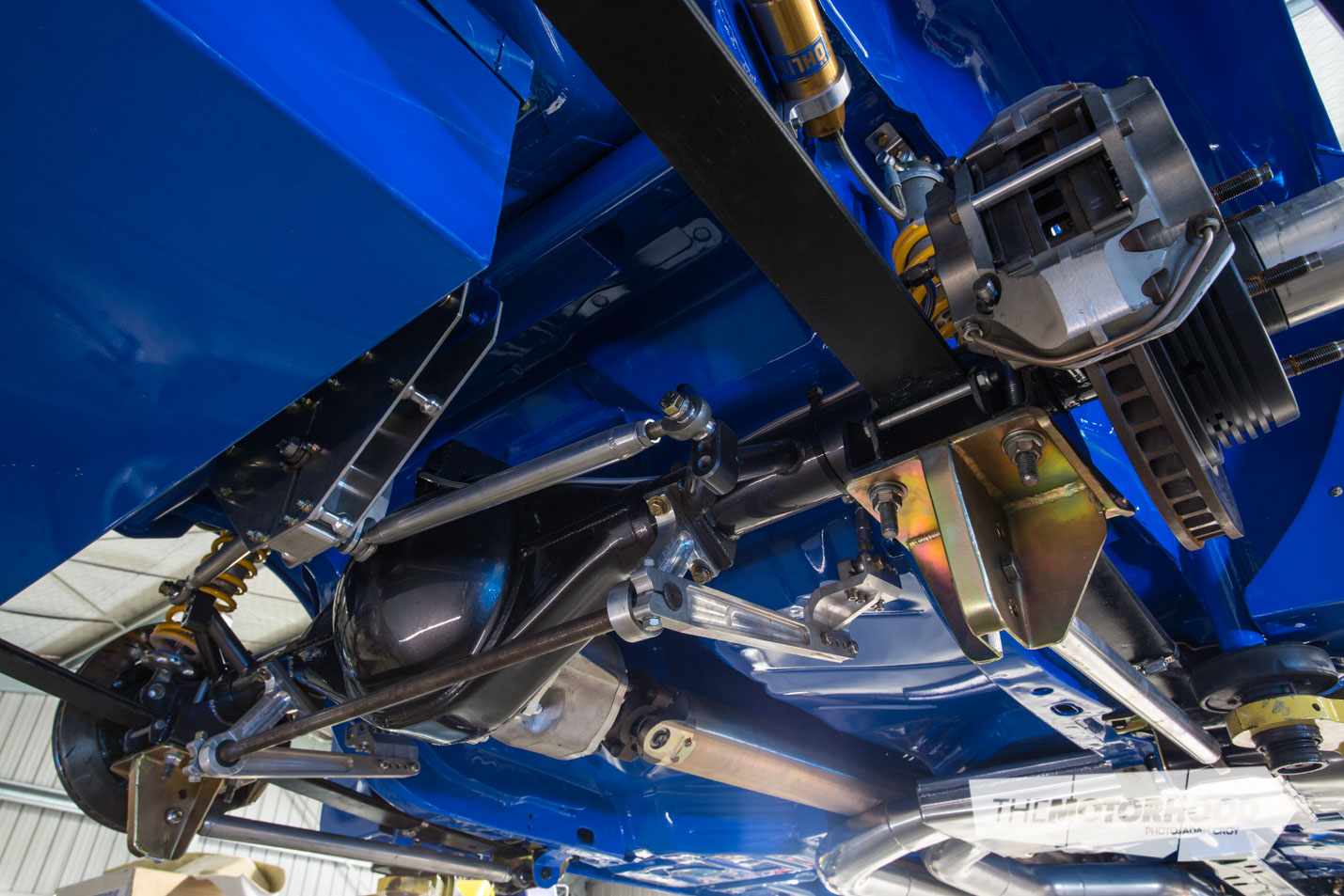

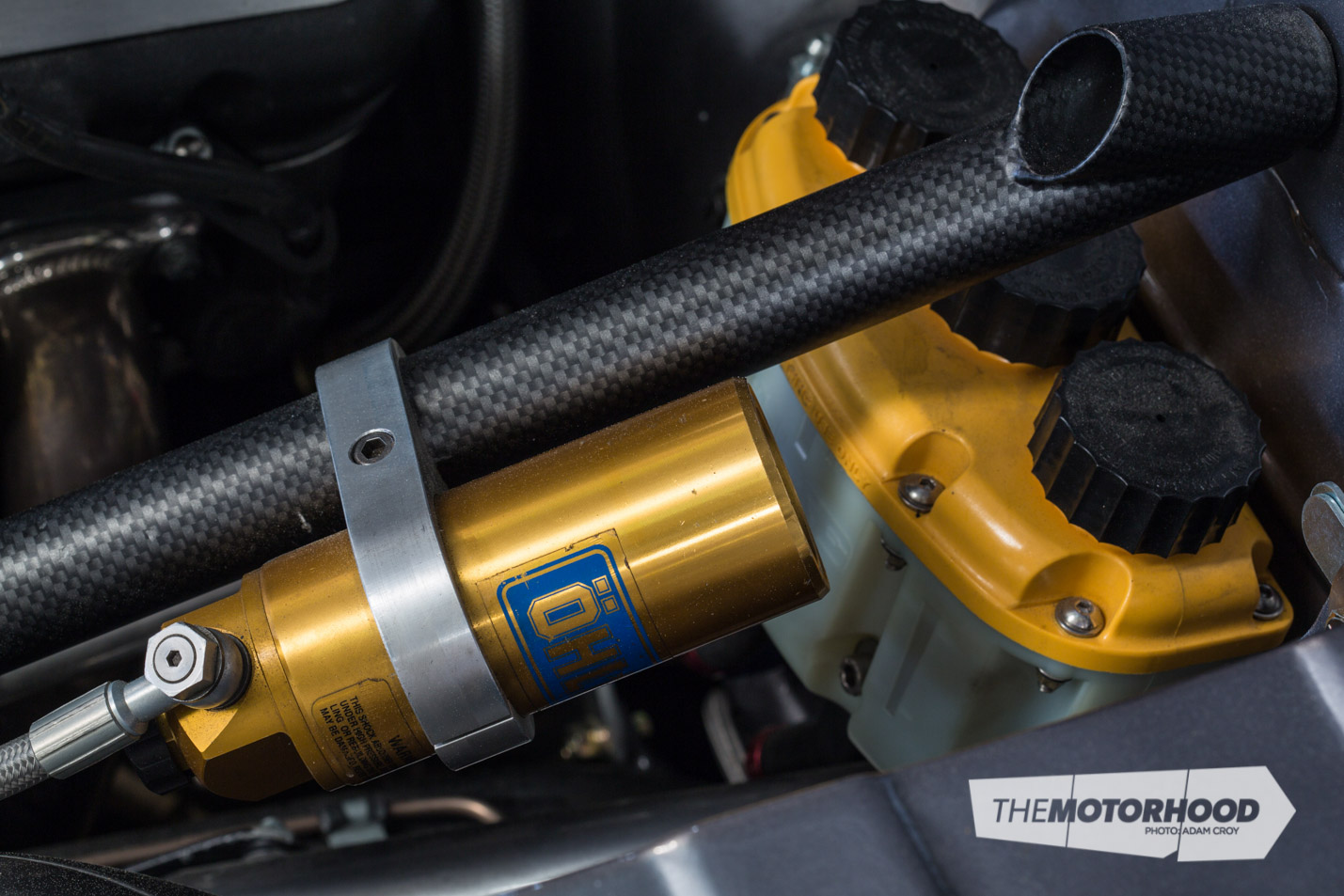

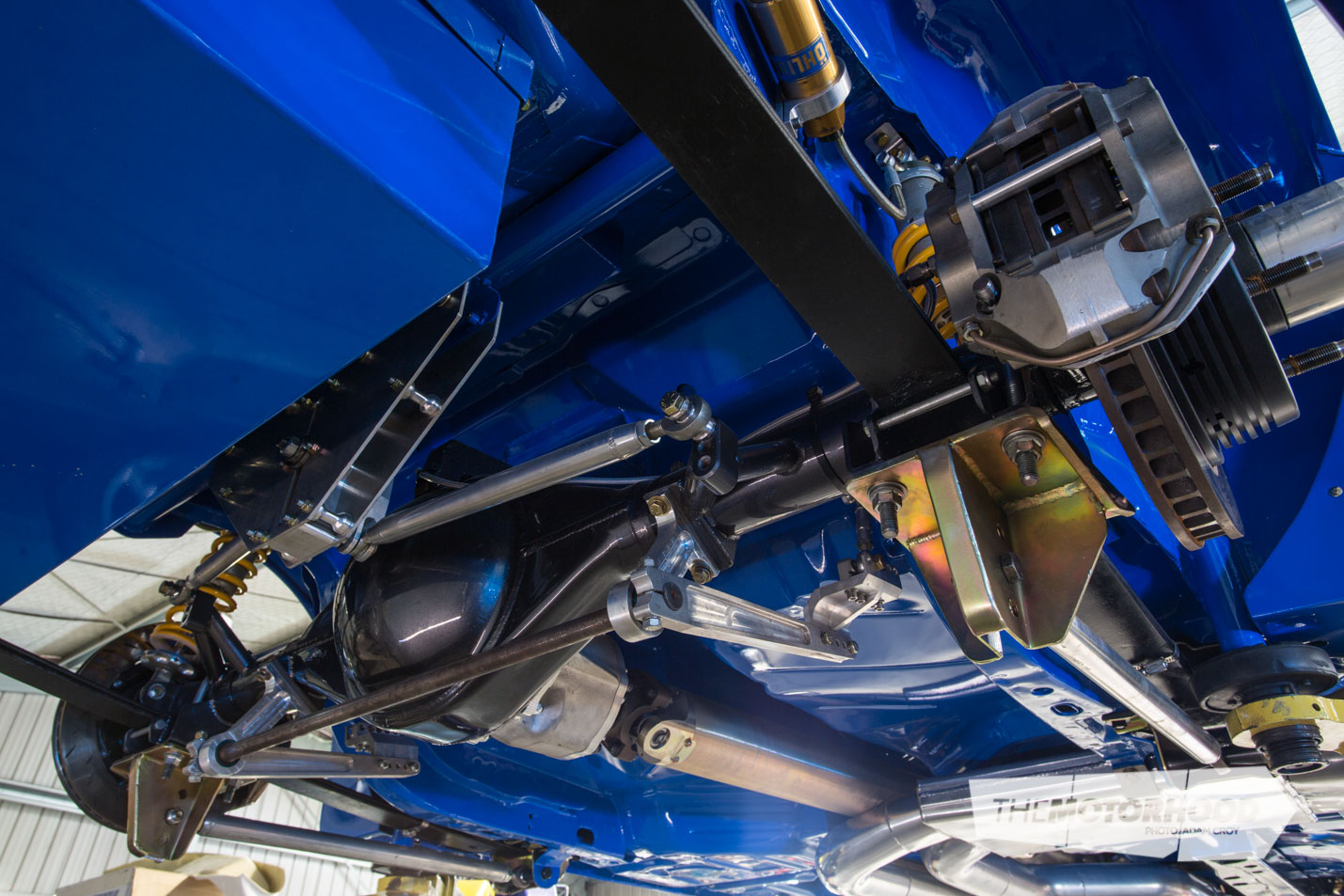

Before all the carbon work could be fitted and the car painted, the entire car was mocked up — even the impressive suspension and brakes. For these areas, Hoppy chose to run Ohlins canister-style coilover shocks with King springs all round, along with Global West front A-arms. Out the back is a class-legal three-link rear end created in-house by Hoppy and his team. To comply with class rules, leaf springs must remain in place — hence what may at first glance appear to be an odd arrangement of components. Finishing off the set-up are custom sway bars on each end.

For brakes, a set of Nascar-spec Brembo front calipers was selected and matched to 330mm rotors, while out the back AP Racing calipers were sourced to clamp 280mm rotors. It’s not just the diameter that’s impressive but also the thickness of the rotors. Both ends are fed instructions via a Triple Eight Race Engineering pedal box, from which Paul controls from his OMP carbon driver’s seat.

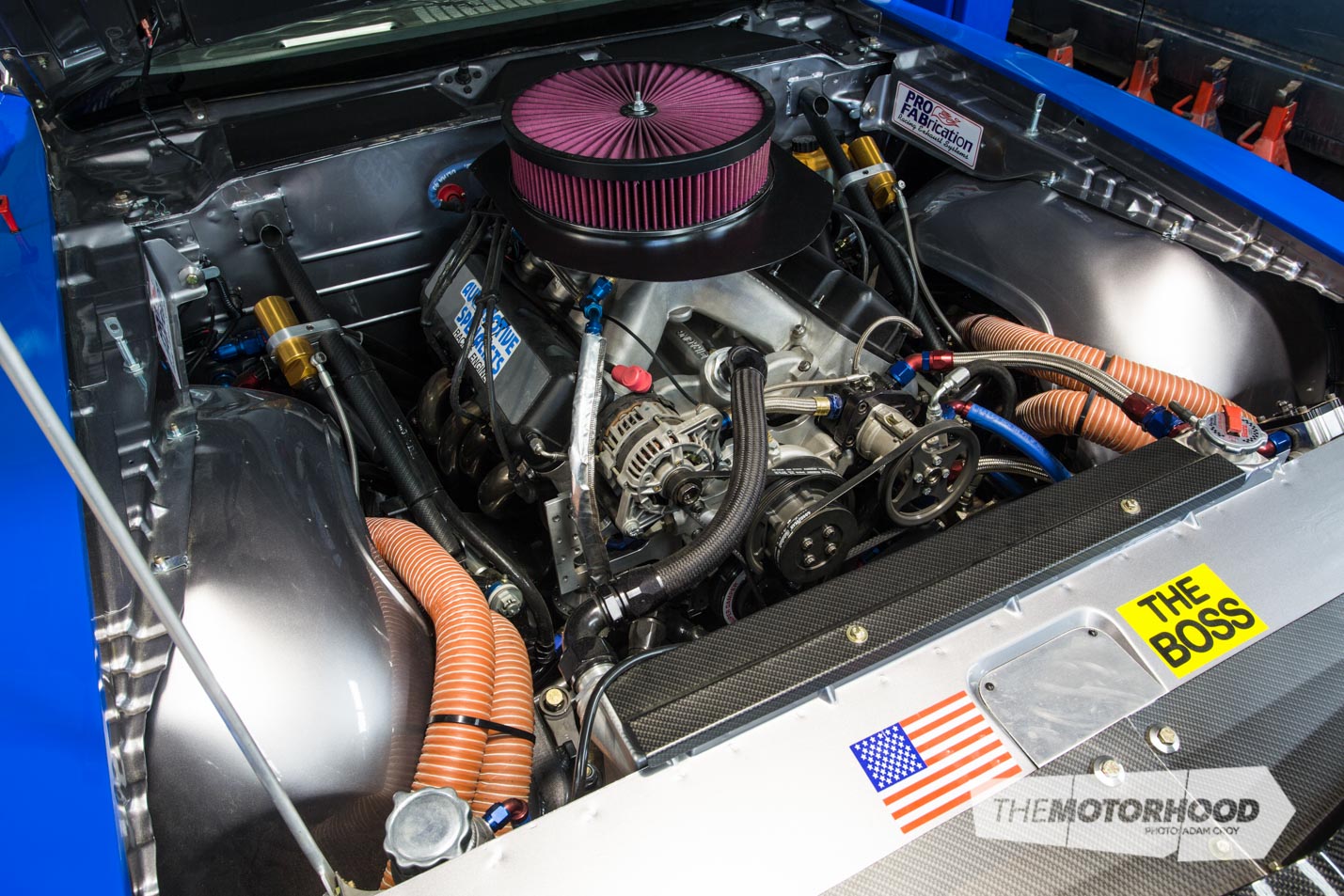

CMC class rules state that engines must be of factory origin and share interchangeable components, which, in a car like this, opens the door to SB2 Nascar spec engines, and that’s exactly what was selected. Rather than purchase a used combo, though, an engine for the car was custom built in America. It has a wider and lower powerband than what’s commonly available. This is set to allow the car greater exit speed from tight corners, as well as to provide the high-end brute grunt that’s needed at the pointy end of the field these days.

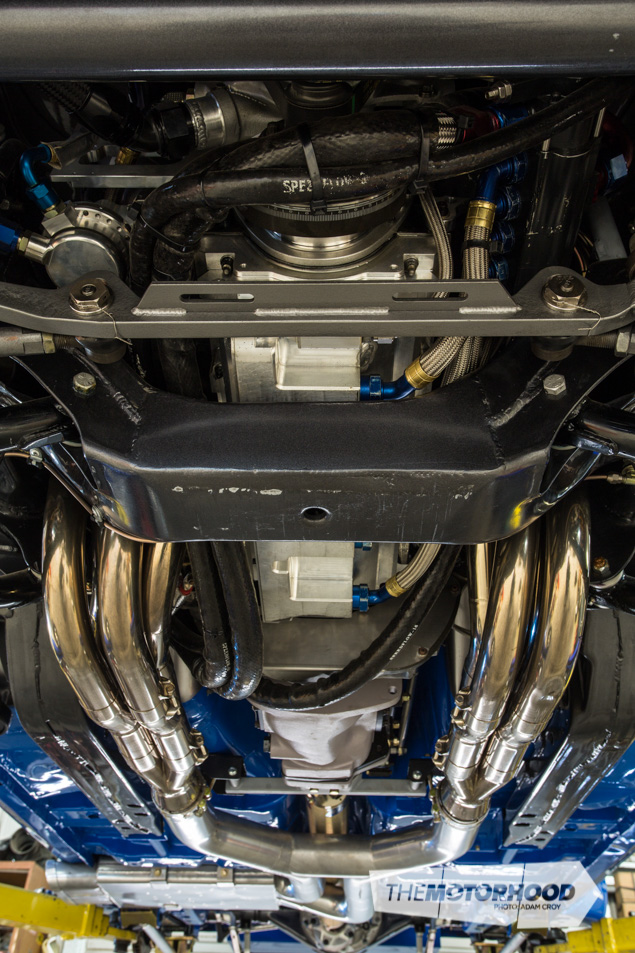

The high-spec motor is fed fuel from an equally impressive fuel system, yet for those who get a close look at the car, it’s the headers that draw more attention. Built by Profab Engineering to suit the engine and car combination, the equal-length pipes are a true work of art — then again, the whole car can be referred to in that manner, as, such is the quality, there’s not a single component that has been overlooked or skimped on.

For example, the driveline features a G-Force super-duty four-speed gearbox that sends power via a Tilton triple-plate clutch to a 9-inch sheet-metal diff fitted with a Truetrac centre, Speedway Engineering hubs, and CMS axles. As good as the suspension set-up may be, Paul still describes the car as like driving a La-Z-Boy armchair in comparison to the Porsche race cars he’s used to. Of course, part of that may be due to the class regulation Hankook Ventus tyres, which measure just 275mm wide. On a car like this, that is a very small footprint, especially when you’ve got a motor sitting up front that makes over 850hp. Luckily, having some tail-out fun and making a bit of smoke is all part of Paul’s plan, and part of what drew him to the class to begin with.

With the car ready just in time to tackle the first round of the 2014–2015 Enzed CMC series — as seen elsewhere in this issue — there’s been plenty of talk, especially amongst other competitors, about the potential of the car and driver combo. They all say that Paul will soon be one to watch. Judging from what we witnessed on the practice day, we’d say they’re right. Despite having had only a few minutes of seat time, Paul was already setting lap times not far off the front runners in the class. Sadly, a few unexpected engine issues saw him end up sitting most of the weekend out, but, as those who know Paul will attest, he’ll come back fighting harder than ever. If you’ve never watched a CMC round up close, there may be no better time than now, as things are about to get serious!

Specs

- Vehicle: 1970 Pontiac Firebird

- Engine: 398ci SB2 iron block, Bryant crank, Oliver rods, MAHLE pistons, SB2 Nascar heads, Jesel rocker gear, Holley intake, Crane dual-circuit Nascar distributor, MSD Nascar-spec ignition control, Profab headers, 3½-inch exhaust, SpinTech muffler, alloy radiator with built-in oil cooler, Carter electric lift pump (surge tank), mechanical fuel pump (carburettor)

- Driveline: G-Force super-duty four-speed, super-duty road-race ratios, Tilton triple-plate clutch, alloy 9-inch diff housing, 3.50:1 Truetrac centre, Speedway Engineering hubs, CMS axles, alloy Mark Williams driveshaft

- Suspension: Global West arms, Ohlin canister-style coilover shocks, King springs, three-link CMC-legal rear end, Ken Hopper Car Construction sway bars front and rear

- Brakes: Triple Eight Race Engineering pedal box, Brembo calipers (front), AP Racing calipers (rear), 330mm PFC rotors (front), 280mm PFC rotors (rear)

- Wheels/Tyres: Simmons FR 17×11 three-piece wheels, Hankook Ventus 275/40ZR17 control tyres

- Exterior: PPG Paul Kelly blue

- Interior: OMP carbon seats, Auto Meter gauges, long-style shifter, Ken Hopper Car Construction chromoly roll cage, factory dash

- Performance: 859hp at the flywheel

This article was originally published in NZV8 Issue No. 118. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: