data-animation-override>

“So you want a car that does everything, but think it’s well outside your budget? Think again, as Pete Withers’ VK Commodore has proven that anything is possible”

Let’s face it, we all want everything, and we all want it for nothing — be it the perfect woman, with the perfect personality, and all the curves in the right places, but with none of the strings that come attached, or the job that takes just an hour a week to do from the comfort of your couch, yet pays you 10 times your current wage. Sadly, reality dictates that these things are like unicorns, and that women who rate a perfect 10 on all aspects are few and far between — although, apparently they do exist …

Auckland refrigeration engineer, Peter Withers, has nailed himself one of these mythical creatures; no, I’m not talking about the perfect all-round woman — although he says he’s got that too, but we haven’t met her yet — but the perfect all-round car.

After stepping back from competitive motorsport a while back, five years ago Peter found himself wanting to get back behind the wheel again. This time, though, it had to be just for fun, not an all-out drive to win. Certainly, Peter had no desire to go pouring money into a black hole. After much deliberation, he decided that whatever car he purchased needed to be street legal in order for him to be able to drive to and from the track, just like it was in the good old days when real men drove to the track, raced, then drove home again. This meant that the vehicle must also be big enough to carry all the tools and racetrack essentials, but not so big that Peter couldn’t throw it around the track with ease.

The more he thought on it, the more Peter knew what he was looking for, and that was an ’80s Commodore. Due to the use of Commodores as touring cars back in their heyday, plenty of spare parts and aftermarket components are available, and the old 308s under the bonnet are pretty easy to work on. With this mindset, Peter headed over to Trade Me. After looking at many cars, Peter began to wonder if his Commodore dream was a fruitless one.

“I looked at many cars, but soon realized the difficulties in finding a suitably priced road-legal race car or a viable road car that could be converted into a race car,” he says of the search.

Then, Peter found just the thing. While many cars lost their tags when they were transformed from road to circuit, the car he found had been put on hold for the duration of its racing career, and was returned to street legal when its life of serious competition had come to an end. This 1986 VK came up in Christchurch, and Peter flew down to look at it. A hoon around the block later, and he was sold. So, too, was the car.

“I knew that there were lots of things that I needed to do to get it up to scratch, but, for me, one of its most attractive features was the fact that it had all the paperwork to accompany its LVV certification, as well as a motorsport logbook dating back more than a decade,” Peter explains of the purchase.

The car’s interesting history goes back to well before its life as a race car, with it having been used as a taxi in its early years — and no doubt plenty of hoons ended up in the back seat rather than the front.

Having not owned a V8 before, Peter found Google a useful source of information, as he downloaded and printed out screeds of details about 327ci small block Chevs — the engine that was fitted to the car — Holley carburettors, and anything else that seemed of relevance at the time. To add to Peter’s knowledge base, he also started collecting and reading books on suspension, race car set-up, and engine building, surprising himself with this new world of information.

“I became fluent in a new language. Roller rockers, alloy heads, and stroker kits became everyday topics of conversation in our house!” he laughs.

Why bother learning all this since he’d started with a complete car, you may ask? Well, the car had to do everything Peter wanted of it on a limited budget, and the biggest place he could save cash was in repairs and maintenance. Peter’s knowledge soon came in handy, as the first few outings on the track saw the car end up with engine overheating issues and warped brakes. With these, it soon became apparent that the manually shifted TH400 transmission the car came with was not going to be a long-term solution.

“Mr Google again came into play on a daily basis, helping me sort out radiator, brake components, and gearbox set-up information. By now, the printer needed a new toner cartridge, and I needed another lever arch file,” Peter recalls.

During his Trade Me searching, Peter came across most of the parts he needed, such as a Richmond Super T10 gearbox and bellhousing, a spare set of race-only wheels, a new 600cfm Holley carb, and plenty more.

“By this stage, the car’s performance was improving, and a new term had slipped into my vocabulary — in response to my wife’s questioning about the cost of the new parts. ‘A couple o’ hundy’ was generally my reply. It rolls off the tongue well if said fast enough!” Peter recalls, knowing he was pushing his limits with every purchase.

With the bills adding up, a six-cylinder VK that Peter had sitting in the garage was robbed of plenty of parts for the build, including headlights, fuel tank, and window winders. These weren’t added as a matter of necessity, but more in the quest for reliable usability and to make the car as tidy as possible.

Usability for what, exactly? Well, whatever Peter wants really. The car gets used to drive to the shops as often as it does for sealed sprints, the odd fun track day, and hill-climb events.

“So far it has proved very reliable, as we have driven it to, and competed in, motorsport events such as hill climbs and street sprints in Whangarei, Taranaki, Wellington, and Rotorua,” Peter states proudly.

More importantly, not only was the car driven to these events, it was driven home intact. The journeys haven’t been completely drama free, though, with two ‘I wish I’d bought a trailer’ experiences along the way. The first was a wobbly rear wheel, after a tarseal autocross event. It turned out to be caused by a rear axle that had been broken and welded back together at some stage in the car’s history. The second interesting drive home was with a badly slipping clutch after a day competing in the Commodore Car Club Sprint Series at Pukekohe Park Raceway. As we all know, though, experiences such as these — as painful as they may be at the time — make for great memories afterwards.

With the car now running trouble free, Peter’s keen to give others the fun that it can offer, by slapping a magnetic ‘Taxi’ sign on the roof when at the racetrack and thrilling as many passengers as he can.

“Big burnouts off the start line and sideways cornering ensure that fun is a key factor, accompanied with the symphony of a screaming 327 small block,” he declares.

These days, it’s not just track duties the car gets used for, as Peter has recently purchased a car trailer. Don’t go thinking for a minute that the VK goes on the trailer. Rather, the VK has become the tow car for Peter’s latest purchase, a rotary-powered Chevron sports car, which Peter also uses for track day types of events.

So, how much do you think Peter’s spent over the years to buy, build, maintain, and complete the all-round package? How does just shy of $20,000 sound? Makes you think, doesn’t it!

1986 VK Holden Commodore

- Engine: 327ci small-block Chev, ‘fuelie’ heads, Holley 600cfm carb, Weiand inlet manifold, Holley Blue electric fuel pump, Holley fuel pressure regulator, HEI ignition, MSD rev limiter, Flowmaster-style muffler, single side-exit exhaust, custom alloy radiator, thermo fan

- Driveline: Richmond Super T-10 close-ratio four-speed, with Hurst shifter, Xtreme 10½-inch chromoly flywheel, Xtreme ceramic clutch, TIlton hydraulic release bearing, BorgWarner diff, 3:23:1 LSD, heavy-duty two-piece driveshaft

- Suspension: adjustable coilovers (camber, castor, height adjustable), Bilstein shocks, Eibach springs, 27mm front sway bar, adjustable Panhard rod, adjustable upper trailing arms, Nolathane bushes

- Brakes: standard pedal box, one-inch master cylinder, Jaguar four-piston front calipers, 330mm front rotors, Holden rear calipers, 277mm rear rotors, EBC Yellowstuff brake pads

- Wheels/Tyres: 17×8-inch ROH RT, 235/45R17 tyres

- Exterior: Group A front air dam, Group A boot spoiler

- Chassis: Castlemaine Rod Shop (CRS) Chev-to-Commodore installation kit, seam-welded floorpan and chassis

- Interior: Momo race seats, full harness belts, Momo steering wheel, Hurst shifter, Auto Meter gauges, six-point roll cage, carbon-fibre door cards

- Performance: 253hp (at the wheels)

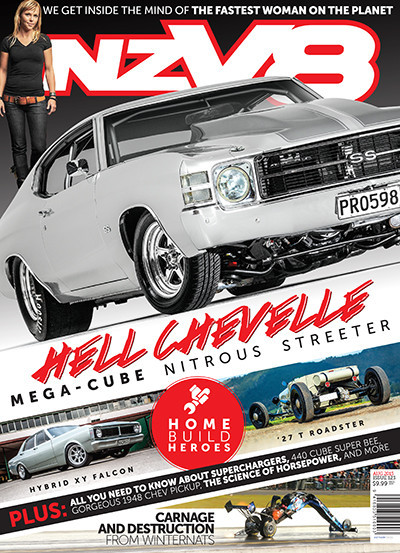

This article was originally published in NZV8 Issue No. 123. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: