data-animation-override>

“Ever wondered where and how your favourite brands began? Read on and you’ll soon find out there’s a whole lot more to them than you may realize! ”

Edelbrock

The Edelbrock moniker is one known to almost every person with an ounce of petrol in their veins. It doesn’t matter what age you are or what country you’re from, it’s almost a given — if you’re into cars, then you’ll know Edelbrock’s name. What is less known to most, though, is the story behind it. How did one man’s name end up plastered on just about every type of go-fast part the length and breadth of the globe?

It began in 1913 in rural Wichita, Kansas, when Vic Edelbrock was born. His father supported the family by running the local grocery store. After the store burned down in 1927, 14-year-old Edelbrock left school and joined the workforce in order to help support his family. He worked delivering Model T Fords from Wichita to farms scattered throughout the area. The rough, unpaved roads and the cars’ tendency to shake parts loose made him very capable with on-the-spot repairs. Given his growing skill with cars, he found work as a mechanic at a local auto repair shop, beginning his climb to the top of the automotive ladder.

The Great Depression of 1931 hit Kansas heavily, and he migrated to the relatively prosperous California, where he moved in with his brother, Carl. Working in downtown Los Angeles as an auto mechanic, he also met Katherine ‘Katie’ Collins, who became his wife just eight weeks after they met. The 22-year-old Edelbrock opened up his first auto repair shop in Beverly Hills with his new brother-in-law. Thriving business saw him move into his own shop in Los Angeles in 1934. This success continued, Edelbrock’s business grew further and he moved premises three more times between 1934 and the start of World War II.

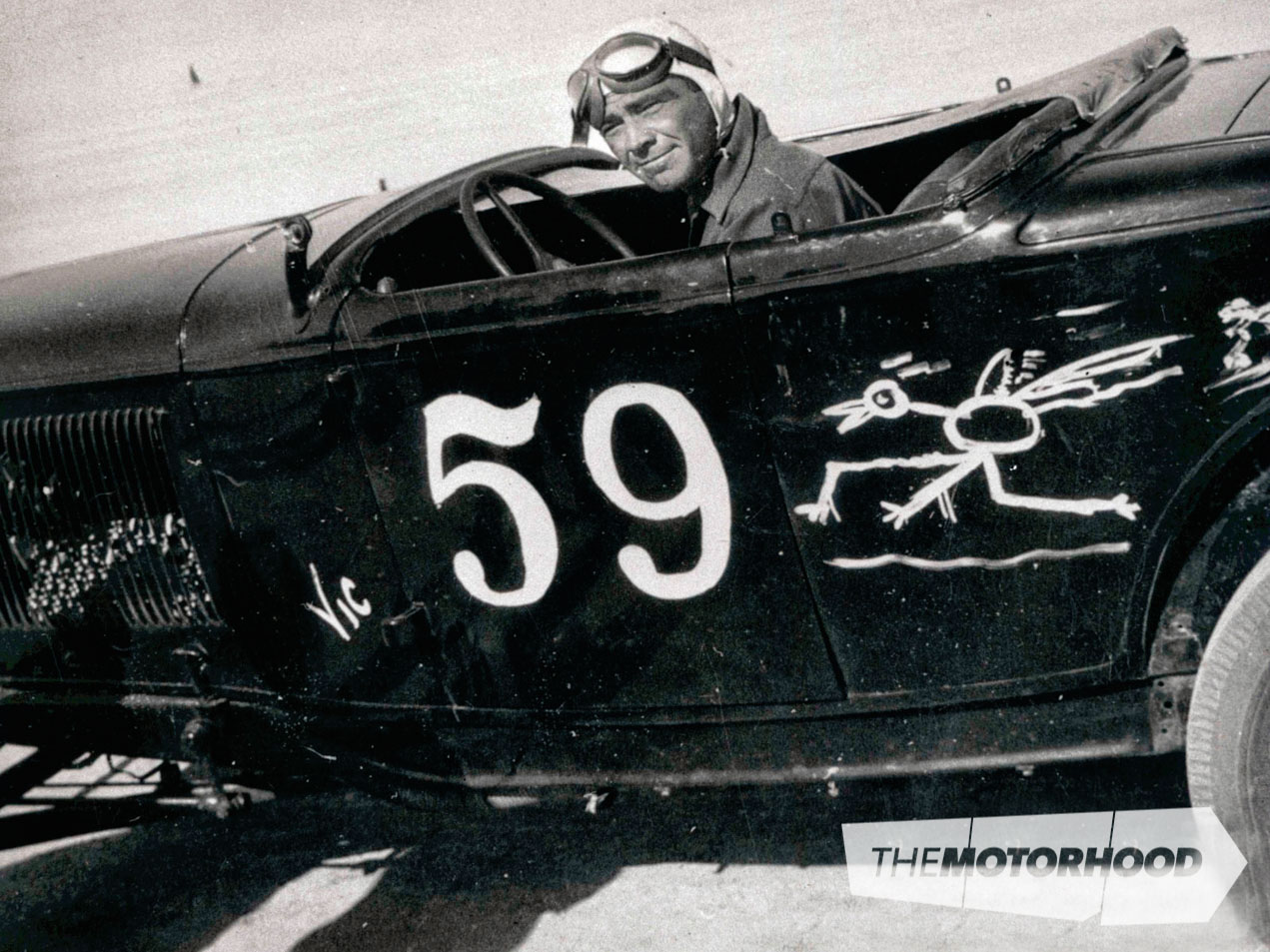

Vic and Katie’s only child — Vic Jr — was born in 1936, and he purchased his first project car in 1938. The 1932 Ford roadster provided him with his entry into the world of hot rodding and his desire to squeeze more power out of the Flathead V8 saw him design and build his first intake manifold, the Slingshot, which was the start of an innumerable list of performance parts bearing his name. Allowing the use of two Stromberg 97 carburettors, the Slingshot helped to push the ’32 to break records at Muroc and Harper dry lakes. The manifold’s development is also, interestingly, tied to the development of Phil Weiand’s High Weiand manifold. Edelbrock one day visited the foundry casting his Slingshot manifolds, saw the very similar pattern being worked on for Weiand, and promptly took to it with a hammer.

On December 8, 1941, the United States of America waded into World War II. As a married man with a child, Edelbrock was temporarily deferred from the military draft, but wanted to be a part of the fight for his country. Using his outstanding fabrications skills, he began to help in the construction of warships. With a ban on automobile racing, and shortages of consumables like gasoline and tyres, he had little choice but to shut down shop — the war required every last shred of metal, and he could not continue casting manifolds.

Vic and Katie were determined to get a good start after the War, and saved every penny they could.

In 1945 he found new premises, which would allow him to begin machining work using the skills he’d picked up from his work during the War. On the cards were designs for an intake manifold, as well as high-performance alloy heads for the flathead Ford V8. Edelbrock got busy, purchasing a lathe, a drill press, a milling machine, an enormous array of hand tools, and even a Clayton engine dyno. The dyno was instrumental in allowing him to prove that his designs yielded results.

With the Edelbrock brand rapidly becoming popular with racers, he was slowly inundated with mail, prompting him to release his first catalogue, Edelbrock Power and Speed Equipment. That gradually allowed the product range to extend, to eventually cover nearly every conceivable type of engine component.

In 1955, he began developing intake manifolds for the brand-new small-block Chevrolet engine, expanding his designs to cover Pontiac and Chrysler engines.

Unfortunately, tragedy struck Edelbrock in 1962, as Vic passed away due to cancer, at the age of 49. The reins of the company were handed over to his son, Vic Jr, who successfully carried the Edelbrock name well into the future, to the brand we know today, cementing the efforts of his father and turning him into a founding father of the automotive aftermarket industry.

Holley

Jump onto Trade Me and browse the listings for hotted-up classic and muscle cars. After a while, you might begin to notice a name popping up with alarming frequency. Why have so many of these cars had their factory carburettors replaced with Holley-branded items? Holley has grown to become one of the leading brands in fuel-delivery technology, and has been perfecting the art for over 100 years. As one of the easiest ways to extract power from an engine is to replace the factory carburettor with a better-flowing one, Holley’s reasonably-priced units have guaranteed it a place in performance history.

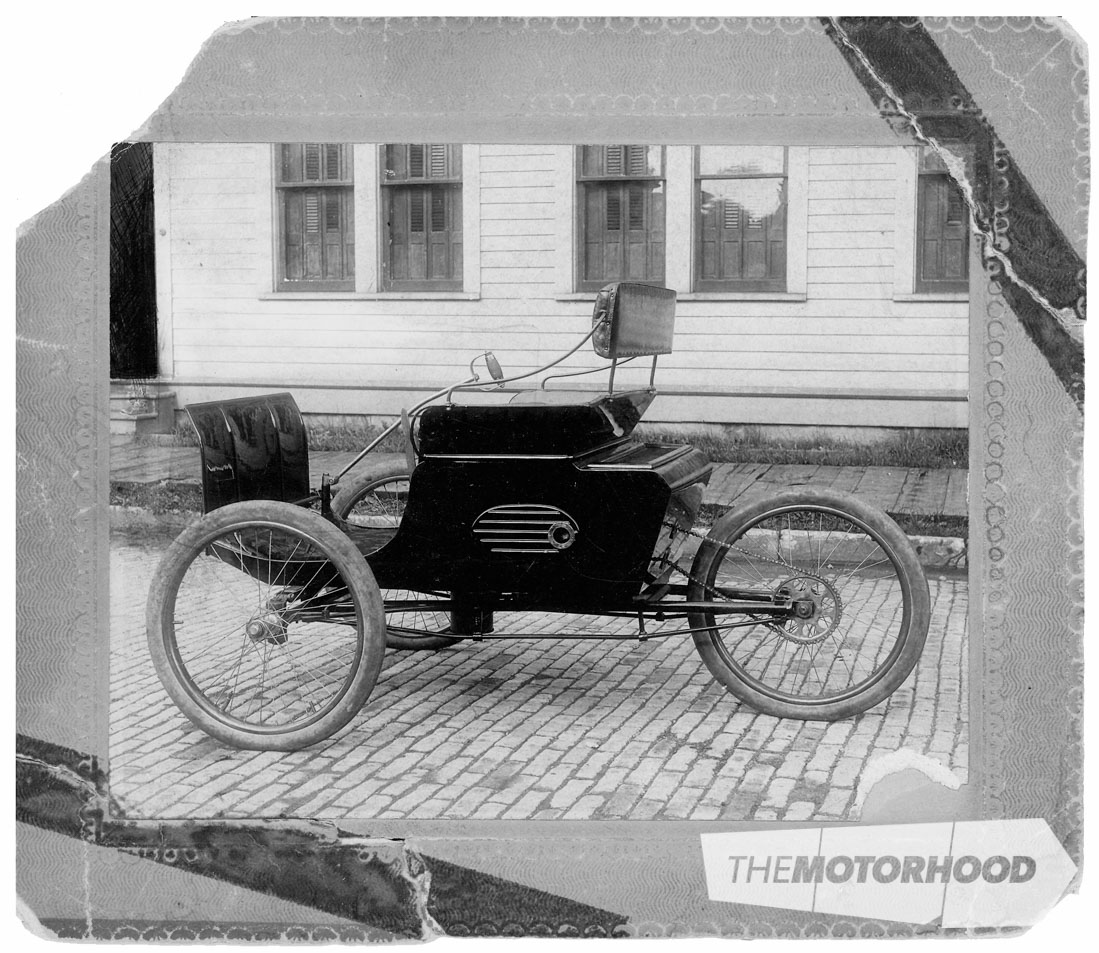

Brothers George and Earl Holley learned to make moulds for casting, and back in 1896 they started a company that built a one-cylinder three-wheeled vehicle. One thing led to the next, and the Holley Motor Company was born, with the introduction of the four-wheeled Holley Motorette in 1902. Their first carburettor was used in 1904 on the Curved Dash Oldsmobile, and Henry Ford commissioned them to produce a carb for the Ford Model T.

It wasn’t long before they were working full time at developing carburettors, eventually becoming a leading name in the industry.

Even World Wars I and II couldn’t stop the company, as its products featured on automobiles, planes and boats used in the war effort. Over half of the carburettors supplied during World War II were Holley-branded products!

Public demand for cars surged after that, automotive manufacturers’ production went through the roof, and Holley was right in the thick of it. Business was well and truly booming, and Holley expanded its production to include repair parts for service stations and garages.

The Holley-branded four-barrel carburettor as we know it was born in the 1950s, and its 4150 four-barrel carb featured on the 1957 Ford Thunderbird. Its enormous performance characteristics did not go unnoticed, and soon Holley’s four-barrel would be just about standard fare on the era’s toughest street machines. Development of the design led to the introduction of the high-performance Double-Pumper and Dominator series carburettors in the 1960s, designs which are still held in the highest regard to this day.

The Holley ‘Blue’ electric fuel pump was introduced in the 1970s, and became one of the most popular aftermarket fuel pumps in automotive history, still going strong to this day. Sure it’s a little antiquated and makes a bit of noise, but it’s versatile, reliable as hell and excellent value for money — check how many tough street and drag cars we’ve featured that use the Holley Blue in their fuel system!

Following the 1970s oil crisis, which facilitated demand for more economical cars, as well as rapidly advancing technology, Holley began looking into electronic fuel injection (EFI). Keeping up with technological trends has seen it effortlessly ride the performance aftermarket wave, acquiring several other top brands whilst at it. Holley now also owns NOS (Nitrous Oxide Systems), Weiand, Flowtech Exhaust, and Hooker Headers, to name but a few.

It was the Holley brothers’ ceaseless dedication to research and development of technology that lead the brand to become one of the largest names in the motoring world. Yes, it did take a century, but starting from a rudimentary one-cylinder engine and winding up as a world leader in fuel-system technology with an endless list of go-fast bits revered by the world’s petrolheads — how’s that for progress?

Weiand

Like so many of his contemporaries, the story of Phil Weiand’s world-beating brand began in Los Angeles, honed by his desire to go faster on salt flats and dry lakes. Phil Weiand was born in Los Angeles in 1913 and, at the age of 14, acquired his first car — a 1922 Ford Model T tourer, traded for a mandolin. With a keen eye for a deal, Phil managed to replace the touring body with that of a Model T bucket, and with the seeds of hot rodding sown, he fabricated his own exhaust and intake manifolds using skills he’d picked up in high school shop-class. Upon graduation, Phil suddenly had more time and money to devote to his quest for speed. Through clever hustling, he was able to fully kit the little Ford four-cylinder out, sourcing a Rajo OHV conversion, Laurel camshaft, Stutz dual ignition (for automotive, rather than aeromotive, application), aftermarket pistons, and a single downdraft carburettor which he perched on the intake manifold of his own design. With his rod ready, Phil hit the Muroc dry lake in 1933, achieving a satisfactory 91.8mph. A need to go faster saw him make further changes to the car, eventually pushing it on to 116mph by the end of the 1933 season. But the 1934 season didn’t hold as much success for Phil. At a high-speed trial run on Lennox Boulevard (now LAX), Phil took a passenger with him — at 110mph, the terrified passenger pulled the handbrake, sending the car into a skid which threw Phil from it. His back was broken, and he spent the rest of his life confined to a wheelchair.

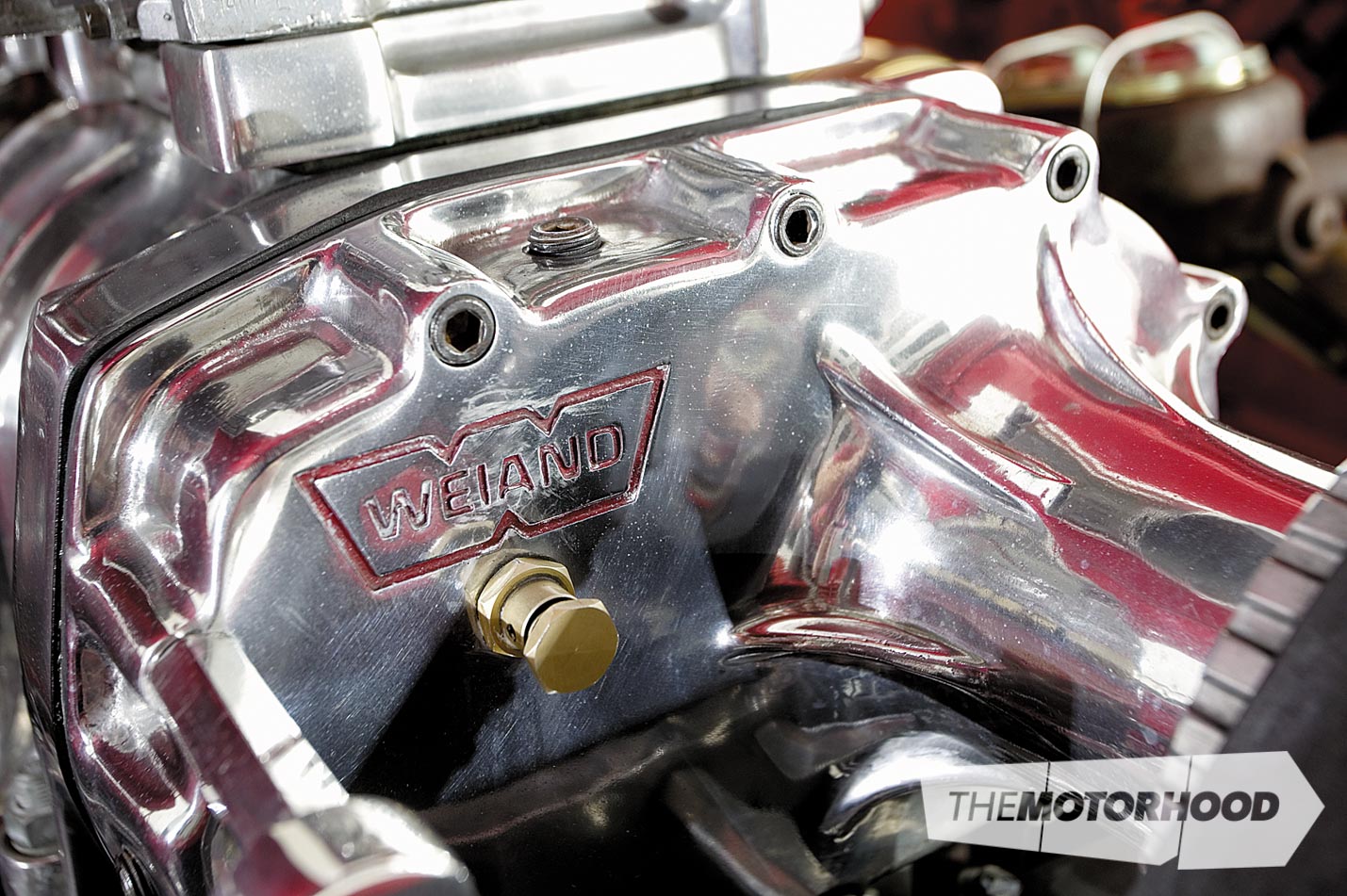

The sudden loss of mobility was a huge shock to a man who lived for speed, but after a few years Phil purchased a ’29 Ford coupe and converted it to hand controls. Now mobile again, he eventually tired of the four-cylinder’s limited performance and, in 1938, went for a ’34 Ford coupe equipped with the hugely popular flathead V8. Wanting to extract more power from it, Weiand began looking at aftermarket intake systems, noting where improvements could be made on Jack Henry’s twin-carburettor manifold. Borrowing US$250 (a considerable sum) from his mother, Phil went to a pattern-maker asking him to make him a manifold pattern. That pattern-maker had also been contracted by Vic Edelbrock to make a pattern for his Slingshot manifold, and Weiand’s finished manifold ended up looking very similar. Not happy with what he saw upon visiting the pattern-maker, Vic Edelbrock took a hammer to Weiand’s manifold. Undeterred, Weiand purchased his first drill press and began manufacturing his initial batch of High Weiand manifolds, the first of which was installed in his ’34 coupe.

To spread word of his manifold, Phil employed a very clever marketing strategy — he’d find the losers of late-night Los Angeles street races, and ask them if they wanted to go faster, promising that his manifold would help them do so. The popularity of the manifold rose as a result, and Weiand began manufacturing and distributing an increased production run.

Though World War II put a dent in his manufacturing, he kept himself busy by collecting aluminium. Mainly pots and pans, it didn’t matter, if it could be melted down and used for casting manifolds after the war, he’d collect it. The boom in business after the war saw Weiand produce more intakes, and also apply his knowledge to build new intake manifolds and cylinder heads. This carried on with his production of cylinder heads and intake manifolds for the newer-design OHV engines coming out in the late ’40s and early ’50s.

Not one to let an opportunity glide by, Weiand noticed the ever-increasing popularity of the GMC blower and began designing and manufacturing an intake manifold to suit. Not long after his supercharger manifolds were released, and delivered results on several successful racing cars (including the twin-engined Bustle Bomb dragster, which broke 150mph), Weiand began developing his own line of superchargers based on the fundamental design of the GMC blower. Weiand’s business was thriving and, to guarantee consistent quality and supply of his products, he began looking at setting up his own aluminium foundry. In 1958 he started the All-Aluminium Foundry in Los Angeles, guaranteeing him control over every aspect of his production. Not only that, but Weiand was the only automotive aftermarket manufacturer to own a foundry, meaning that he ended up undertaking casting work for some of his competitors as well!

In 1963, the Speed (now Specialty) Equipment Manufacturers Association (SEMA) was founded by a range of industry leaders, including Weiand, who was made a member of the board of directors. His contribution to the world of performance was recognized in 1975, when he was inducted into the SEMA Hall of Fame.

Phil passed away not long afterwards, in 1978, aged 65, handing the company’s reins over to his wife, Joan. She must have known what she was doing, as Weiand still managed to succeed in an ever-competitive automotive aftermarket, and she continued as head of the company for 20 years before selling it to Holley Corporation. Joan Weiand was inducted into the SEMA Hall of Fame in 1995, making the Weiand duo the first husband-and-wife team to make the cut. Looking back at everything they achieved and the influence they had over hot rodding as we know it, it’s the least hat they deserve.

Moon

It might not have been Dean Moon’s intention, but the pair of eyes forming the logo of his Moon speed brand just so happens to have become the unofficial logo of the entire hot-rodding scene. The ‘Mooneyes’ have become an almost ubiquitous sight in the global car scene, eclipsing the man and the story behind their legendary status.

Dean Moon, as his legacy no doubt makes clear, was heavily into cars and speed, and possessed a huge amount of technical know-how. He first made a Moon fuel block in high school, and later went on to design and sell them to hot rodders as part of a large range of speed equipment. During the Korean War, over the beginning of the 1950s, Dean served with the US Air Force. After returning from the war he used his technical savvy to set up shop behind his parent’s restaurant in Santa Fe Springs, Los Angeles, producing aftermarket speed equipment. This equipment would become a staple feature amongst hot rodders and drag racers worldwide.

In the 1950s, a racer named Creighton Hunter built and raced a 1924 Model T Roadster at the Santa Ana drag strip. It was on this Roadster that the first example of Moon’s logo would appear — the car bore the number ‘00’, but a dab of paint saw pupils added to transform the numbers into what would soon become a world-famous logo. Dean ran with it for his products, but had it professionally redrawn in 1957 by a friend who worked for Disney, and the revised version remains in use on Moon products to this day.

Of Moon’s vast array of go-fast creations, the most recognizable is almost without a doubt the ‘moon disc’, a smooth, aluminium wheel cover that became a staple feature within the Californian hot-rodding scene, and later worldwide. It wasn’t just the moon discs that captured the hearts of hot rodders, though — Moon’s foot-shaped gas pedals and small-capacity fuel tanks also were immensely popular with rodders for their functional form. Recognizing the difficulty racers of the era had with sourcing reliable small-capacity fuel tanks, Moon designed and made his own aluminium tanks. Coming in a range of sizes, Moon’s tanks could be made to fit just about anything, and they became an integral part of the ’50s drag scene. Such was the popularity of his wheel covers and fuel tanks that, even now, any product bearing a resemblance them are known colloquially as ‘moon discs’ and ‘moon tanks’.

Moon didn’t just build parts, though. He also applied his knowledge and skill to help construct extremely fast cars. In 1961 he built the Mooneyes dragster which ran 147mph at 10.29s on its first run. Built more for promotional purposes than actual competition, it went on to run a sub 10-second pass with the addition of a top-mounted supercharger.

Dean didn’t limit his focus to the drag strip, and also had the iconic streamlined Moonliner built by Jocko Johnson which, when driven by Gary Gabelich, hit 285mph (459kph) on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah.

Dean Moon lived to go fast, but unfortunately died only aged 60, in 1987, of ongoing health complications. Though his death was a huge blow to the Moon brand and the hot rodding world, his legacy still lives on. Thanks to Dean’s friend — and Moon’s Japanese distributor — Shige Suganuma, Mooneyes USA was founded to keep the legend that Dean Moon built alive. Shige bought and renovated Dean’s original Moon Equipment speed shop at 10820 Norwalk Boulevard, Santa Fe Springs, California. With Shige’s dedication, that famous pair of eyes lives to see another generation, rather than becoming a nostalgic relic from hot rodding’s golden age.

Cragar

The timeless Cragar S/S wheel design is a staple feature of hot rodding, but less well known is the brand’s turbulent history, which is nearly completely unrelated to the wheels it is now best known for, as the company actually started out producing popular go-fast induction parts; chiefly cylinder heads.

Near the end of the ’20s, Harry Miller and George Schofield teamed up with the aim to produce performance parts for the new Ford Model A engine. In 1929, Miller-Schofield designer Leo Goosen designed a revolutionary aftermarket cylinder head, dubbed the Valve-in-Head. The head featured eight overhead valves actuated by the factory camshaft and pushrods, but Goosen’s design savvy saw him design the head’s intake and exhaust ports to match the factory Ford in-block ports, meaning the OEM intake and exhaust manifolds could be re-used. With a 6.75:1 compression ratio and a reasonable price, this was a hit with Californian racers.

Harry Miller left Miller-Schofield in 1930 to form another racing parts company, and the result of this was Miller-Schofield’s bankruptcy. Schofield continued producing the valve-in-head cylinder heads, in collaboration with a local high school shop teacher, but that venture also failed. Later that year, former racer Harlan Fengler teamed up with the prosperous Crane Publishing heir, Crane Gartz, to form Cragar Corporation (formed by joining the first three letters of Crane Gartz’s first and last names). Cragar purchased the tools, machinery and castings for the Goosen-designed heads, and began manufacturing the Cragar Valve-in-Head. Production efficiency saw Cragar able to sell the already popular design for even cheaper than Miller-Schofield had and, with its unparalleled bang-for-buck, the Cragar Valve-in-Head sold incredibly well. Unfortunately the company folded in 1932, bowing to the economic pressure brought about by The Great Depression. Now this could have been the end of Cragar Corporation — confined to a dusty tomb in the depths of hot-rodding history — but that was not the case thanks to an ex racer named George Wight. He owned a quarter-acre salvage yard in Bell, California, knew quality speed equipment inside out, and had amassed an enormous collection of used speed equipment. Many local young hot rodders, one of whom was a very talented racer and aluminium worker named Roy Richter, saw Wight as a go-fast guru. In constant demand for advice and parts, he turned his yard into a speed shop in the late ’20s, naming it Bell Auto, and it became the de facto meeting spot for local racers. Wight organized a series of race events at Muroc, in conjunction with Gilmore Oil, elevating his status in the Southern California hot-rod scene.

When Cragar failed, Wight contacted Crane Gartz and found out that all the company’s patterns, fixtures, and surplus stock was on the market — the sale was completed in 1933. Determined not to fail where the Head-in-Valve design’s previous manufacturers had, Wight kitted his machine shop out with Cragar tooling and manufacturing equipment. Employing a local foundry to cast the base cylinder heads, and several ex-Cragar employees for machining, Wight was soon producing enough Cragar Valve-in-Heads that the price could fall below $100, unbelievably cheap at the time. he then went on to develop a dedicated racing version of the head, named the Improved Cragar, which featured larger ports and a compression ratio of 7.5:1. These also sold extremely well, and Leo Goosen’s head design was finally recognized widely as a success. George Wight unfortunately died during World War II, passing the Bell Auto business on to his widow.

During World War II, the aforementioned Roy Richter put his considerable fabrication ability to work in the aviation industry and, following the conclusion of the War, he sold his hot rod and put all his money towards leasing Bell Auto and its inventory.

The post-war boom in hot rodding saw Bell Auto continue to thrive, and the Cragar brand maintained favour with both older and younger generations of hot rodders. So how, then, did Cragar go from cylinder heads to wheels? The custom wheel market of the era was traditionally limited to deep-dish chrome wheels, essentially chromed factory steel wheels with the centre section reversed (providing lower wheel offsets for a tougher appearance). Richter began working on a design for an attractive, affordable, and high-quality wheel of his own, in response to several wheel manufacturers’ offerings being nothing more than an alloy centre section riveted to a steel rim.

The Cragar S/S was a two-year work in progress, and a revolution in design and quality upon its release to the public. Richter pioneered a pressure casting process to bond the alloy centre to the steel rim — no rivets were used, but the finished result was far superior in strength compared to its contemporaries. Demand, and soon production, of the Cragar S/S skyrocketed and Richter needed to open three new production facilities to meet demand. The little Bell Auto business had well and truly made it.

As a true pioneer within the automotive industry, Roy served as the president of SEMA from 1969 to 1971, and was inducted into the SEMA Hall of Fame in 1974. He died in 1983, aged 69, but the Cragar brand continues to operate and produce wheels to this day. Roy Richter’s Cragar S/S is arguably the best known and most successful custom wheel ever, but that shouldn’t overshadow the rich history of the brand which secured its success, not through huge corporate investment, but as recognition of the hard work put in by a few regular guys.

This article was originally published in NZV8 Issue No. 114. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: