data-animation-override>

“From dirt tracks to drag strips, this old coupe has done it all!”

Bob Owens’ 1934 Ford coupe will be no stranger to most of you. After all, this really is one of New Zealand’s most iconic hot rods, well known for both its great looks and its stellar performance over the years. It’s one of those cars that seems to have been on the road forever, which is not surprising, as it’s been 30 years since Bob’s car first hit the road in anger and anyone who knows it knows that it can get really angry at times! In an age of reproductions and replicas, it is great to see an old steel coupe on the roads — although there are a few American imports around now. What makes this coupe even more amazing is that it is a New Zealand–new factory right-hand drive, which makes it a real rarity, and its life prior to Bob’s ownership makes its survival even more incredible.

Back in the early ’80s, Bob and wife Wendy were clocking up the miles in a nice 1932 roadster and putting plenty of high-speed passes down the strip, too. While they loved the car, the novelty of its lack of a roof soon wore thin; after a few too many soakings, the couple decided to build another car — one with a roof. Back in the days before the internet — not that Bob knows how to use it — Auto Trader, Trade & Exchange, and other magazines and newspapers were the only search engines available, and, in 1984, Bob spotted a 1934 coupe for sale. There were actually two for sale at the time — one in Hawke’s Bay selling for NZ$4500, and one reasonably local being sold by John Allen for NZ$2500. Bob checked out the latter; although it was pretty rough and rusty, it was all there. After a bit of haggling, Bob dragged the old Ford home.

The coupe had already been chopped by 2½ inches and had race numbers on the side, which suggested it had been raced somewhere at some time in its past, but neither Bob nor John knew its history. Well-known hot rodder Gary Pulley helped fill in the blanks, as it was he who had chopped the car and painted it many years earlier. As it turns out, the coupe had been a stock car and was raced at the Forest Lake track — hence the numbers on the doors. Thankfully, the doors hadn’t been welded shut back in the day, as there was already plenty of work ahead for Bob, repairing 50 years of abuse and neglect.

Starting at the bottom, Bob put the old Ford on its roof — and has photos to prove it — to repair the floor, before putting the coupe the right way up, filling the roof, and then tackling everything in between. The rear inner guards were carefully removed, and, as Bob crafted the tubs, the factory steel work was put back in, so the car looks stock — albeit seriously inset!

Bob worked on the coupe every evening for 12 months, removing the rot, smoothing out the dents, and getting it into the condition he wanted before handing it over to a chap called ‘Haggis’ for final prep and a custom blend of red.

The coupe was never going to be a street rod — it was going to be a proper hot rod with power to burn — so, once the body was sorted, Bob needed to build a suitable chassis to put it on. An Osborne chassis was sourced, which Bob then braced and tweaked, as he wanted something significantly stronger and far more rigid than Henry’s original offering. A six-point cage was also added to further stiffen things up.

A Vauxhall Victor 3.3 donated its front end to the cause, giving both the handling benefits of an independent front end — rather than a beam axle — and disc brakes. Bob built a four-bar for the rear, utilizing Jag coilovers to keep the Ford nine-inch diff located and under control. A set of 31-spline axles, an LSD head, and 3.7:1 gears were also chosen, with Bob thinking the ratio should give a good compromise for street and strip use.

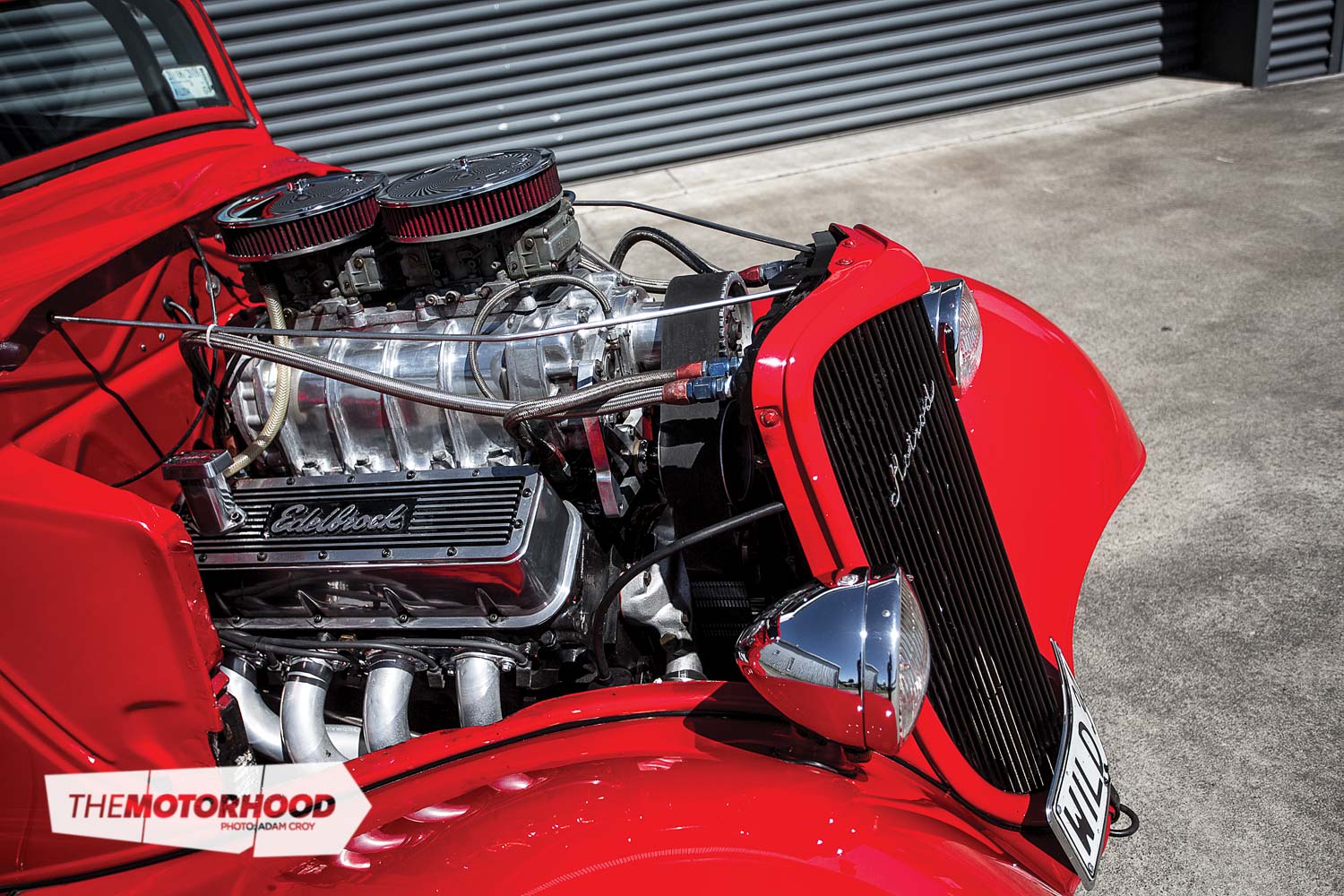

The plan was to build a hot rod on steroids — something wild and on the edge of being streetable — and Bob knew just how to go about it. While he was building the coupe, his good friend Chris Tynan was having a lot of fun in his wild ’55 Chev, which Bob had been doing a bit of work on. Bob decided he’d have a go at Wild Bunch with the coupe, too. Tynan built the engine, based on his experience with his own Chev. A GM 427 four-bolt block was stuffed full of all the goodies of the day, and topped off with a set of modified oval port heads, and a 6-71 blower and injection. The combo was backed up by a race-prepped Powerglide built to take the punishment.

An engine like this needs to breathe, so Bob built a set of headers to match the Tynan-ported heads, with primary pipes so big that there is almost no surface area left for a gasket. These lead into four-inch collectors and a twin four-inch exhaust exiting in front of the rear wheels.

With the chassis sorted and the body on, Bob plumbed in the Holley Blue fuel pump, wired the MSD, and, before long, the coupe was ready to go — just not straight! The first time Bob drove it, he didn’t want to get back in again, convinced there was something wrong underneath that he had missed. It was just too wild, with a real bark to the engine that, even a few decades later, his current race car can’t match. The coupe just wanted to stand up on its tail and go where it wanted — which was generally never where Bob had pointed it.

Anyone who frequented Thunderpark in the late ’80s will have memories of the out-of-control coupe that just couldn’t take the horsepower Chris and Bob had built for it. Bob just couldn’t get into it, as a slight stab at the throttle saw it doing wheel stands, rubbing the guard rail, or both, as it weaved from one side of the track to the other — every pass was a wild ride. Some would say there is such a thing as too much power, but Bob thought he just needed to figure out how to drive the car!

At one meeting, Bob had the coupe launching hard trying for a good ET, wheel standing hard off the line, and, every time he looked like touching the gas, the coupe would swing violently from side to side, popping wheelies all the way down the track. It turned out that the result of the hard launch was not a quick ET but that all the four-bars got bent. A quick trip to a local engineer saw the bars straightened and a length of tubing pressed over each four-bar before it got welded in place. Sure, it may take both hands to lift each one, now that they are effectively ¼-inch wall (thickness) bars, but Bob was back at the track the next day and they haven’t bent since.

Bob persisted at the strip for a couple of years, but no matter what he did, the old coupe just couldn’t get the power down. Even so, Bob managed a best pass, at only part throttle, of 9.40 at 150mph. Some of his best passes were when the Powerglide failed and lost first gear. With no option other than to launch in top gear, the car ran straight to a series of 9.60s at 150mph.

At another meeting at Thunderpark, it lost top gear and Bob ran a series of wild passes at 10.0 at 110mph, running through the traps at 9500rpm in first. Chris obviously built the engine well, as it regularly saw 9500rpm, and it’s still intact today, albeit slightly detuned. Bob had wanted to get the coupe into the eights while it was still being street driven, but it was just too wild and would need cutting up and turning into a dedicated race car to do it. The horsepower was certainly there, as was proved when the engine was fitted to the XM Falcon Bob built next, and it ran an off-the-trailer 8.70 at 167mph — it just had more power than the ’34 could take.

When a new engine was built for the XM, the coupe’s 427 injection was swapped for twin 660cfm carbs and refitted ready for some street miles.

Bob always says hot rods are for driving not trailering, and he is not afraid to get out there and drive it — even though there have been a couple of issues over the years. On one trip to Auckland, one of the roller lifters seized in the block. Apparently, solid rollers for race cams of over 0.800-inch lift don’t have oil grooves for lubrication — something Bob was yet to learn. It packed up as Bob went over the Bombays, jamming the intake valve open and the resulting backfire through the blower cracked the back plate, seizing the blower. Undaunted, Bob dropped off the blower belt, pulled the spark-plug lead for the damaged cylinder, and started it up again. Sure, it idled high due to the vacuum leaks through the back of the blower, but Bob figured it ran well enough to keep driving it. Doing a U-turn across the grass strip on the motorway — no barriers back then — the coupe headed back home on seven cylinders. The cam was pulled and the seized lifter hammered out, before Bob fitted a new LS7 cam and lifters he had in the shed. He then welded up the cracked blower, fitted a second-hand valve to the head, and he was back driving the next weekend.

There have been a few other concessions to streetability over the years, none of which has diminished the sheer awesomeness of the coupe. Bob had stayed with the big roller camshaft, as the 427 was running pop-up pistons for racing, and with 10.0:1 compression and the blower, the big cam helped keep the cylinder pressures down, helping with running on the street on pump gas. Following a cam change, the engine was upsized to 454 cubes, using some proper blower pistons and the old BRC race crank out of the Falcon, which improved the coupe’s street performance. To further improve drivability, the Powerglide was swapped out for a modified TH350 with a more sensible 2500rpm stall converter, which has stood up to the 750-plus horsepower without issue. The extra gear more than compensates for the lower stall speed and makes the coupe much easier to drive.

Other modifications have come through necessity — such as increasing the number of bolts that hold the bottom blower pulley on from three to six after the bolts sheared off.

Reflecting on 30 years of driving ‘WILD34’, Bob has nothing but praise for it. While a few blemishes are starting to show, it still scrubs up well and the car has more than fulfilled Bob’s desire to build a hot rod on the edge of drivability. This is a car that pulls people in — at any hot rod event, there will be people hanging around the car, and, as soon as it is fired up, people start grinning. It’s one of those cars that people love — not to mention that, nearly three full decades after it was first built, it is still one of the fastest hot rods on the road!

1934 Ford coupe

- Engine: 454ci big block Chev, GM 427 four-bolt block, steel crank, Ross pistons, GM rods, mild flat-tappet cam, modified oval port heads, 6-71 blower, 12-per-cent overdriven, twin 660cfm centre-squirter carbs

- Driveline: GM TH350 transmission, shift kit, 2500rpm converter, Ford nine-inch diff, 3.7:1 ratio, Positraction head, 31-spline axles

- Suspension: Vauxhall Victor 3.3 front end, parallel four-bar rear, Jaguar coilovers

- Brakes: Ford Zephyr discs front, Ford drums rear

- Wheels/Tyres: 15×5- and 15×14-inch Weld wheels, 165x50R15 Michelin front tyres, 31×18.5×15 M/T rear tyres

- Exterior: Custom red paint

- Interior: Autosport seats, six-point roll cage, Ford Zephyr MkIV gauges, owner-built steering column, Ford shifter

- Performance: Still too much!

Driver profile

- Owner: Bob Owens

- Age: 57

- Occupation: Maintenance engineer

- Previously owned cars: 1932 Ford roadster, 1967 Ford Mustang big block, Ford Falcon XM coupe, Ford Falcon XP coupe, Ford Pop; currently own a 1965 Mustang fastback, ’68 Monaro big block, Ford Falcon XM coupe top doorslammer, and a T-bucket project

- Dream car: 1968–’70 Hemi Cuda — I should have bought one while they were still cheap!

- Why the ’34? I got sick of getting rained on in the roadster!

- Build time: Two years

- Length of ownership: 30 years

- Bob thanks: Haggis for the paint job that still looks great, despite 30 years of use on the road and strip and unexpected abuse, such as having methanol spilt and sprayed on it

This article originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of NZV8. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: