data-animation-override>

“Chances are you’ve either heard of metal spinning or seen the result, but, till now, never thought about the process behind this dying art form”

How many of you have been to a car show and admired a great set of bullet hubcaps, or seen a nice set of triple oil-bath–type air cleaners on a feature car and wondered where the owner got them from? Chances are, they were either bought as a mass-produced product over the counter from a speed shop, or they were custom made for the car by one of the handful of highly skilled metal spinners in this country.

What is ‘metal spinning’, you might ask? Well, there are basically two types: spinning on a machine, such as a CNC lathe, or hand spinning, which is becoming a dying art and is very popular among the custom and hot rod crowd. One of the advantages with this second type of spinning is that you can get custom parts done, even if you only require one, at a really good price.

To get the low-down, we enlisted the help of the man who’s undoubtedly New Zealand’s leading metal spinner in the hot rod and custom car scene — Phil Hutty. Phil runs his business, Metal Spinning Specialists — often referred to as ‘Spun By Hutty’ — from his home workshop in Oxford, North Canterbury, yet ships parts to customers all around the globe.

Phil first found out about metal spinning as a teenager, when he had some work experience in a workshop with a mate. When his mate went overseas, Phil followed, but came back a few years later. One day, while talking to his mate’s old boss and finding out that he was still looking for a metal spinner, Phil decided to give it a crack — and, as they say, the rest is history.

Most of Phil’s work is in the automotive field, with ram tubes, velocity stacks, air cleaners, wheel and headlight trims, the very popular bullets, and the like. That’s not to say the technique can be used only in the automotive realm. An endless list of items can be created using metal spinning — among them, things like urns, cookware, and gas cylinders. It also has plenty of architectural uses.

The process is most easily described as pressure being applied to a sheet of metal spinning over a formed buck (mould). It sounds simple, yet it is an art form, requiring a steady hand and attention to detail.

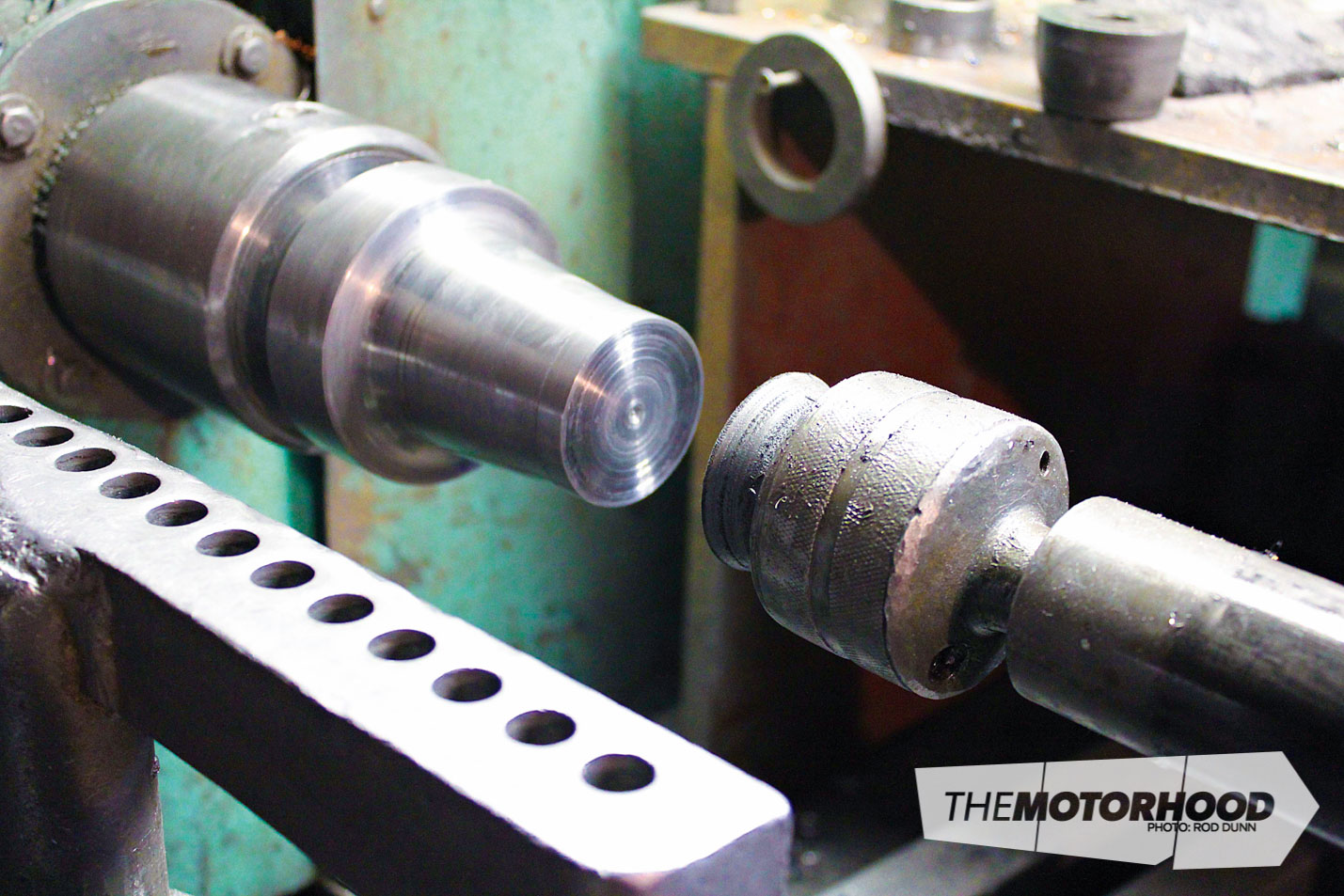

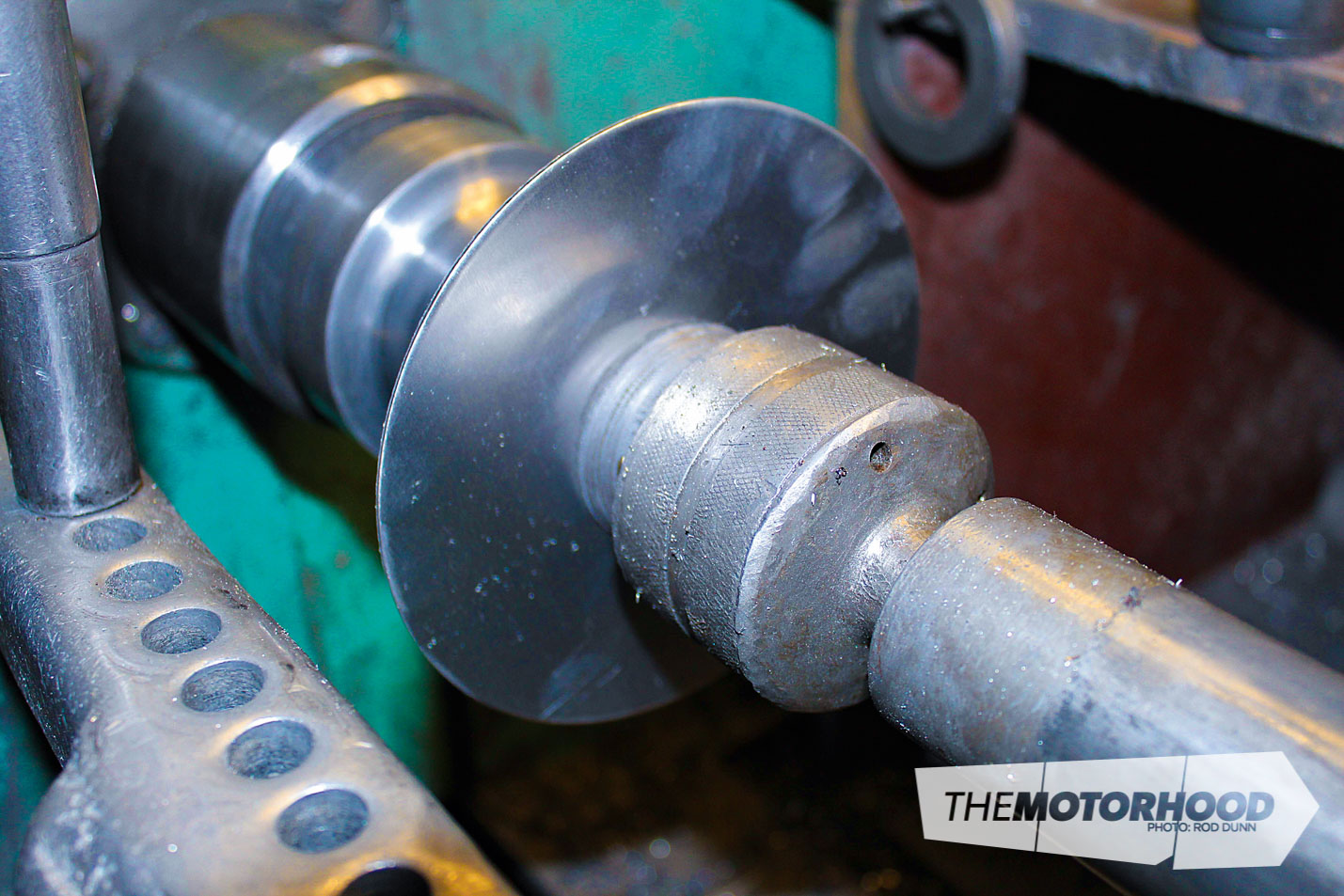

The first step to making any type of metal-spun product is to make sure the correct formed buck is mounted in the drive section of a lathe. The form block can be made from steel, but Phil has also used wood and plastic, which have done the job just as well but don’t last as long as steel.

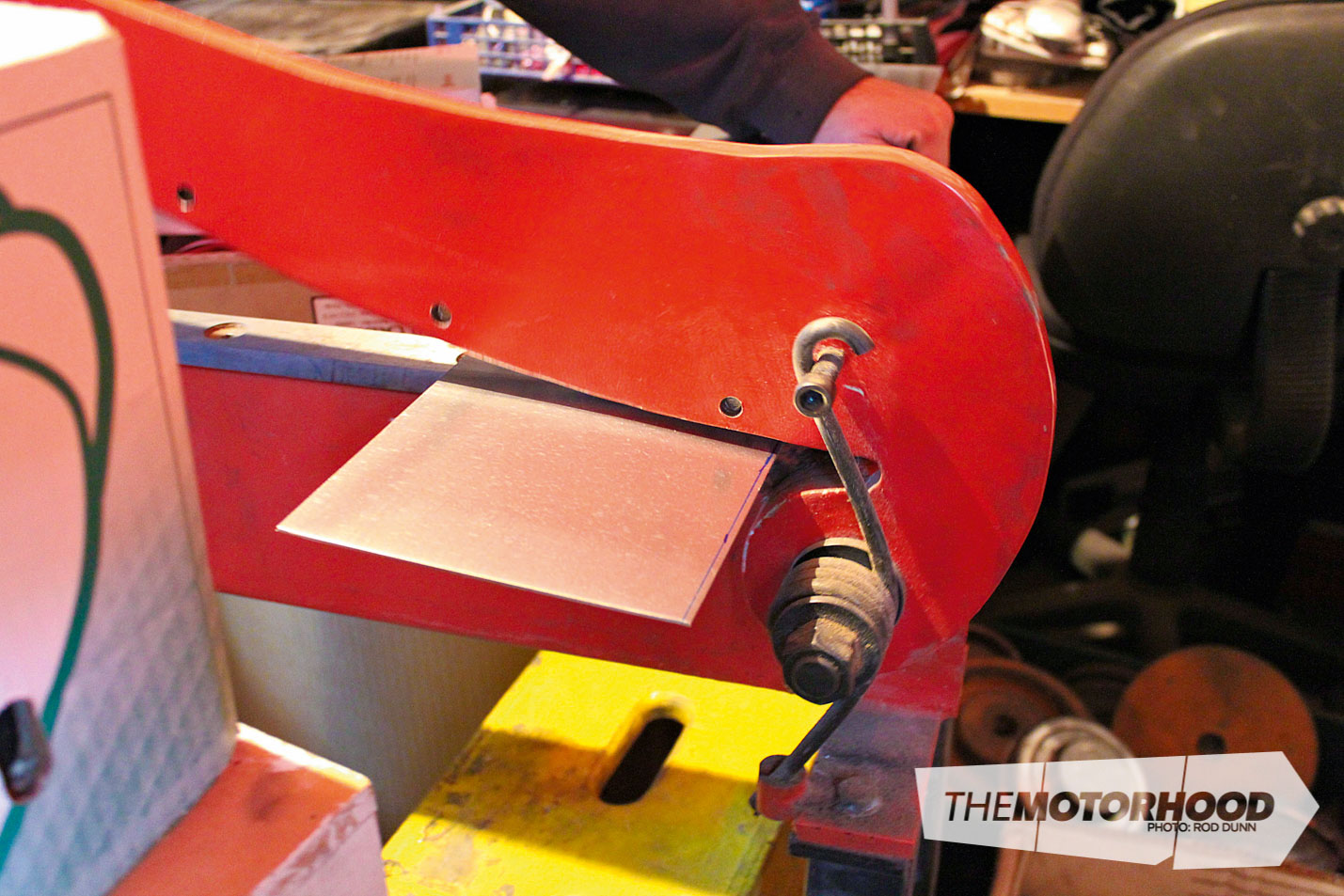

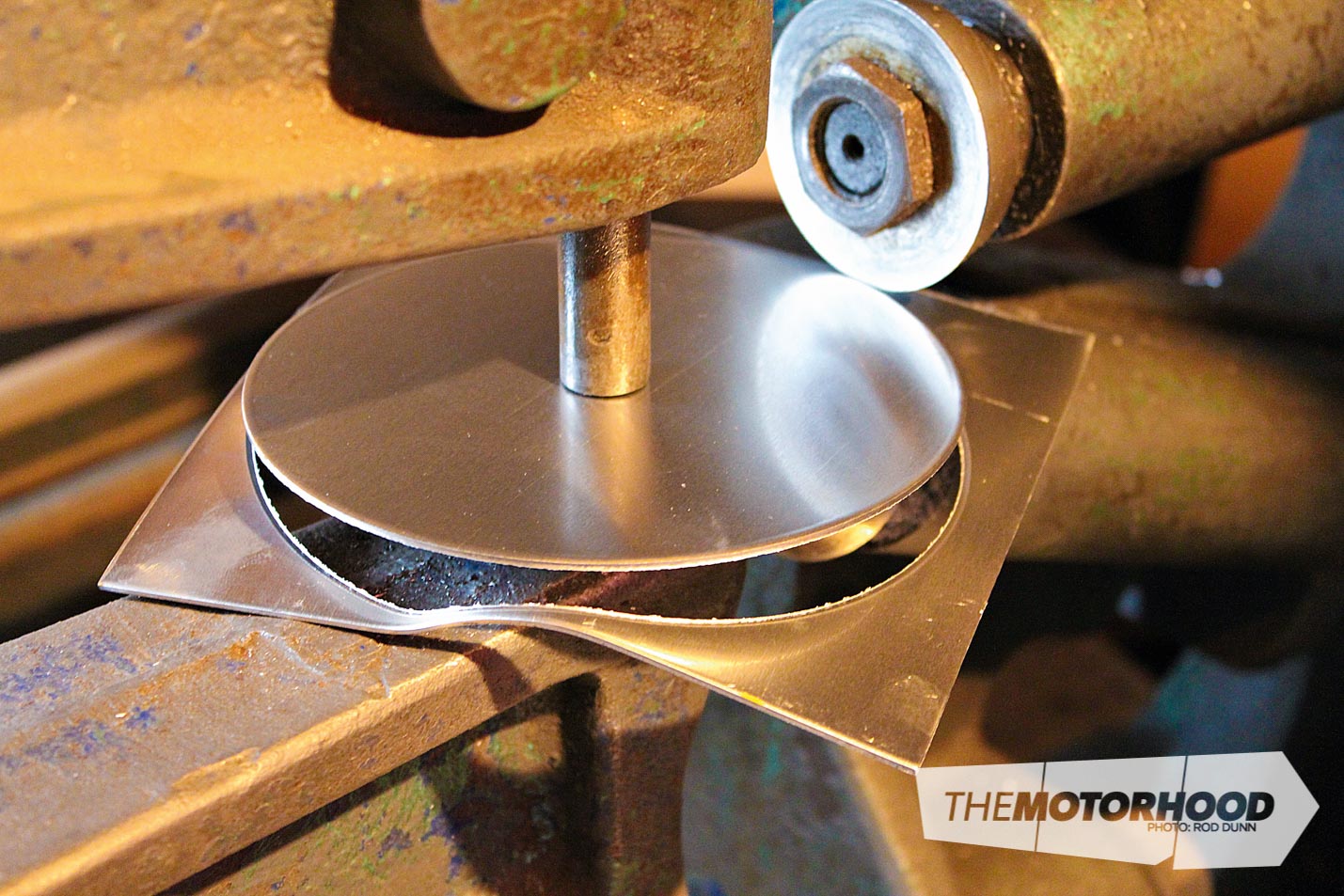

After selecting the material to use, it is cut to form a square. Virtually any ductile metal can be formed, from aluminium or stainless steel to high-strength, high-temperature alloys, copper, and brass. Phil uses mainly aluminium up to 3mm thick, and steel or copper up to 2mm.

The selected material is then clamped and spun in a machine, where a cutting wheel cuts a circle out of the metal.

We have the newly cut blank.

The new blank is clamped against the formed block by a matching-sized pressure pad, which is attached to the tailstock. A small amount of lube is applied to the surface of the blank. Phil uses grease. To centre the blank, a stick is jammed against the spinning metal, and the pressure backed off slightly on the pad, thus centring the blank in the lathe.

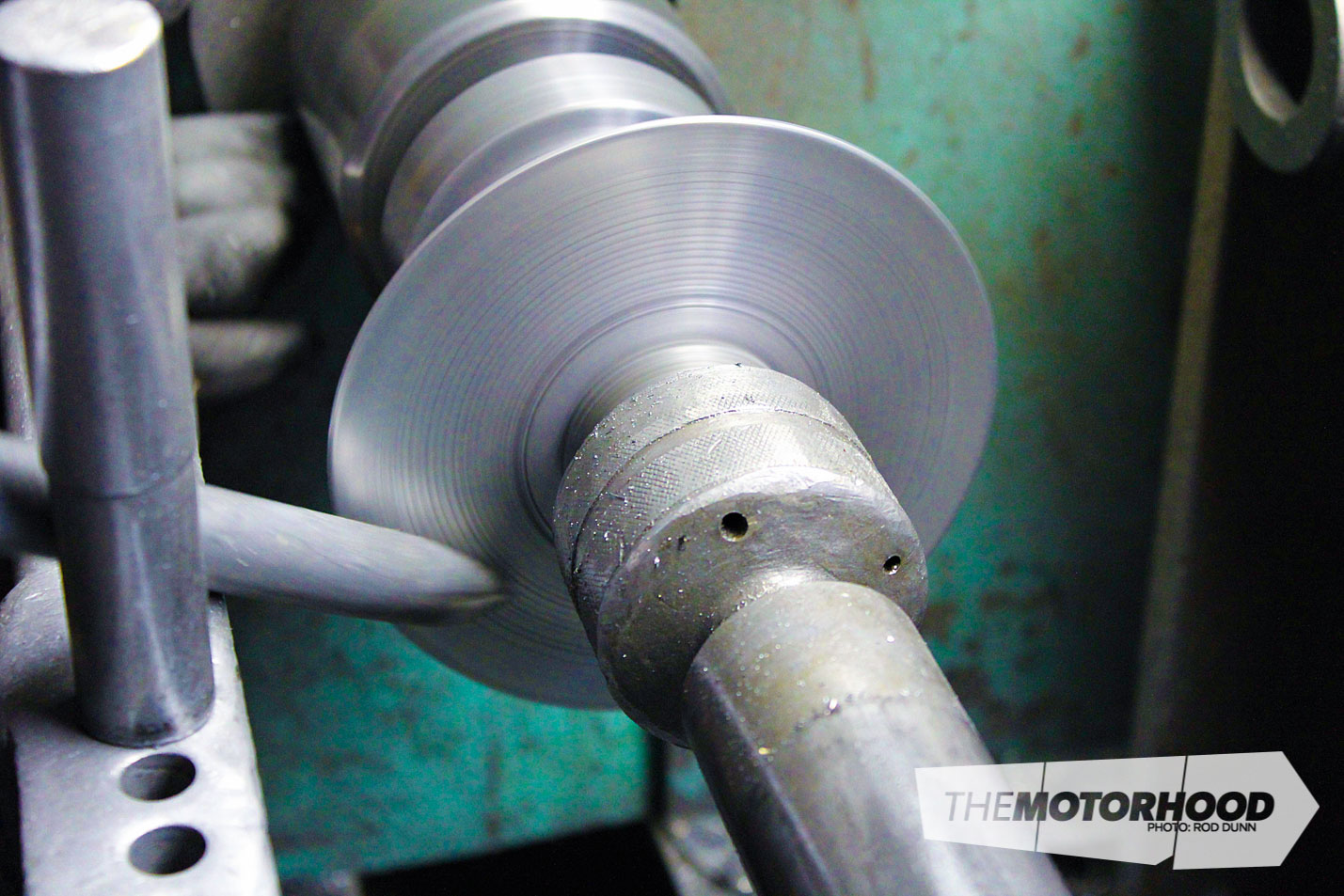

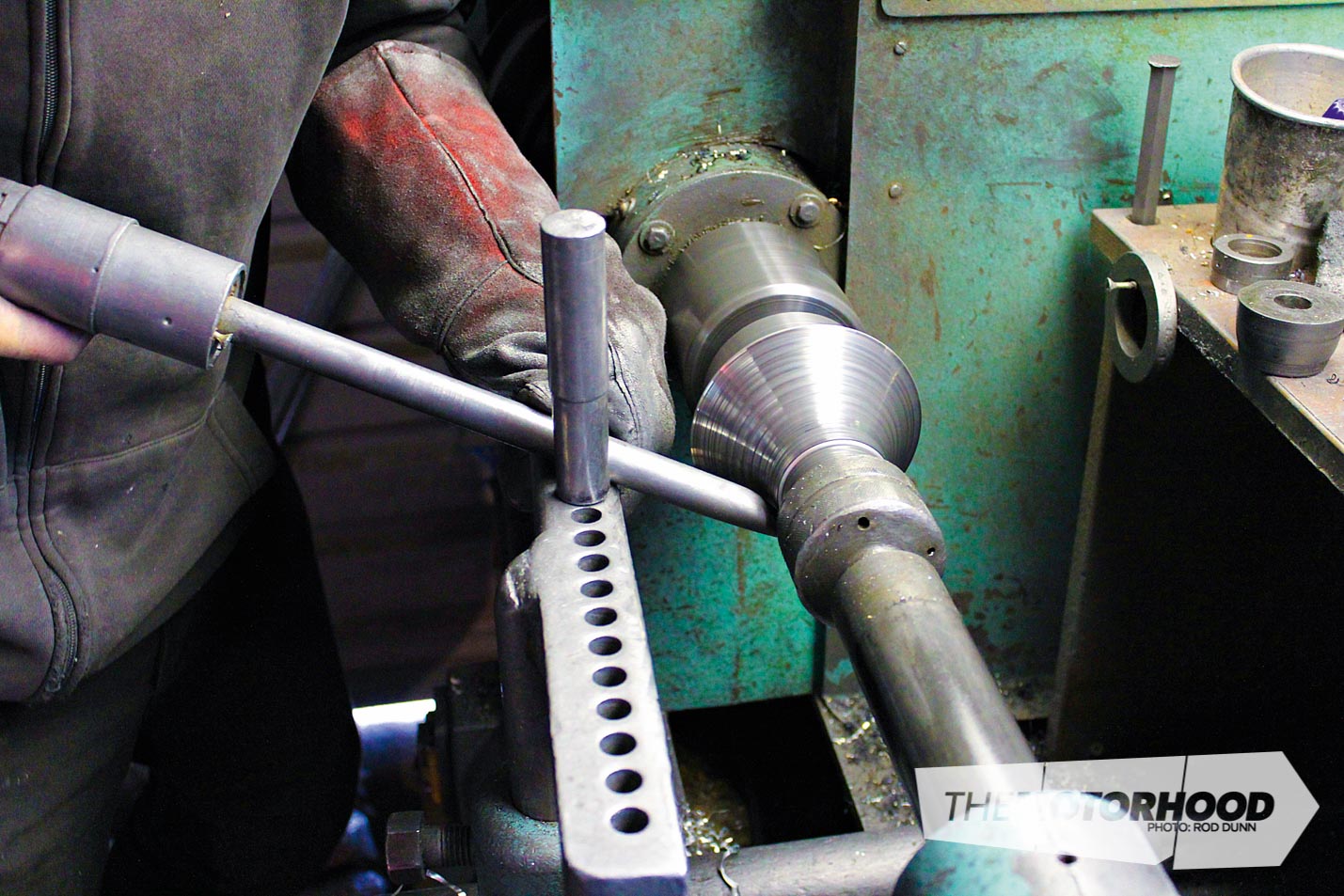

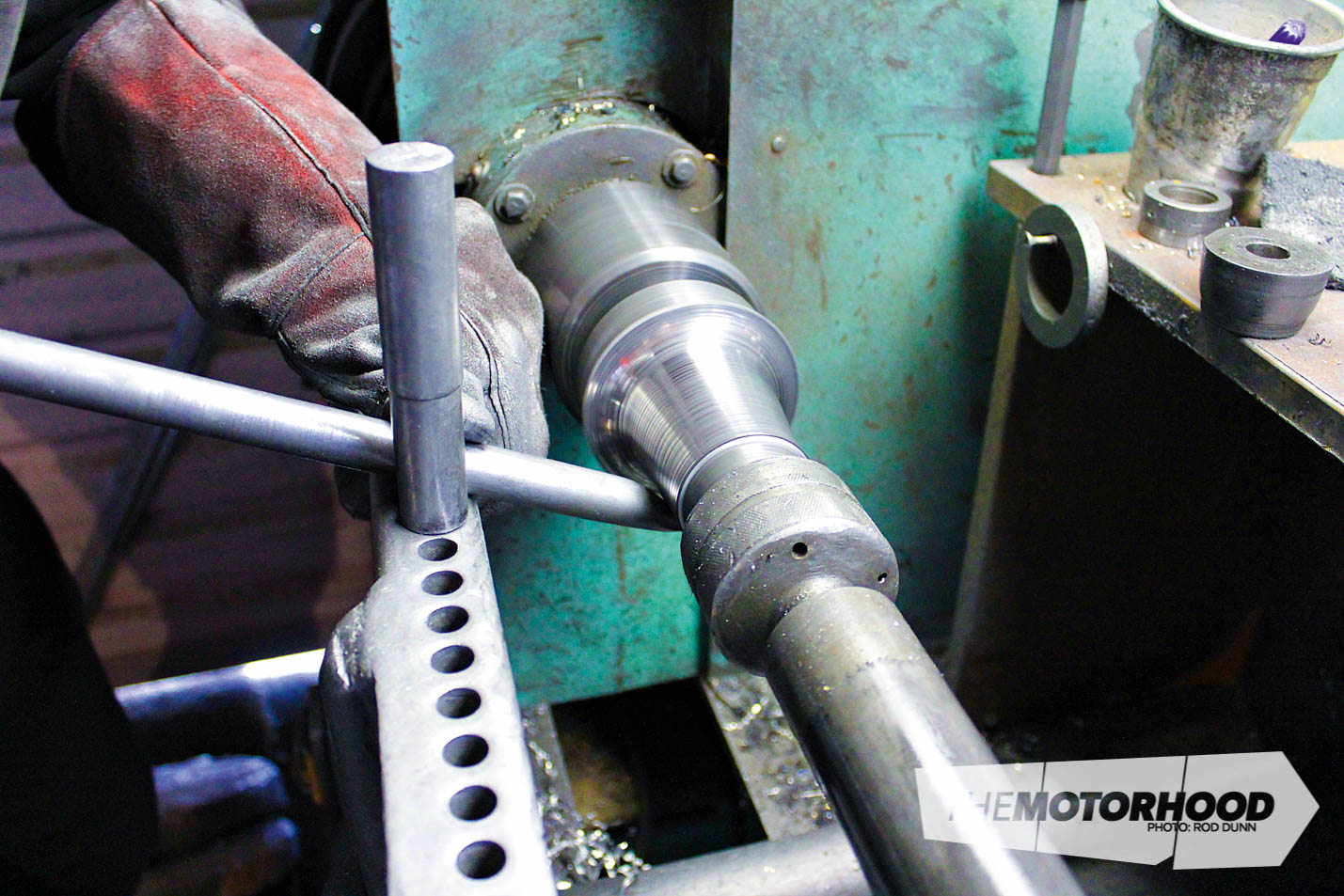

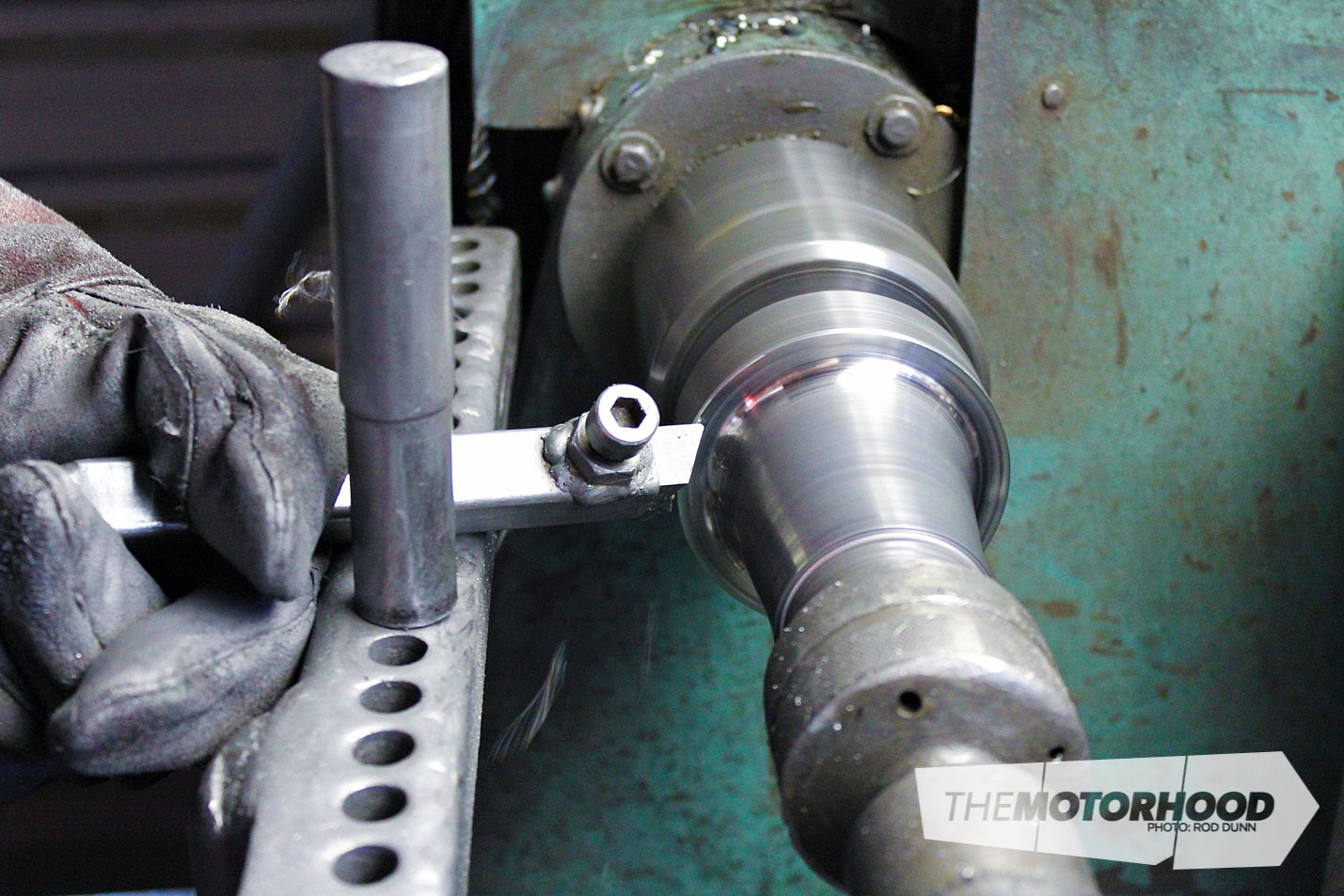

The process now begins. The hand tools are fairly basic. Phil uses a baseball bat handle with a steel shaft shaped to suit his own needs. All spinners have their own designs that suit their own requirements. Pressure is now applied to the blank, starting at the centre and working outwards.

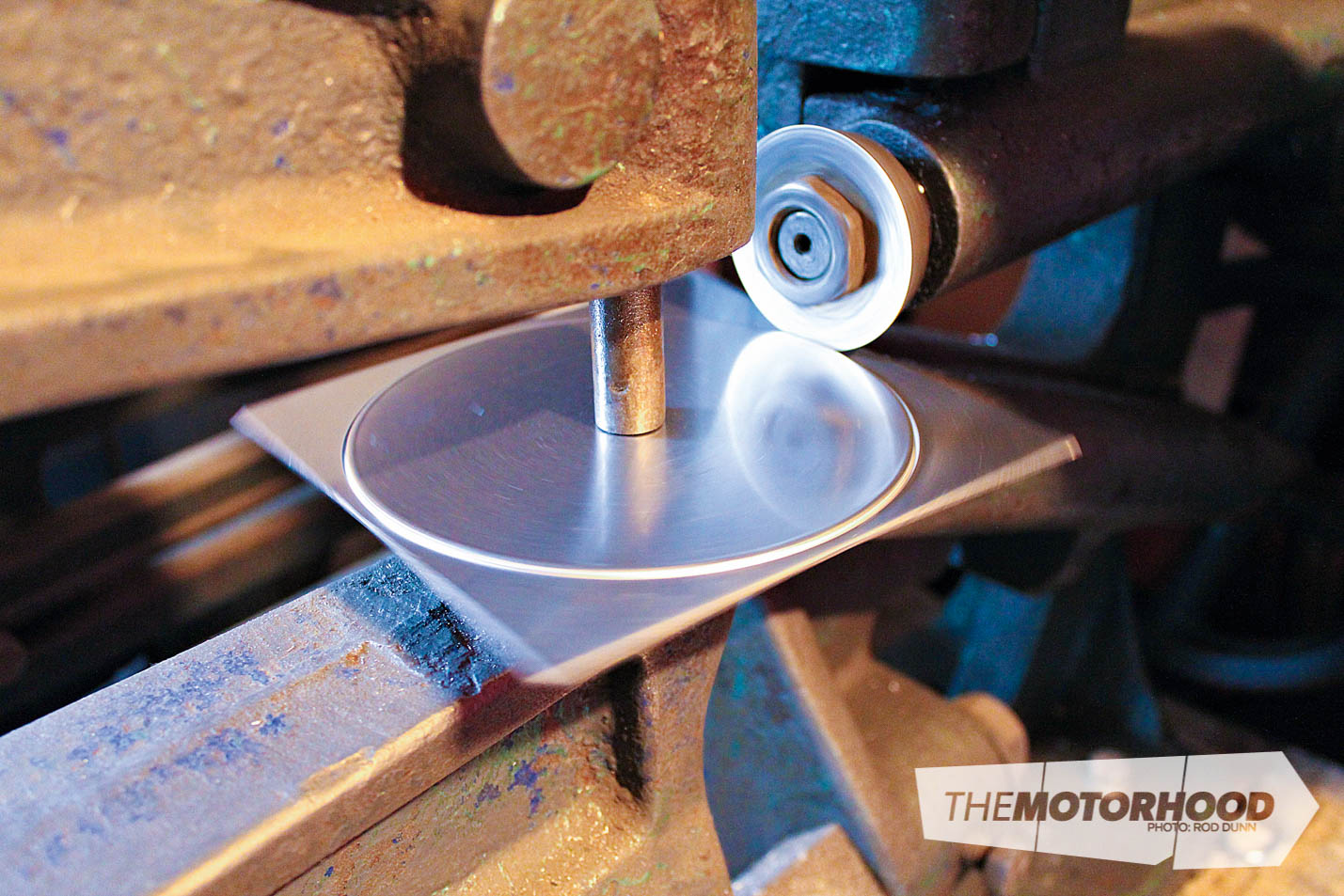

Still more pressure is applied, with the spinner careful to work the entire surface.

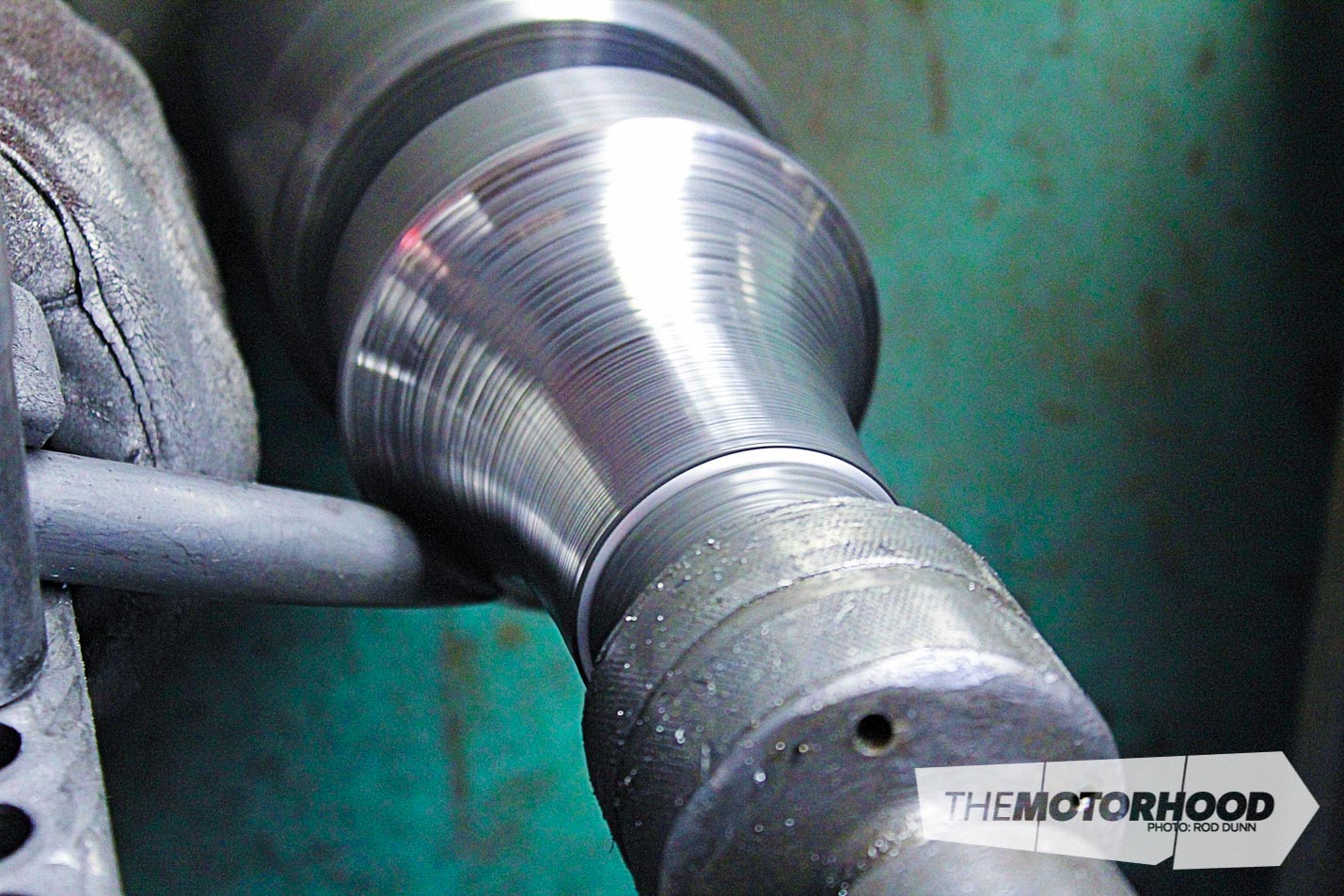

It is important to keep the curve in the metal, similar to working clay on a pottery wheel. If this isn’t done, it can collapse on itself.

And still, the metal is massaged.

Here is a close-up look at the surface of the metal as it’s being worked. Another reason for working the entire surface is to keep the whole piece of metal the same thickness throughout.

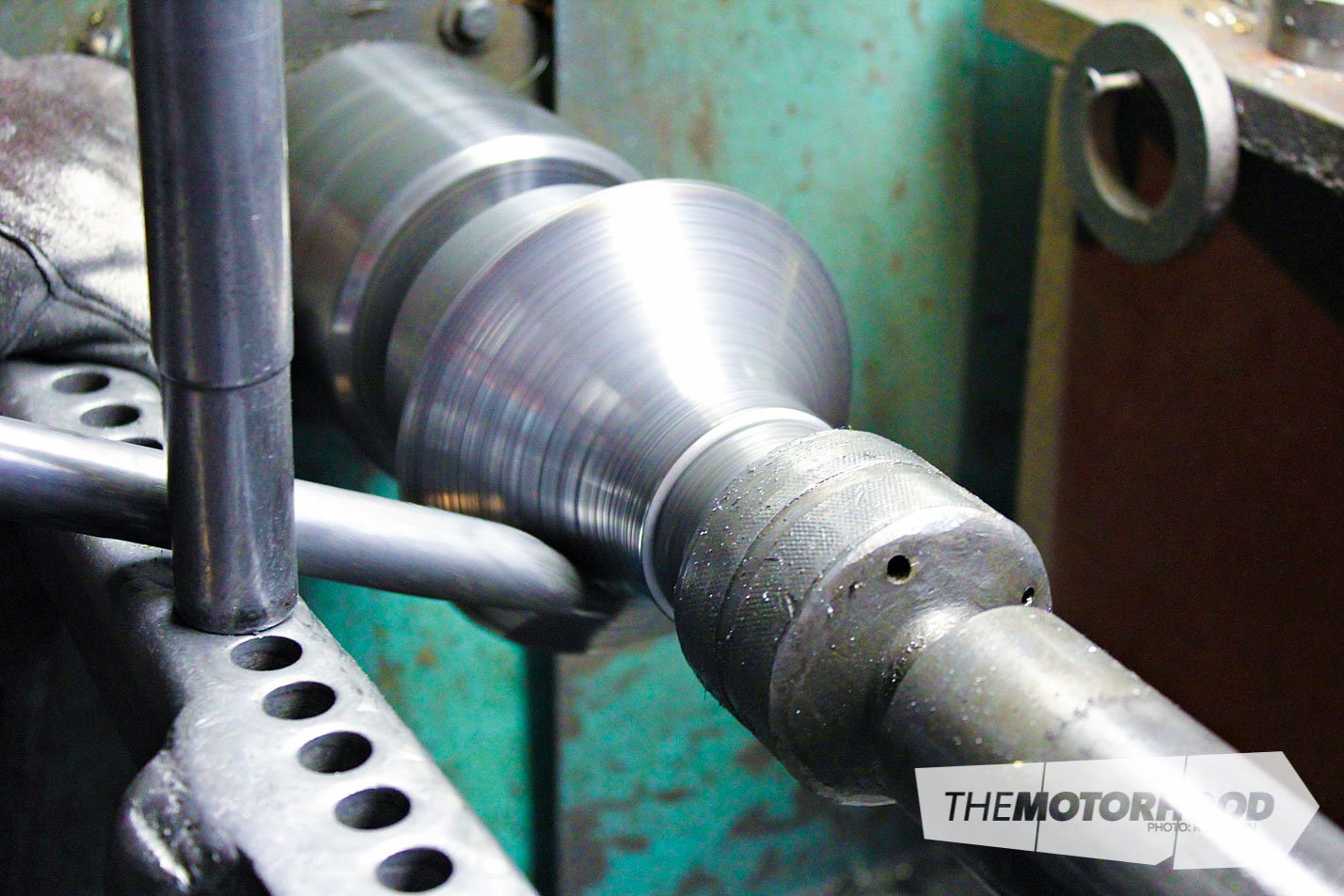

The metal has almost reached its finished shape.

You can see here how Phil is holding the tool to give him the best possible leverage against the metal.

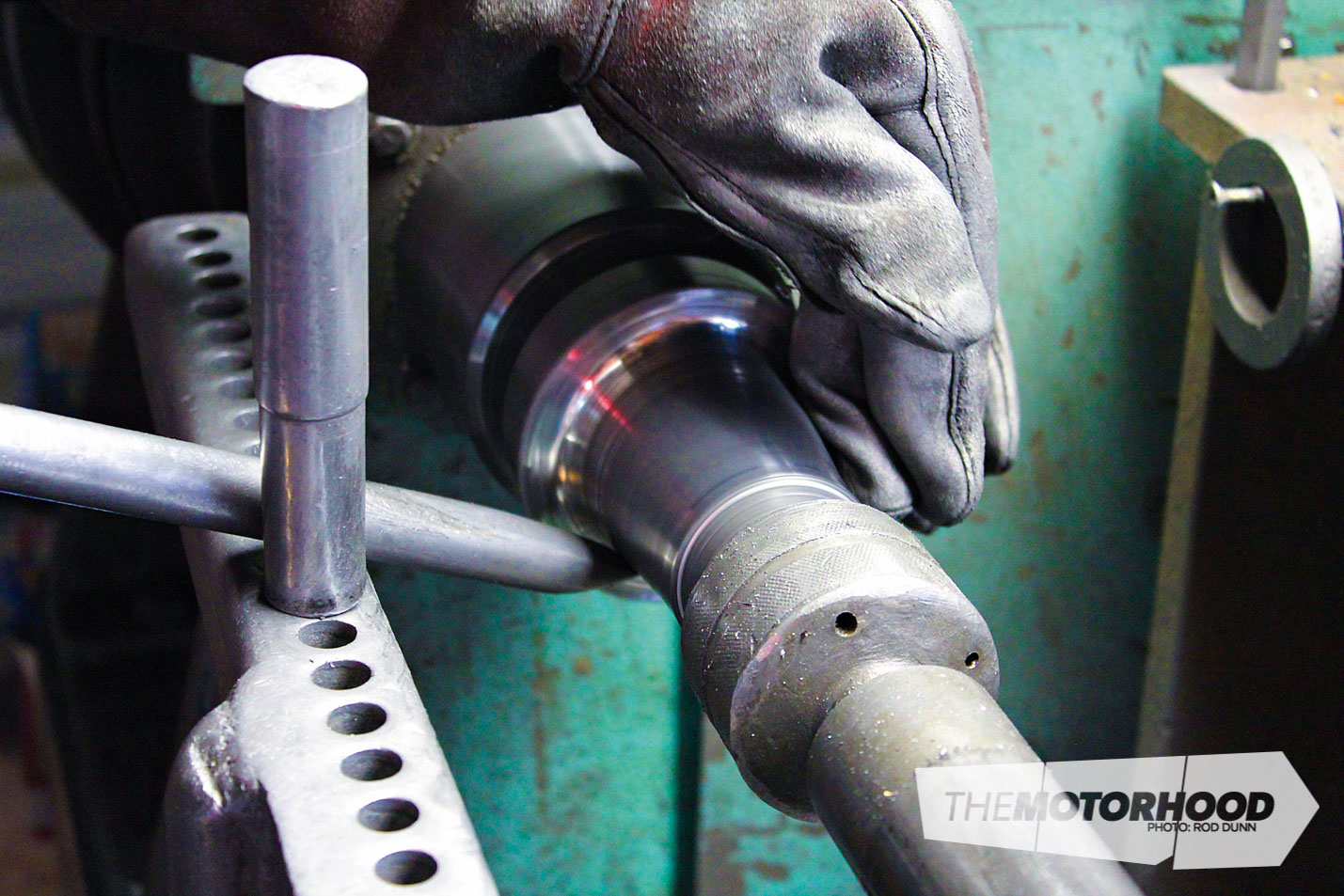

As the metal reaches its final shape, Phil runs his hand back and forth over the shape to gauge its thickness — a skill he has developed over his many years of spinning.

Lastly, the edge is given a trim to clean it up or to trim it to size. Phil sometimes uses a bit of wood for this, depending on the job and the material.

And here we have it, the finished product off the lathe — but there is still a little work left to be done before it makes its way to the customer.

Here, on the left, is the finished item: a ram tube. These can be made to just about any length.

As you can see from some of these formed blocks, the products that can be made are limited only by your imagination.

So there you have it: a bit of knowledge on the art of metal spinning. Next time you attend a show and see those awesome air cleaners or amazing hubcaps, you’ll be able to appreciate the work that’s gone into producing them.

Phil is often found at car shows around the country, so make sure to take a closer look next time you see him. You can also check out his work on his ‘Spun by Hutty’ Facebook page or give your local metal-spinning specialist a call to get something unique made yourself.

This article was originally published in NZV8 Issue No. 109. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: