data-animation-override>

“Wade Nisbet wanted to build himself a simple and cheap hot rod. Nine years later, he emerged from the shed with one of the most complex home builds you’ll ever lay eyes on!”

“I don’t go in for spending a fortune on name-brand parts for the car. Mainly, I can’t afford the coin to do that so I modify something to make it work, or just make it, full stop.”

That simple statement sums up the build of Wade Nisbet’s ’27 Model T roadster perfectly. Some of us claim that, since we bolted together some parts we bought, and outsourced the hard bits, we’ve built a car. When you chat to Wade about the lengths he’s gone to in building his car, though, you’ll soon end up feeling not only embarrassed about how little you did but pretty damn useless, too.

Wade’s dream of building himself an open-wheeled, open-top cruiser was inspired by cars he saw competing at a hill climb many years ago. Originally, the plan included using a Ford Kent cross-flow four-cylinder motor, but the more he told people of the idea, the more they suggested he’d regret it, and that V8 power was the way to go. With this reality setting in, he turned instead to a motor he’d stored away in the shed for another project.

Wade began the build by placing the 215ci Buick motor onto a chassis table he’d secured from the old Ford factory in Wiri many years earlier, along with a diff and front end he’d picked up from the Pukekohe Swap Meet for $150 apiece. The ’27 roadster body he’d ordered from Te Puke — asking for the unneeded turtle deck to be cut off — soon arrived and was added to the pile of parts.

“Taking measurements from the Mk1 Escort I was driving at the time, I laid things out in a similar fashion. Distance from the seat to the column, brakes, firewall, etc. determined where the firewall would sit. I found that room for my feet was going to be somewhat restricted, so decided to widen the body at the cowl by about 100mm. This meant that the normally bent rails of a Model T would now be straight full length, which made life a bit easier, and gave me more room for my feet. I also decided to move the engine and gearbox forward to put the torque converter in the engine bay, not set back into the tunnel. This added more room for feet, but pushed the wheelbase out further,” Wade says of the early stages of the build.

Of course, getting it all as low as possible, yet still retaining comfort, did end up seeing the wheelbase get extended even further from the original proportions Wade had planned out. As he explains, “The next restriction was the front of the engine at the water pump. I was not going to be able to use a fan driven off the water pump, so an electric fan was used. This set the positioning for the radiator, which determined where the front of the chassis would be.

Once I knew where the chassis would finish, I could sort out how to work the torsion bars and where the front axle would end up. All of this added up to a minimum length into which I could fit everything. A 120-inch wheelbase was the final tally — that’s 10 feet! It’s very long, but would work in well with the wish to have a car that belonged on the salt running straight.”

With everything sitting in position, a wooden frame was created; once Wade was happy with it, it was replaced with steel. All up, there’s more than 40 metres of 1¼-inch boiler tube in the custom chassis, all of which Wade bent, cut, and welded himself, each join being hand filed to perfection before welding could take place.

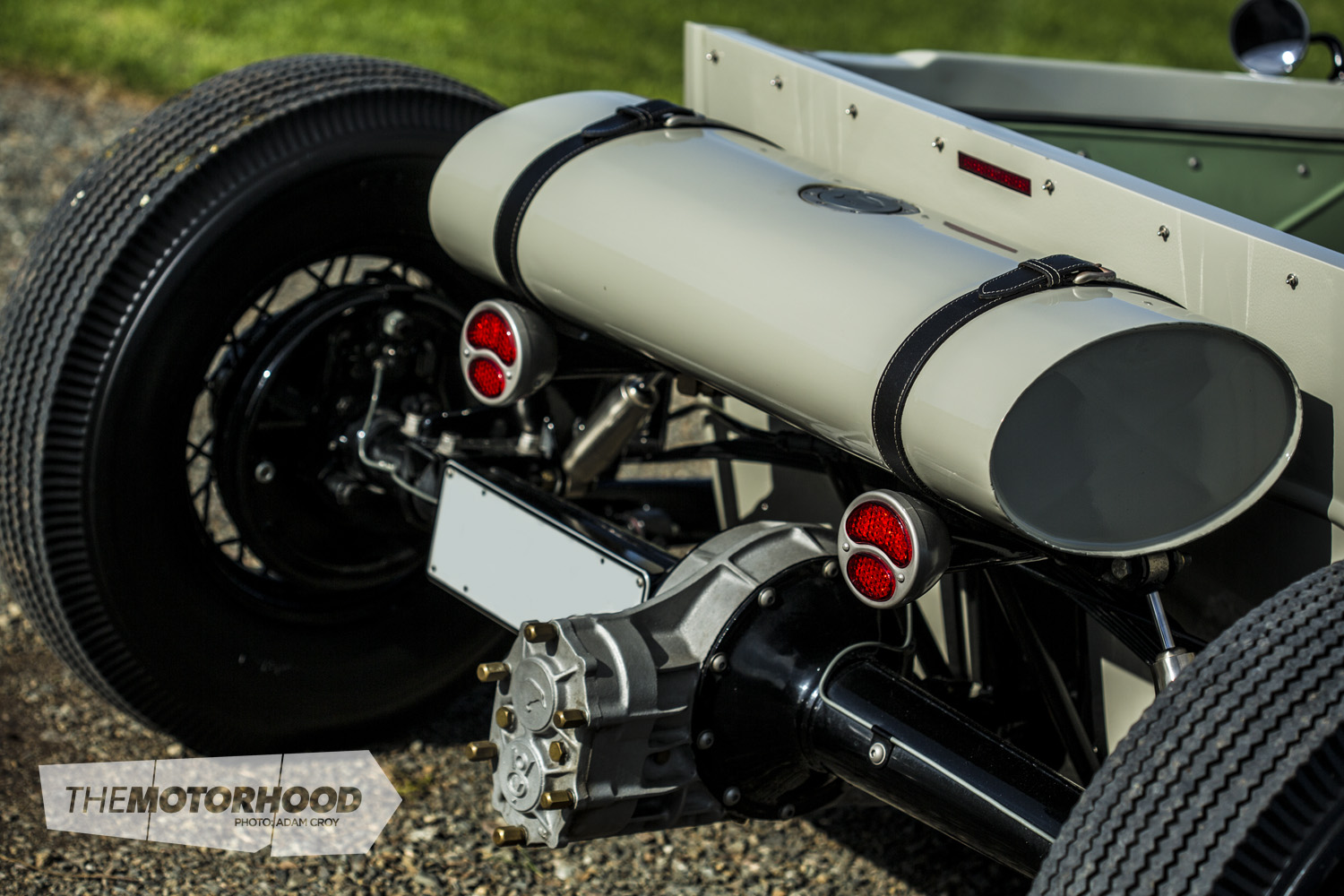

Grafted into the custom chassis is a complex suspension system relying on torsion bars up front and a transverse leaf spring on the rear. A ’46 Ford axle was fitted with split wishbones, but it’s the handmade — by Wade — spherical knuckle joints that take things to the next level. With Wade thinking outside the box, the right-hand side uses a single joint to act as a Panhard, while on the left-hand side are double knuckles, allowing the arms to swing through opposing arcs.

Out the back, that transverse leaf, originally fitted to the front axle, has had its eyes reversed, and is fitted to custom-made perch mounts, along with a custom Panhard bar and trailing arms. The same tubing that was used for the chassis was also used to create these arms, which Wade cleverly bent up to match the lines of the body, such was his attention to both design and aesthetics.

With the heavy fabrication side sorted, Wade turned his attention to the body. He used no fewer than five full sheets of panel steel to create it. The firewall came first, hammer formed, swaged, and bent, before being cut to fit around the chassis tubing. Wade’s desire to have a matte finish saw the stainless fasteners he used to mount the body to the frame bead blasted and clear coated before being fitted. Talk about making things time consuming for yourself!

The process of panelling out the body consisted of cutting patterns in 3mm cardboard.

As Wade mentions, “It’s much easier to fix card with tape and scissors than it is to fix steel!” These patterns were then transferred to panel steel — and, such was the accuracy of the process, Wade never had to remake any. Each panel was treated to a layer of sound dampening to help stop any potential rattles, before being painted.

Right from the beginning, Wade knew that his seating position within the car was critical, as he didn’t want to be sitting up high, nor have his knees around his ears; more importantly, he wanted to be comfortable.

“To achieve this, I put the seats on the floor, and have only a two-inch squab cushion on them. They turned out really comfortable, even without padding on the back. Once in the car, you can’t slide around, so you feel very protected, and stay pretty dry so long as you keep moving!” he says.

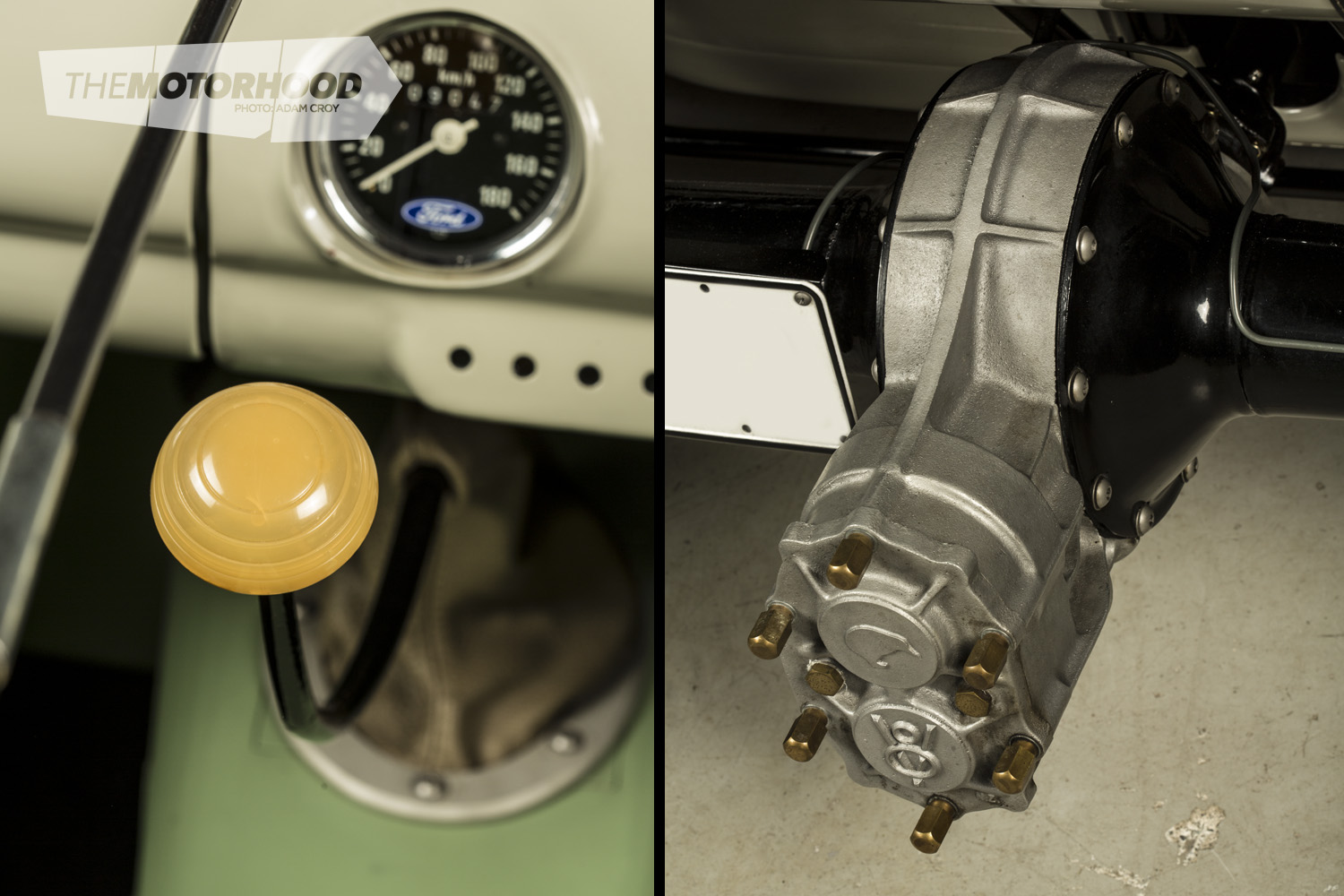

Like those seats — made from panel steel — the rest of the minimalist interior was crafted by Wade himself. The dash is a narrowed and sectioned item from a ’46 Ford, and is now fitted with a gauge that was purchased from a swap meet and refurbished. The glovebox does work, but, with the battery behind it, there’s not all that much room inside.

The shifter and steering wheel are perfect examples of just how far Wade was willing to go to get things how he wanted them, and also a great sign of his talent. That seemingly stock steering wheel was actually hand made, starting with a piece of metal that Wade found in a scrap pile. After machining it to his requirements, he used an offcut of puriri he got from his dad to make the wooden rim. While that sounds complex, he assures us that it was easy compared with the three-week process involved in making the shifter, which started life attached to a 1939 Ford manual gearbox. During the build, he incorporated a custom reverse lockout to ensure that the odd shift pattern (PNDLR) of the Buick Dynaflow transmission didn’t accidentally see him knock it into reverse while on the move.

Speaking of making things work, the steering column in the car is another of Wade’s own creations. Sure, the shaft inside is from a British Ford Escort but the rest is a pure rural Whangarei creation.

When it came time to wire up the car, Wade again took care of the task himself, with a bit of guidance when required. Wanting minimal switches inside the car had its hurdles, but ones that were overcome with a bit of clever thinking. Nowhere is that more obvious than with the indicator switch arrangement.

“It runs off a sealed electronic unit that actuates the indicators and cancels them after seven seconds — unless the brakes are used; in that case, it counts to seven after the brakes have been let off. No more driving down the road with the indicators on for 20 minutes!” Wade laughs.

The warning lights in the dash have cleverly been hidden behind the dash’s factory switch panel, and created from bits of perspex in appropriate colours. Again, it’s a mix of forward planning, attention to detail, and minimalism. The colour used on the interior is a nod to the naval planes of the ’40s and ’50s, and ties in with the whole concept of the car being along the lines of what a returning serviceman would have built back in those days.

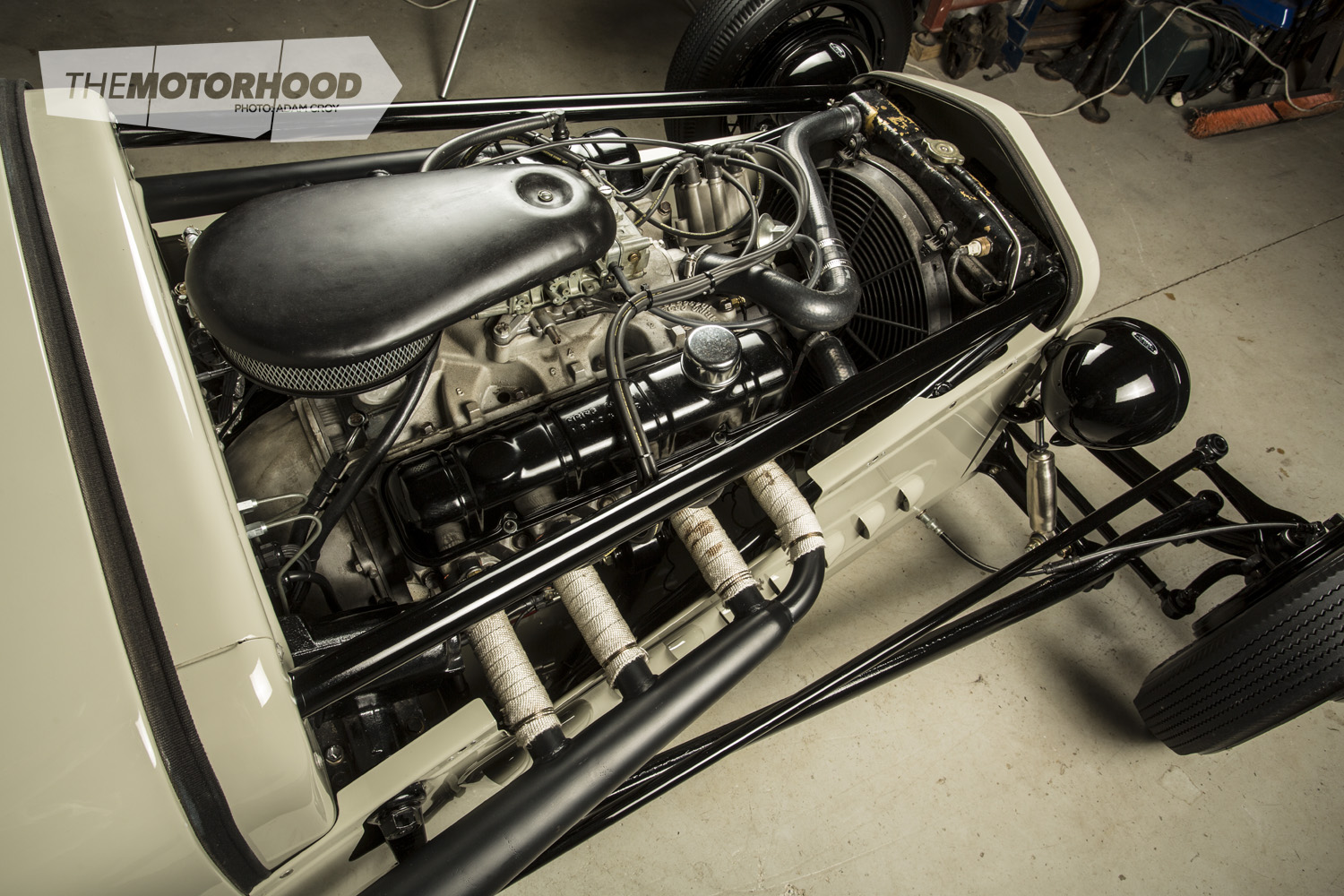

The exception to that period-correct thinking is the motor, which Wade essentially rebuilt to stock specs — apart from the slightly wilder camshaft. Being a rare motor, it wasn’t easy to get parts for, hence Rover pistons being used in its build. The difficulty of sorting those was minimal compared with the intake set-up, though, as Wade tried at all costs to ensure nothing protruded through the long and low bonnet.

“I found a four barrel intake at the Pomona Swap Meet in 1994, which we had to build up around the thermostat housing with a bit of alloy welding and machining due to some corrosion issues. The intake was originally set up for a Rochester carb. There are adapters available to bolt on a Holley, but I couldn’t afford the height of those under the hood, so I set about drilling out the new [Holley] bolt position oversize into the manifold. Into these holes were welded slugs of alloy and then it was milled flat, drilled, and tapped to Holley specs.” And, just like that, Wade had a manifold that could take the 465cfm Holley carb he had lying around.

The next difficulty, though, was making a filter assembly that would fit below the hood. For this, Wade spent plenty of time wheeling and hammering a piece of panel steel into the work of art you now see before you.

The Dynaflow trans was given a rebuild by the team at Advanced Automatics Northland, and a driveshaft created by Henwood Automotive to attach to the Kiwi Quickchange diff out the back. That diff is identical to the one used by Bill Ward on his Kiwi A Salt car at Bonneville, which is a bit of added inspiration for Wade, who’d love to take the car over there one day — not for racing but to enjoy the drive from San Diego to the salt and back.

For now, since the car’s completion, Wade has been out clocking up plenty of miles. The fact that the car’s got no boot or luggage space at all, apart from the passenger seat, hasn’t stopped him from touring around the North Island. On his trip to the Pre ’49s in the Wairarapa last year, Wade left with a tent and toolbox beside him, and managed to stop in at Kumeu, Whitford, Hamilton, Mangakino, Taupo, Napier, Palmerston North, Masterton, Cape Palliser, Paraparaumu, Wanganui, Hawera, Cape Egmont, and New Plymouth before driving home again, all in the space of 10 days.

While the thrill of driving your own creation will never be experienced by most of us, Wade also fondly remembers the trip for the people he met and the friends he made along the way. Since then, the odometer has continued to climb.

What is Wade doing with his time now that his work of art is completed? He’s turned his attention to building a ’39 Ford coupe. Having seen what he can build when starting with a motor and a pile of tubing, we can’t wait to see what he can create when he starts with an actual car! We have no doubt the project will be another long one, but we also have no doubt that the outcome will be amazing.

[Breakout Box]

Build thread

Wade’s managed to document the entire build of the car, and, if you’ve got a few hours to kill, it’s certainly worth a look. You can find it over at jalopyjournal.com — aka the H.A.M.B; search for the user name Woodbox. The workmanship and detail on the car are so great that we can really fit only a brief overview of it on these pages, so the build thread is well worth a look.

1927 Model T Ford Lakes modified roadster

- Engine: 215ci Buick aluminium V8, 30-thou overbore, Rover pistons, custom cam, forged steel crank, converted to lip rear seal, stock valves, hardened valve seats, new guide seals, uprated springs, modified four barrel manifold, 465cfm vacuum secondary Holley carb, custom intake ducting, custom 45-litre fuel tank, Holley Red fuel pump, stock distributor, custom internally baffled headers, Toyota radiator, electric fan

- Driveline: Buick dual path Dynaflow transmission, 1946 Ford pickup diff, Kiwi Quickchange centre

- Suspension: 1946 Ford axle, split wishbones, torsion bars, Speedway Motors shocks, custom spherical joint knuckle attachments, transverse leaf rear spring, custom perch mounts, custom Panhard bar, custom arms

- Brakes: custom pedal box, Wilwood tandem remote master cylinder, custom stainless steel reservoir, Wilwood proportioning valve, 12×2-inch drum brakes

- Wheels/Tyres: 16×4-inch and 16×6-inch 1936 Ford V8 Wires, Firestone bias ply tyres

- Exterior: widened fibreglass body, functional cowl vent, custom grille surround, hood sides, belly pans, firewall, sill panels, rear body, etc.,PPG paint

- Chassis: scratch built from 38mm OD 3.8mm wall boiler tube

- Interior: custom bomber-style seats, custom aluminium steering wheel, quick release hub, custom steering column, Ford Escort steering shaft, modified 1939 Ford manual gearbox shifter, swap meet gauges, custom indicator electronics, narrowed 1946 Ford dash, 1950s Morris Minor handbrake

- Performance: built to cruise

This article was originally published in NZV8 Issue No. 123. You can buy a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: