data-animation-override>

“Ken Block’s monster four-wheel-drive Nascar-powered ‘Hoonicorn’ Mustang was designed to blow up the internet, and little do most people know, a team of Kiwis was instrumental in its build”

If you’re reading this then chances are you have watched one, or more likely all seven, of Ken Block’s Gymkhana videos, which year on year over the past seven years have exploded YouTube upon their release. Each video took another step further into insanity, but none more so than the latest and, in our minds, greatest Gymkhana 7.

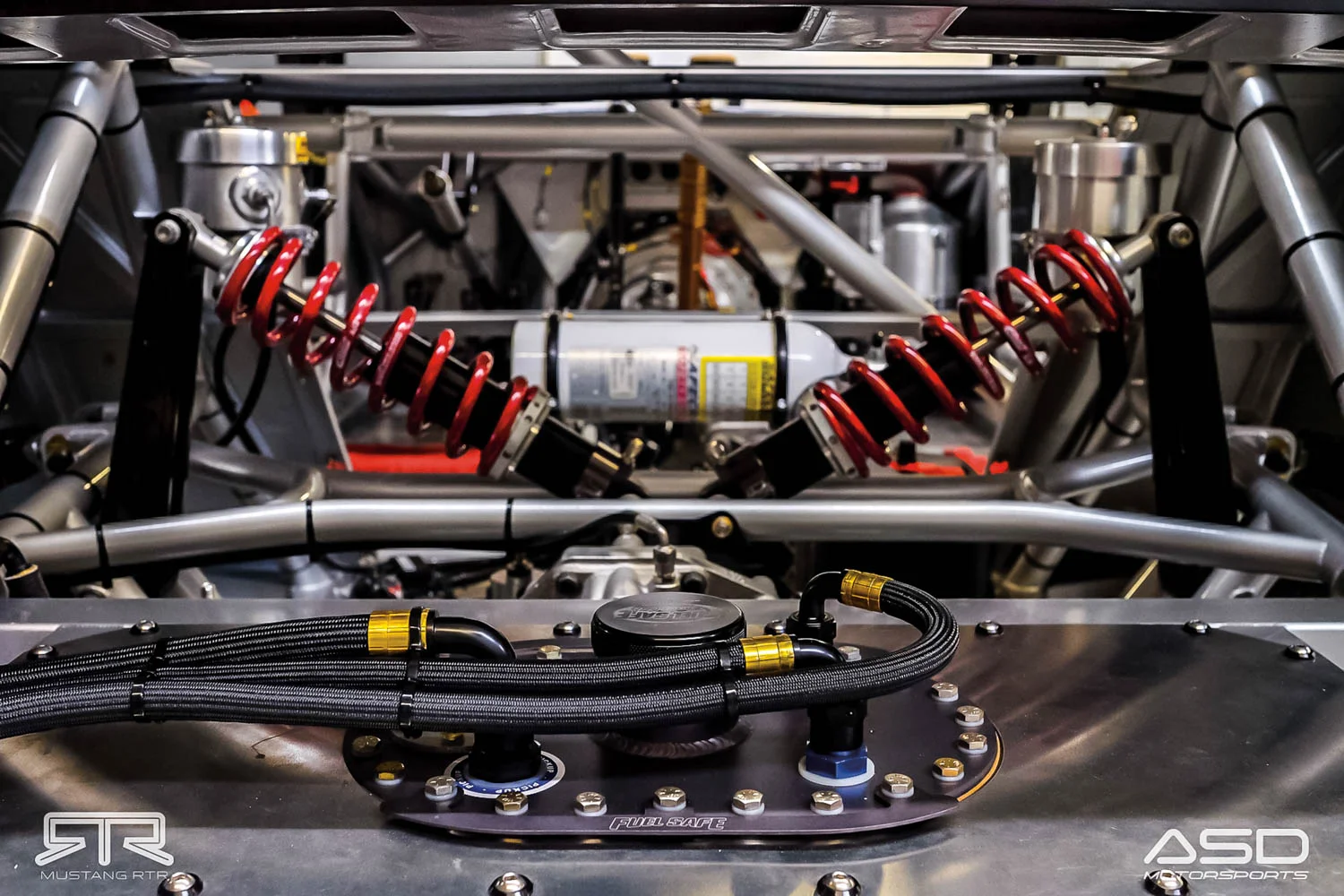

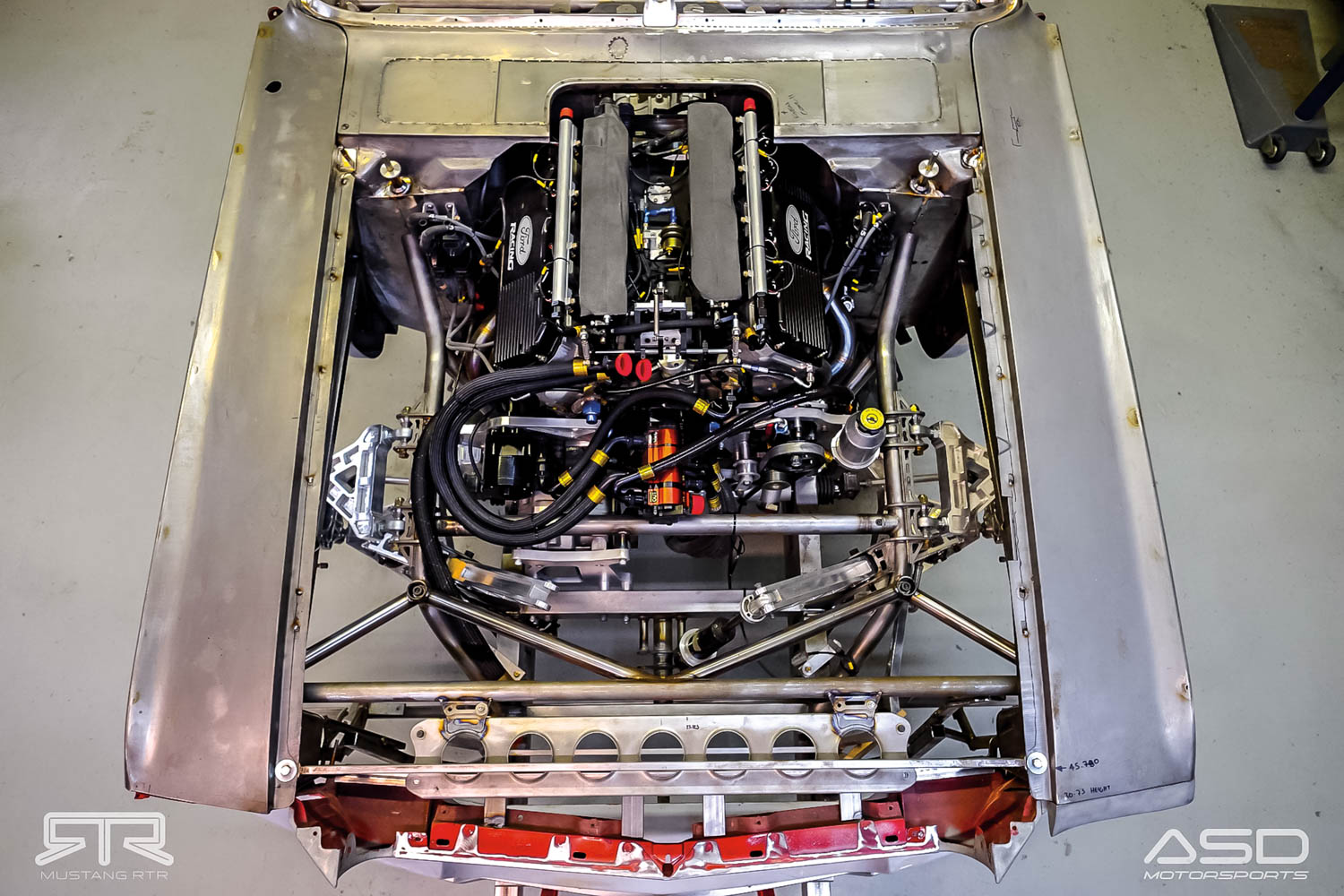

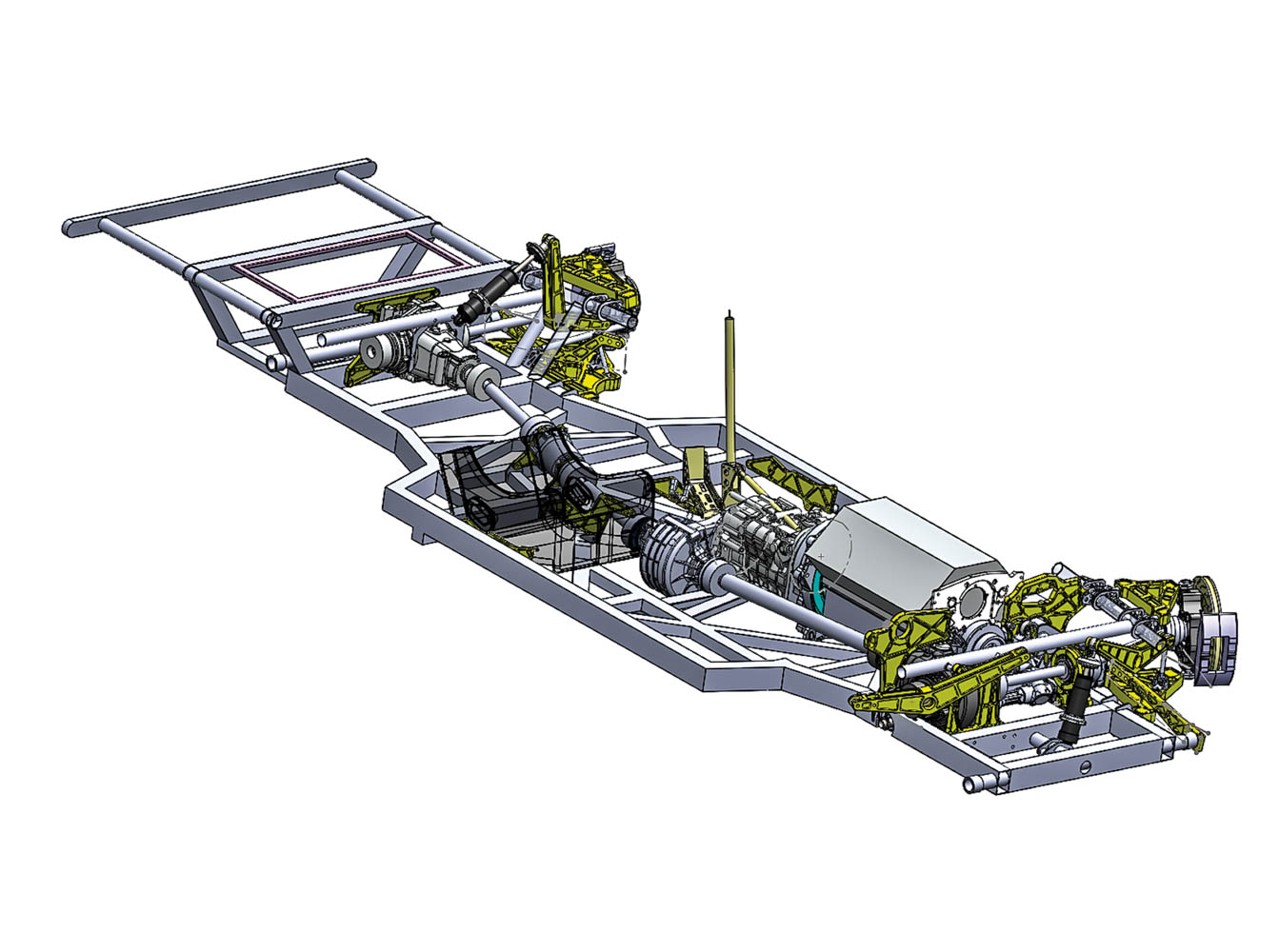

Exactly why we think it’s the best video to date comes down to the hardware. Sure, the Subarus and Fords used in the first six were awesome-performing machines, but Ken’s 1965 Ford Mustang — dubbed the Hoonicorn — stole the show, basically because no one expected Ken to build an all-wheel-drive tube-framed Ford Mustang powered by a 630kW, 6.7-litre (845hp, 410ci) Roush Yates V8, breathing through a Kinsler eight-stack ITB system, and putting power to all four fifteen52 wheels through a bespoke Sadev sequential six-speed all-wheel-drive gearbox, just to burn some tyres. Then there’s the stance — looking as extreme as it does, how could it not become the most talked about car of 2014? You either love it or hate it — there’s no middle ground.

It is now widely known that the Hoonicorn was built by North Carolina–based ASD Motorsports, but what is relatively unknown is New Zealand’s connection with the car via a couple of blokes from Christchurch.

As some of you may be aware, ex-pat Kiwi Ian Stewart is the man behind the hugely successful ASD Motorsports company, and he was commissioned by Ken Block to build the car that would become the Hoonicorn. Jason Burke is the director and master fabricator at Christchurch-based Burke’s Metalworks. He was specifically chosen by Ian as the man for the job of transforming sketches and CAD renderings into something tangible.

We talked to both Ian and Jason to get some info on the build, and to find out how these Christchurch boys got involved in constructing the most polarizing car of 2014.

Autosport dynamics

Before we can get to ASD’s involvement with the Hoonicorn, we need to start with ASD. Ian grew up in Christchurch, and has been fascinated with racing since he was a kid. His dad was friends with many of the guys who raced at the local dirt track, Woodford Glen, and that was where Ian spent most of his Saturday nights when he was growing up. By the age of 16 he’d built his first race car — an off-road buggy. His dad had a repair shop, a small family business, and growing up into that — along with his love of racing — prompted Ian to become an apprentice mechanic in Christchurch’s CBD.

By the age of 22 Ian had flown over to the UK with the intention of getting a job in British Formula 3. At the time the top team was West Surrey Racing, owned by Kiwi Dick Bennetts. Ian found employment as a mechanic at a Ford dealership, and over the next few months convinced Dick to give him a job as a number-two mechanic. From being a number-two mechanic on Mika Hakkinen’s car, Ian was taken on by Dick as a sort of trainee race engineer, working on Christian Fittipaldi’s car.

“It was a kinda bullshit position he created, to be honest with you. He did me a huge favour, and I owe him a lot,” Ian said. It was there he began to learn more about the engineering behind a race car and team.

Ian moved to the US in the early ’90s. He lived in Southern California for around 16 years, and in that time he raced speedway sidecars four nights a week, and began a race fabrication type of business. That evolved into a slightly bigger business building high-end street rods, which is where Ian first met Jason.

“The shop was mostly all Kiwis and Swedes,” Ian said, “so when Jason asked if we had any jobs, I pretty much told him ‘Go on then, get to work!’”

Ian shifted through a few businesses, and was eventually introduced to drifting in 2005 by fellow Kiwi Rhys Millen. ASD was soon started, to run in Formula D — one of the world’s biggest professional drift series — and, with Falken Tire jumping on board, it was all go. Over the following years, ASD rose to the top of Formula D.

The Hoonicorn is born

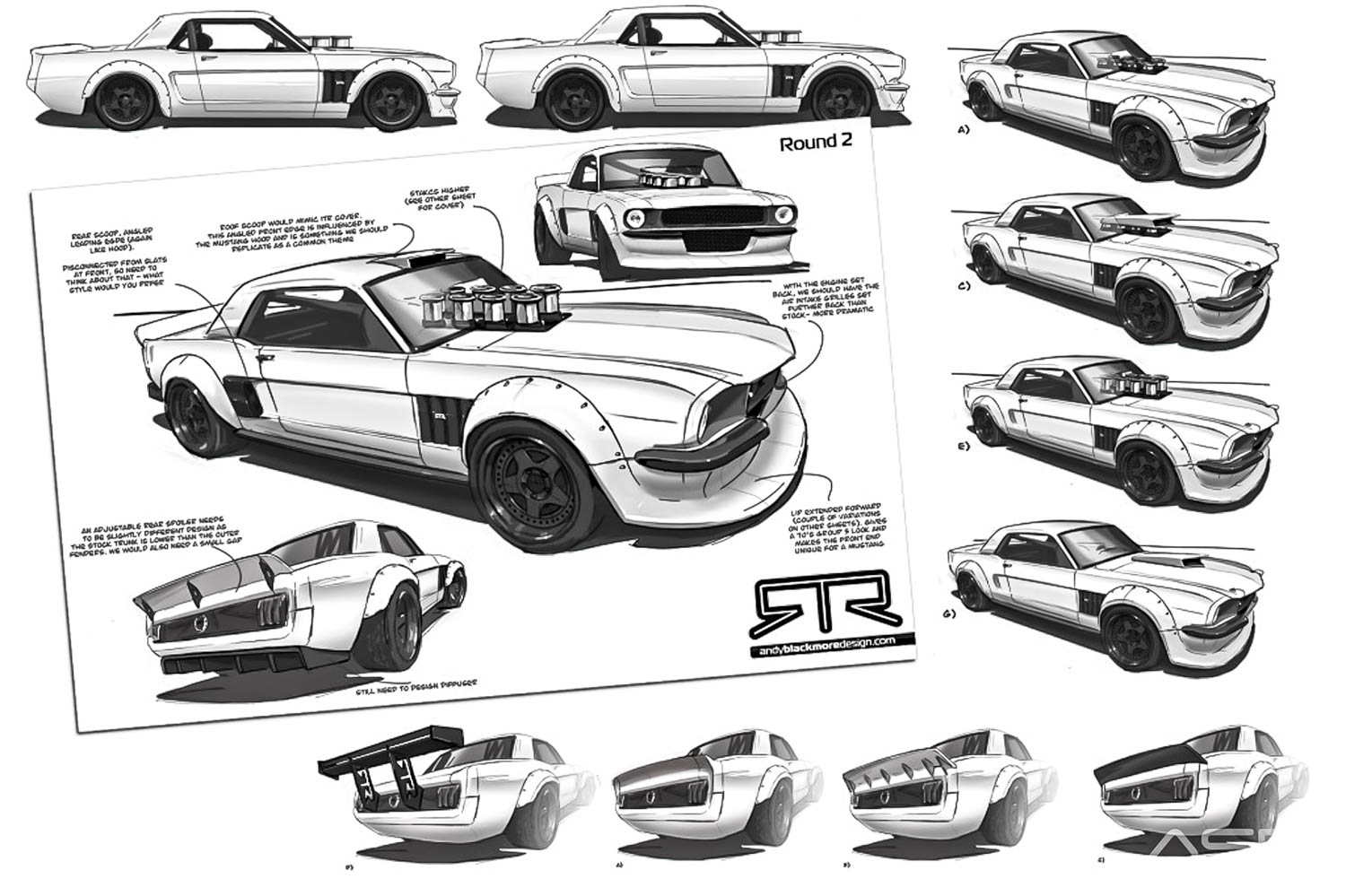

So how did ASD get involved in the Hoonicorn build? Vaughn Gittin Jr is the ASD race team’s professional drifter, the owner of the Mustang RTR brand, and a friend of Ken Block. Ian said, “Ken was at an event in Madrid, and we [ASD] were there with Vaughn. Basically, Vaughn was like, ‘Hey, Ken wants to talk to us about this car he wants to build — let’s go and see if you want to do it’. So we sat in Ken’s motorhome with him and Derek, his right-hand man, and he flushed out this concept — not so much a concept at the time, more of ‘I want a Mustang, and it’s gotta be wild and crazy-looking’. From that point, we made the decision as to what engine, transmission, diffs, and all of that to put into it. We were given this broad concept and left to fill in the blanks.”

Ian jumped onto eBay a few months into the project, thinking it was probably time to find a car. After about half an hour of browsing, he had around 30 Mustangs to choose from. He wanted an ex California car, to reduce the chances of structural rust, and found one that fitted the bill. “I called the guy, bought it over the phone, and one of our race mechanics drove over and brought it back. That was probably the easiest part of the whole build, to be honest.”

During the engineering of the Hoonicorn, all the design work was computer-aided design (CAD) — according to Ian, the car was essentially built in CAD ahead of being physically put together. “It’s the only way that you can guarantee the result that you want and not just end up where you end up. In a project like this, a massive number of man hours and a massive amount of effort and resources are being spent: you can’t end up down a blind tunnel. You’ve got to be so far ahead of what’s actually physically being built.”

Ian was heavily involved in the beginning, up to the point of initial chassis and suspension design and packaging, but once the project was rolling and on the right path, he was able to step back into his normal responsibilities — running the business, race team, and race car. Another Kiwi, Peter Gordon — originally from Christchurch but working at ASD — took over day-to-day project management for the Hoonicorn.

The build takes shape

Ian had to choose who to involve in the project, and it occurred to him that Jason Burke should be at the top of the list.

“For sure, his work impressed me, but when you take on a project, things actually need to happen and you need people with the right approach, work ethic, and attitude. I could have got local guys over here to do the work he did, but I wanted his input and influence as well.”

There are a lot of talented sheet-metal fabricators in North Carolina, from Nascar and the racing industry, but there was another reason Ian wanted to work with Jason.

“I wanted somebody with that hot rod and street rod–inspired influence, someone who understood that, yes, it has a function, but it needs a hot-rod aesthetic and flow as well. That’s something Jason brought — he knows what looks right and what doesn’t,” Ian explained.

Jason was given a call, and asked whether he’d be interested in working on what was, then, a top-secret project. Even so, it was not quite as simple as Jason hopping on a plane and picking up a welding torch — he needed ASD to sort out the Hoonicorn’s wheels first, so he could get the body’s proportions correct. Then there was the task of arranging for the time — with family and business commitments to work around, this was easier said than done. Once he managed to slot it into his schedule, Ian sent him an airline ticket and Jason flew out to North Carolina, staying at Ian’s house and working at ASD’s facility.

“I had to turn my brain off New Zealand and start looking at what they wanted,” Jason said. What does he mean? “In New Zealand, a client may want their Mustang’s guards flared, but the end result is always aesthetically a Mustang. Here, it was the total opposite — the design is tough, raw, and the absolute opposite of the traditional ‘show’ build. The whole look of the Hoonicorn is functional, and everything has a purpose.” For example, the guards were designed with the intention to extract as much of the inevitable tyre smoke as possible, as were the huge vents behind the front wheel arches.

For his role in the build, Jason was given what he terms “kind of free reign” — as long as the Hoonicorn looked like it needed to, he could use whatever dimensions and measurements would get the job done. That said, there was still a design brief to be followed. The Hoonicorn had to look a certain way, and it was Jason’s job to interpret the sketches and ensure that the end result would look correct, whilst maximizing functionality.

Before Jason got into it, the steel boot lid, doors, and front guards of the original, red donor Mustang were installed to make sure everything fitted as it should. Once this was verified, it was go time. Aftermarket steel guards were cut up and modified. The guard extensions were also designed to very exacting criteria — height, width, rolling diameter, and suspension travel all needed to be taken into account. One piece of sheet steel was used to make all four of the overfenders, or guard extensions. A cardboard template was mocked up, and it was only when Jason was satisfied with how the template sat that the steel was cut and wheeled into shape. The deep front valance was also hand formed out of sheet steel, and it fits the car perfectly. Look at how seamlessly it integrates with the nose cone, guards, and overfenders. The planning that Jason put into his work on the car, as well as the level of skill required to actually do it, is just mind-boggling.

The guard extensions are bolt-on units fastened by Dzus clips. In the event of an accident, the flare can be quickly removed and replaced. As with most of the bodywork, the flares are made out of carbon fibre.

“Once the shapes were finalized, the majority of the components that Jason made were used as a plug for making moulds for the carbon. The panels were effectively destroyed in the process,” Ian said.

Though the panels Jason toiled over didn’t even technically see the finished car, there is absolutely no denying how instrumental his work was in finishing the Hoonicorn.

All up, Jason spent eight weeks crafting the Hoonicorn’s bodywork. Let that sink in for a bit — that’s two whole months. Say he worked typical 40-hour weeks, that’s 320 hours in total spent planning, shaping and fabricating bodywork. Somehow we get the impression that he spent a bit more time than that, though. It was a surreal experience, Jason said, and he often found himself hoping it would make it to video — the whole time aware, such was the secrecy surrounding the build, that he was working on an élite car which might not ever see the light of day.

But it wasn’t all work and no play — Jason said that he learned quite a bit from what he saw in the States. Being in North Carolina, he was lucky enough to visit a couple of race shops over a weekend, and got to see in person what the world is doing. Jason considers himself a “decent welder” — a pretty humble statement — but said he saw guys doing work that blew his mind.

“Some of the guys doing fabrication work for Nascar teams are around 18 to 25 years old, but they’re that good, doing welds that you wouldn’t even want to paint over. There are builds and work going on over there that we just don’t see in New Zealand.”

Sounds as though Jason has brought inspiration and a few ideas back home from his stint behind the biggest car of 2014, and we’re looking forward to seeing the results.

Our thanks to Ian Stewart, of ASD Motorsports, and Jason Burke, of Burke’s Metalworks, whose time and help made this article possible.

This article was featured in NZV8 Issue No. 118 (March 2015). You can grab a copy here.