data-animation-override>

“Airbrushing is a true art form, but have you ever wondered what goes into creating a great automotive work of art”

When we think of airbrushing, most of us think of some kind of creative artwork painted on the side of a car. Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, when vanning was all the rage, these large canvases on wheels provided the airbrush artists with plenty of space to create spectacular artistic artwork for all to admire.

Murals and flames were taken to a new level in the ’90s, with the airbrushing advances used to create shadows and shading on flames, to give an almost three-dimensional look. And murals moved away from the stencilled look to a more freehand style.

In recent years, the look of the traditional flame job has changed dramatically, thanks to the tribal style of flame and the introduction of ‘true fire’ — a look that resembles exactly that; true fire. The creation of true fire revolutionized the entire industry, making it a highly sought-after technique and effect.

The creator of this effect, Mike Lavallee of Killer Paint, hails from Snohomish, in Washington, USA. He runs a very successful business applying his skills to whatever his clients require. This can be anything from helmets, fridges, and bonnets, right up to full vehicles. Mike also travels the world, teaching his skills to other airbrush artists. While he was on a recent trip to Christchurch, we were invited into the booth to witness Mike weaving his magic on Amber Raudon’s ’26 Essex. Here’s what we saw:

Step one:

Once the car has been prepped and rolled into the booth, Mike likes to walk around the car to visualize the layout for the graphics. Because each car is different, Mike says that the car itself suggests how it would be best to lay the graphics out.

Step two:

Once he has the idea in his head, Mike starts laying out the tape. This can be a time-consuming process, but it is this point that is make or break. If you get it wrong here, the overall look won’t be pleasing to the eye, and certainly won’t complement the shape of the vehicle.

Step three:

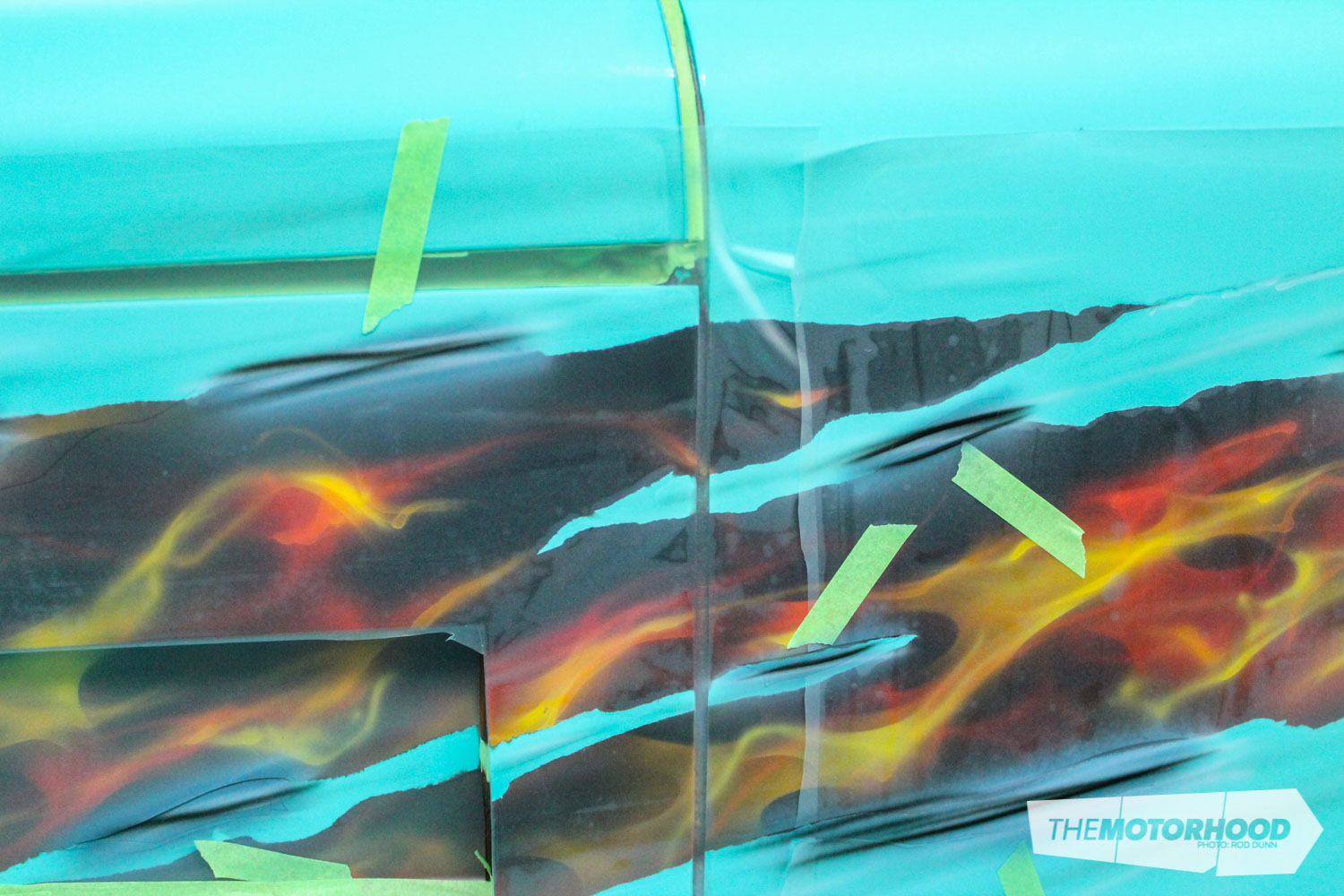

Mike decided to go with the look of metal tearing away, exposing the fire beneath. To create the jagged edge of ripped steel, the masking tape is applied, then torn lengthways to give the rough edge that he is after. The rest of the vehicle is then covered to avoid overspray.

Step four:

Mike moves into the mixing room and prepares all of the paint for the job. In this case, he prepares a range of solid colours and candies that were mixed from DNA Custom Paints — an Australian-made product.

Step five:

Now that the paint has been mixed, Mike starts applying black paint, to give the fire a dark background, and to also make it appear as though the fire is coming from within the engine bay.

Step six:

Starting with the darkest colour, red, the first of the flames is applied. It is at this stage that it helps to know how the end product will look, as the red forms the base for the other colours to flow over. Having been doing this work for many years, Mike makes it look easy.

Step seven:

After the red has been applied, the flames are lightly coated with red candy, which helps the fire to ‘pop’.

Step eight:

Orange fire is now added freehand. Once completed, it is also coated with candy — in orange this time.

Step nine:

Mike now starts adding the yellow, using both a stencil and his freehand technique. It is at this point that the flames start to take on a realistic look.

Step 10:

Once that is done, Mike hits the yellow with a coat of orange candy. In this photo, you can see the difference between the area that has had candy applied, and the area that was still to be done.

Step 11:

After Mike applies more yellow fire, the flames are coated in yellow candy.

Step 12:

Now we can see the true fire coming alive. With the application of so many different layers, spray dust can become an issue, so Mike uses a tag rag between each colour to ensure that all dust is removed.

Step 13:

Once Mike has finished with the colour and has given the car the once over, the graphics are unmasked to reveal the fire.

Here’s how it looks unmasked.

Step 14:

To give the impression that the metal has torn, causing it to ripple, Mike adds some shading.

Step 15:

After applying some low-tack clear-application tape over the fire, Mike marks out where the metal shreds, or folds, are going to be, before cutting them out with a sharp blade.

Step 16:

The paint is now applied to the cut-outs to give the impression of light hitting folded-back steel. The tape on the clear film helps Mike locate the cut-outs, as they can be hard to see.

This is the end look, once the film has been removed and some shading applied.

Step 17:

Once the final touches are done, the car is clear coated — in this case, by Robert Duff from the Southern Institute of Technology, who helped Mike prep the car. After a good cut and buff, the car will be ready to be picked up.

There you have it. After a day in the booth, another work of art hits the street — created by a true master. If you think your ride could be taken to the next level with some airbrush art, why not check out the local talent in your area. Who knows, it could be your ride gracing the streets and looking like it’s on fire!

Pick up the issue of issue of NZV8 that this article was first published in: