data-animation-override>

“Eight-inch, nine-inch, 10-bolt, 12-bolt — what does it all mean? What should you look out for? We’ll answer those questions in Part I of our two-part diff buyer’s guide”

Every single car has a diff of some form, and, while names are bandied about the whole time, the technical make-up of diffs is somewhat less known, as is what to look for when you’re looking at buying, upgrading, or repairing one of your own. Over the next few pages, we aim to help buyers know what they’re looking at — be it at a swap meet or brand new in store.

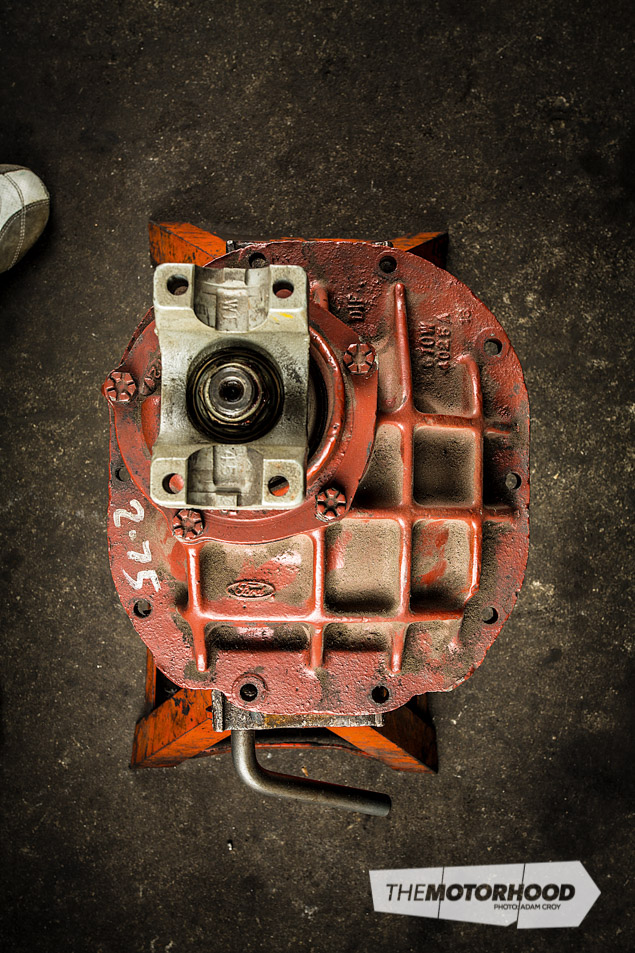

Ford nine-inch

Ford nine-inch diffs are the most well known to V8 lovers and hot rod builders. First introduced in 1957, they’ve become the mainstay for car lovers around the globe. With their dropout centre-section design, high-hypoid gear cut, and pinion-nose bearing, they’re an extremely reliable and strong rear end. With all the different versions, plus a number of aftermarket options now available, it pays to know what you’re getting into when buying one.

The simple thing to note about nine-inch diffs is that they have no bolts on the rear cover. The term ‘nine-inch’ refers to the outside diameter of the ring gear, and the head is held in from the front by 10 bolts.

The first generation of nine-inch diffs is identifiable by the two dimples on the rear cover, a fill plug, and a round shape with very little triangulation from the centre section down to the axle tubes. Be careful, though, as some Ford eight-inch diffs also have the two dimples. The best test of a nine-inch is to try removing the two lower carrier case bolts. If you cannot fit a socket onto these two lower bolts because the carrier is in the way, it’s a nine-inch.

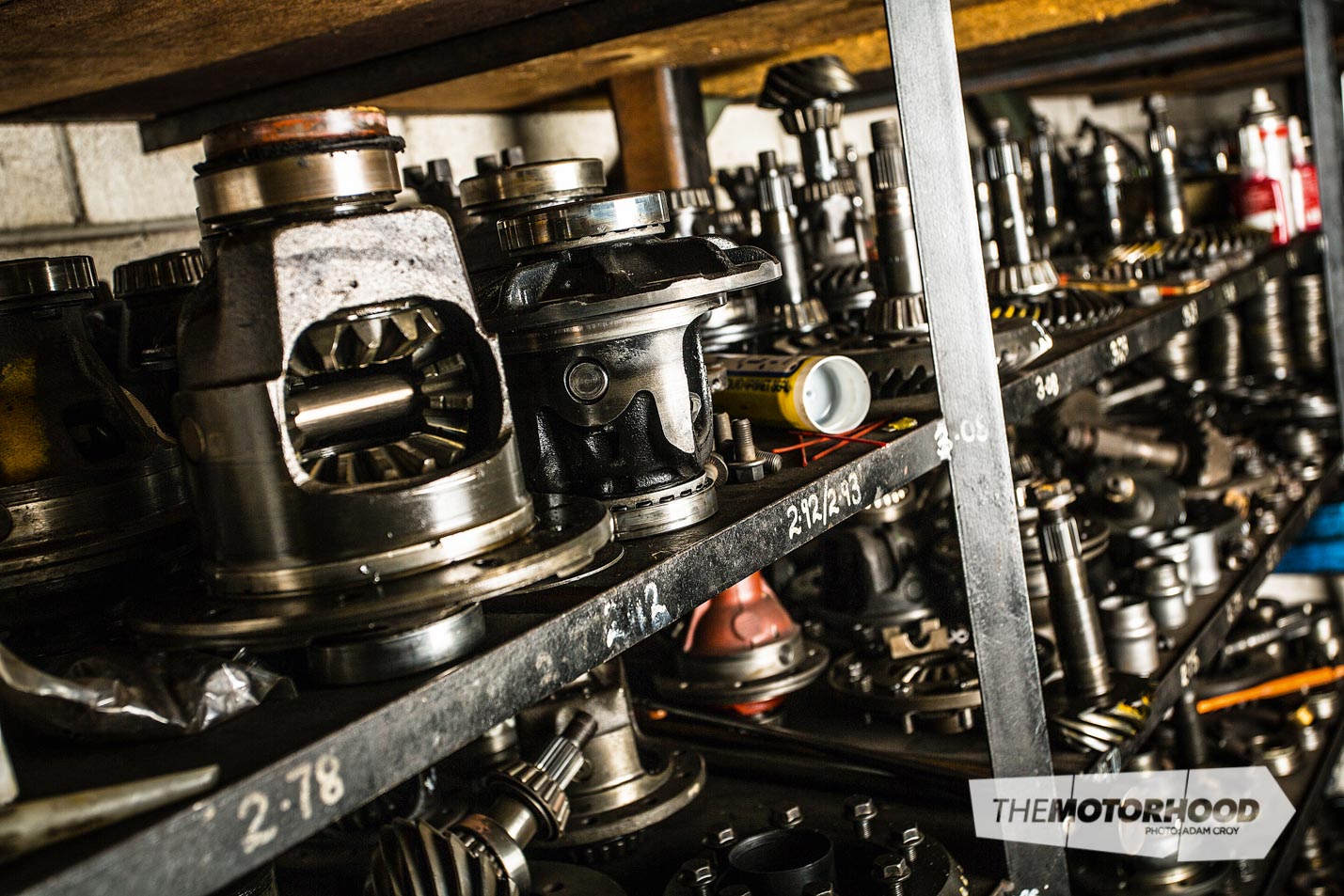

Part of the reason for the popularity of the nine-inches is that these diffs have a removable carrier, which allows for a quick rear-end change. Another advantage is that all the carriers are the same, so you can use just about any ratio without the added cost of purchasing a larger carrier assembly for larger ratios. Ratios available range from 2.50:1 through to 6.50:1. While the first generation was offered with both a conventional open carrier and an Equa-Lok limited-slip carrier, many of the ’73 and later pickup-sourced diffs also had a limited-slip known as ‘Traction-Lok’.

These days, you’ll struggle to find one, but Ford attached an aluminium tag to one of the carrier bolts at the factory to aid in determining the gear ratio and build date. The tags feature two rows of numbers; the first has five digits that designate the part number for the axle, while the second row has nine or 10 digits, the first three indicating ratio, such as 275 for 2.75:1 or 2L75 for a 2.75 Positraction. The middle three numbers indicate the production date, and the last three digits indicate the factory at which it was produced.

Nine-inch diffs came with either 28-spline or 31-spline axles, both of which are held into the axle tube via a flange outboard of the axle bearing and seal. For strength reasons, the 31-spline version is the one that most people look for, despite the 28-spline version being easy to modify to accept the stronger 31-spline axles. On pre-1972 diffs, it is possible to shorten the 31-spline axles to accommodate narrower wheel tracks. However, 28-spline axles and axles from post 1972 diffs cannot be easily shortened, as they are tapered. The axle tubes in this first generation were simply butt welded to the centre section, meaning that they were not as strong in high-horsepower applications.

The second generation was very similar to the first, with the dimples and fill plug, but the axle tubes are a lot better mounted, thanks to the way the centre section flows down to the axle tubes. This generation of nine-inch is the most common and is often used in high-horsepower builds.

In 1977, Ford refined the design once again, losing the twin dimples and changing the shape of the rear cover to include a bulge for the crown wheel. This generation is highly likely to come with larger axle bearings, which many people prefer over the earlier versions. However, if all you can find is a small version, it is possible to fit the large bearing tubes.

There are several strength ratings for nine-inch diffs, depending on the donor car. The 1967–1973 Mustangs used the thinnest tubing, while 1957–1968 full-size passenger cars (such as the Galaxie) and half-ton pickups came with what’s considered to be a medium-duty option. The 1971–1976 Ranchero and Torino came with what’s often thought to be a race-ready, high-performance unit straight from the factory. Likewise, 1969–1977 full-size Fords, Mercurys, Lincolns, and 1973–1986 pickups used the strongest (thickest tubing) housing of all the nine-inch diffs. It’s in these variants that you’re likely to find the 31-spline axles.

Flange-to-flange dimensions range from 57¼ inches right through to 68 inches, so, with a bit of hunting, you may be able to find one for your vehicle that requires no modification.

Expert’s Opinion

Lee from Diffs R Us says: “These days, thanks to the internet, a nine-inch is no longer the only option, as so many parts are available for a wider range of diffs. The nine-inch, though, is probably the most adaptable diff to fit into anything. With the supply being limited, grab what you can, as there’s not a lot out there for sale and the prices vary hugely.

“Most of the ones that come into the country now are ’70s and ’80s stuff, and a lot of it really is just old, worn-out junk. So you’re buying a whole lot of parts. More and more guys are looking at buying drum-to-drum or disc-to-disc, all brand new. Price-wise, this could set you back up to around $6K. Unless you’ve had the components lying around for ever, as a lot of hot rodders do, there’s no cheap way of doing it these days.

“Some people complain that a nine-inch robs power, but that’s where it gets its strength, as the total surface area of the gears is probably 25–30 per cent larger than that of any other style of diff out there of equivalent size. It’s got nothing to do with the axles or spider gears.”

You can see what Lee is talking about when comparing BorgWarner and Ford nine-inch crown wheel and pinions.

Countless people have been caught out by the not-so-common 93⁄8-inch Ford diff and think they’ve grabbed a bargain. These came out in some ’60s Ford Galaxies and similar and are identifiable only by their one curved rib [visible as the lower lateral rib curves upwards towards the upper rib]. If you’ve got one like this, it’s not a nine-inch, and it has no interchangeable parts with one, rendering it virtually worthless.

Ford eight-inch

A good budget alternative to the Ford nine-inch — if you’re not making huge horsepower — is the Ford eight-inch. As it is slightly less popular, more options are available, and at a lower price. Like the nine-inch, the Ford eight-inch has a dropout centre section consisting of the diff centre and the carrier. Like many of the nine-inch options, the eight-inch uses 28-spline axles, so it’s a good, strong unit and easy to service.

Ford first used the eight-inch in 1962 and continued to use it in many vehicles fitted with a small block V8 or six-cylinder up until 1980. While it’s most commonly thought of as the diff from the 1965–1978 Mustang, it was also found in a range of other models, meaning that there’s a variety of widths available between 56 and 62 inches.

The easiest way to identify an eight-inch is that, like the nine-inch, there’s no removable rear cover; then, if you can put a socket onto the lower mounting bolts, it’ll be an eight-inch, as the socket will not fit on a nine-inch, as mentioned on the previous page.

If you’re lucky enough to find one with an ID tag still attached, then you’re in luck. Axle codes will be either a four-digit or five-digit letter designation on the top row of numbers; the second row of numbers indicates the ratio, date of production, and casting number. The first number in this row will be straightforward: a 279 means a 2.79:1 ratio, and so on. The letter ‘L’ between the first two digits means that the diff was fitted with an Equa-Lok or Traction-Lok from the factory, e.g. 2L79.

In terms of case and spring strength in the limited-slip differential (LSD) itself, the post-1967 Traction-Lok units are more desirable than the pre-’67 Equa-Lok versions. The way to tell if an eight-inch is pre or post 1967 is to examine the case. A pre ’67 has only horizontal ribs on the case as well as a drain plug on the rear. Post ’67 items have a fill plug added to the carrier itself, and the rear housing has no filler hole. Carriers from ’67 onwards had vertical ribs added to better reinforce the carrier assembly. The axle tubes on the early rear-end assemblies are also tapered as they approach the backing plate, whereas the newer axle tubes are a consistent diameter from centre carrier to axle flange.

Original ratios range from 2.79:1 through to 5.43:1, but, due to their popularity, there’s a wide range of aftermarket items available. Just like the nine-inch, the eight-inch uses no carrier breaks, meaning you can put a 5.43:1 ring-and-pinion in a 2.79:1 rear without changing to a smaller carrier.

Some eight-inches came with tapered axles, which makes shortening them impossible, while others came with non-tapered ones, which are easily modified. The other thing to look out for is that two different pinion lengths were produced — a 3½-inch and 4½-inch.

The axle bearings used in the Ford eight-inch are heavy duty and long lasting. However, the oil seal behind them does degrade and need to be replaced, and the bearing has to be destroyed to remove it. Without the use of aftermarket parts, it’s advisable to run an eight-inch only if you’re making 300hp or less. Therefore, if you think you’ll upgrade your engine later on, an eight-inch may not be right for you.

Expert’s Opinion

Lee from Diffs R Us says: “Go back 20 years, and everybody ripped them [eight-inch diffs] out and fitted nine-inch centre sections. But these days you don’t need to. Unless you’re making huge power, that little eight-inch works perfectly fine.

“There’s not a lot out there for sale, so you’re buying what’s left. Most of the guys playing with eight-inch diffs own early Mustangs. The days of people buying an eight-inch to fit in their hot rod because they were the right width have ended, as there’s just not enough of the diffs around.”

Chrysler 8¾-inch

Original equipment on many Chryslers from 1957 through till 1974, the 8¾-inch diff is the Mopar equivalent of the Ford nine-inch. These remarkably strong diffs have a removable carrier, which, like the nine-inch, unbolts from the front. Due to the length of time they were produced, there are various 8¾-inch options, some having pinion shafts with a larger diameter and some coming with various limited-slip heads.

Depending on the year, the pinion shaft can be from 13⁄8 inches in diameter up to 17⁄8 inches, with the largest pinion used in the later model and heaviest-duty muscle-car applications.

If you’re lucky enough to find an ID tag, it will clearly identify the ratio. If the ratio is followed by an ‘S’, that indicates that a Sure Grip (LSD) head is fitted. The only year the Sure Grip option wasn’t available was 1957. However, two versions were offered from 1958 to 1969. From 1969 onwards, some units used a BorgWarner spin-resistant cone clutch system, which is better still.

Casting numbers 2881488 and 2881489 were used from 1969 to 1974, and indicate the most popular unit for conversions, due to their running the 17⁄8-inch diameter pinion shafts.

It’s important to note that those sourced from Chrysler A-bodies use a 5×4-inch–PCD stud pattern, while all others use a 5×4½-inch pattern. Due to their wide range of fitments, widths vary from 57¹/8 inches through to 64³/8 inches, and spring pads range from as narrow as 43 inches to 47½ inches but are easily moved if required.

Many ratios were available, with the most common being 2.76:1, 2.94:1, 3.23:1, 3.55:1, and 3.91:1, although, since the 8¾-inch was also fitted to Dodge pickups, there are ratios as tall as 5.57:1. As with the nine-inch, there are no carrier breaks, so any ring-and-pinion combo can fit without changing the carrier. Another advantage is that the Sure Grip head can be installed with no other changes required.

Those 8¾s produced before 1964 featured tapered axles, and the axle-flange assemblies were held in place by the use of a key and locknut configuration. Later versions used flanged axles with a pressed-on axle bearing and loose retainer, allowing for slight adjustments in width to be made by use of an adjustable bearing flange used on the passenger-side axle. The later model C-body and truck-sourced axles are the longest and the only ones that can be cut and re-splined due to them not being tapered.

Expert’s Opinion

Lee from Diffs R Us says: “When looking for this type of thing, people learn really quickly how much America has changed, as they’re just not available any more. When scrap got to $800 a ton, a lot of stuff got scrapped. And all the good stuff, such as parts from the muscle-car era, is just too expensive, because all the guys looking for matching-numbers parts will pay the money for them. Because of this, new parts have become cheaper than good original parts.”

Dana series

Despite being associated with Mopar, the Dana series actually comes standard on various pickups from GM, Dodge, Chrysler, Jeep, and Ford, so there are plenty of different options. The high-strength Dana 60, as used in many Mopar muscle cars, can be identified by its straight axle tubes, 10-bolt asymmetrical cover, and the number 60 cast into the housing.

A range of axle spline options is available — 16, 23, 30, 32, 33, and 35 — and ratios tend to vary from 3.31:1 to 7.17:1.

The next step down from the Dana 60 in terms of strength is the Dana 44, which was available in many passenger cars and 4WDs from the mid 1950s through to 2010. Dana 44s have 9⅜-inch cases and 10 bolts holding the rear cover in place, and the original ring-and-pinion gears were produced from strong steel, making them capable of handling high horsepower. Although not quite as strong as the Dana 60, the Dana 44 is also a lot lighter. Axle shafts are 1⅛ inches in diameter with 30 splines. Two separate carriers are needed, depending on what ratio you wish to run. Any gear size from 2.72:1 to 3.73:1 will use one carrier; gears from 3.92:1 up to 5.89:1 use another.

Those sourced from passenger cars will have equidistant axle tubes, while those from 4WDs will be offset and therefore only of use in aftermarket applications if they are going to be narrowed.

Due to the huge range of vehicles to which these diffs were fitted, it’s essential that you check the wheel stud pattern when looking to purchase one. Because of the popularity of these diffs, most replacement parts are still available, as are a wide range of aftermarket items.

Interestingly, the Dana 44 was also produced in an independent-rear-suspension (IRS) variant and was supplied as original equipment from the manufacturer in cars ranging from Corvettes and Vipers right through to Jaguars. Often referred to as the ‘Dana 44 ICA’ or ‘Dana 44 IRS’, standard 8.5-inch Dana 44 ring-and-pinion gear can be used in the IRS model but only through the use of a special installation kit that includes special shouldered bolts to mount the standard ring gear to the IRS carrier and a special pinion bearing set.

Expert’s Opinion

Lee from Diffs R Us says: “You can get a lot of brand-new parts for these, and they’re a strong unit, as they’re built for trucks. The parts can be a bit expensive, though, due to supply and demand.”

Jaguar

Due to their all-in-one nature, and for ease of installation, Jaguar rear ends have become a common fitment in many hot rodding applications. The actual diff itself is a Dana 44, although produced by Salisbury, which is a subsidiary of Dana Corporation. Jaguar first used the Dana 44 for the Jaguar E-Type in 1961, and continued to use it right through to 1996, although one variant was used by Aston Martin until 2004.

The assembly was manufactured in three sizes, with differing track widths to suit different vehicle sizes — 50 inches, 54 inches, and 58 inches. Final-drive ratios range from 2.88:1 to 3.54:1, depending on the Jaguar model. Limited-slip heads were standard in some models and factory on others.

In 1986, the second generation came into production — with a differently mounted carrier — and is recognizable by its more triangular-shaped subframe and lack of radius arms.

It’s worth noting that some Jag rear-end assemblies come with a splined stub axle for knock-off wheels and others with a five-stud arrangement. Some models were also fitted with a sway bar.

Until 1993, the brakes were inboard mounted. Then, from 1993 to 1996, the brakes were outboard mounted. When purchasing an inboard-braked set-up, take a look at the seals near where the inboard calipers are mounted, as overheating from the brakes has always been an issue with this design; however, parts are readily available. Most car builders agree that these rear ends are good for up to 500hp.

Expert’s Opinion

Lee from Diffs R Us says: “These drive nicely, and do everything right. However, when it comes to fixing them, it’s an expensive exercise, because, when they need an overhaul, you have to fix the whole lot. Then, if you want a limited-slip for one, you’ll need to buy original equipment. So you’re stuck with using old parts. They do look good under a hot rod, but you’ve got to be a pretty dedicated hot rodder to use that system.”

Check back here for Part II, where we’ll be finding out more about GM 10-bolt and 12-bolts, Holden Salisbury, BorgWarner (Commodore), Hilux diffs, and more.

This article was originally published in NZV8 Issue No. 112. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: